DNA is essential for life. Every cell in our body contains DNA – it’s the set of instructions that tell cells how to behave and what proteins to make. It is also the way in which genetic traits such as eye colour can be passed on to children, and why you have traits from each of your parents.

DNA was first discovered in the 1860s, triggering a century of research that led to researchers discovering the exact shape and structure of DNA in the 1950s.

DNA has a ‘double helix’ shape, with two strands which wrap around each other. In between the strands are pairs of special molecules called bases. The order of these bases is what makes up the genetic code and allows traits to be inherited.

Since then, there has been a never-ending effort to understand exactly how DNA behaves, what each bit means, and how it affects us. For example, we know that DNA errors can cause cancer – but we don’t often know the precise mutations that are causing the problem.

One of the challenges is that the human genome, the complete set of DNA found in our cells, is massive. Almost every cell in your body contains this genome and, if the DNA was stretched out and unravelled fully, it would be two metres long. It’s made up of around 3 billion pairs of special molecules and contains around 25,000 different genes.

Until the past couple of decades, over 98% of this was thought to be ‘junk DNA’ because it did not give instructions for proteins. These bits of non-protein coding DNA can be sandwiched inside genes, separating genes, or even just repeating the same bits of codes over and over for no obvious reason.

Now, researchers know that these non-coding areas have important functions, like regulating which genes are turned on, helping a gene to code for multiple different proteins, or protecting regions of the genome during replication. That means there’s a lot more DNA that needs to be understood, making research into the causes of childhood cancer a lot harder.

Genomic dark matter

Now that the idea of ‘junk DNA’ has fallen out of favour due to the increasing understanding of the usefulness of these areas, researchers are using a new term: ‘genomic dark matter’. This term refers to all of the bits of the genome that we don’t understand, and acknowledges that these areas might have important roles that are yet to be discovered.

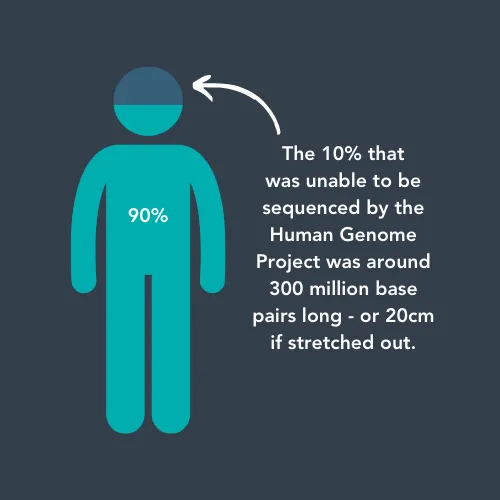

When the first human genome was sequenced in 2003 after 13 years and $2.7 billion, it was not actually fully complete. About 10% of the DNA found in our cells was not sequenced, partly due to the dim view of ‘junk DNA’ and partly because the technology at the time wasn’t good enough to sequence it.

Technology improved to the point where we could read these areas of DNA in 2021, and we now know that some of these repetitive regions help protect and regulate DNA when it is copied as part of cell division. This means that errors in these areas could be important in cancer development.

Understanding centromeres

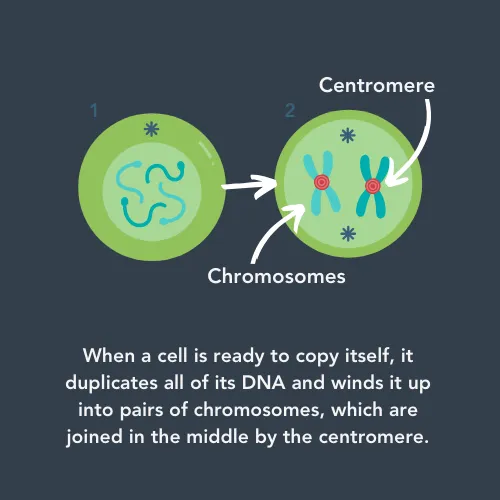

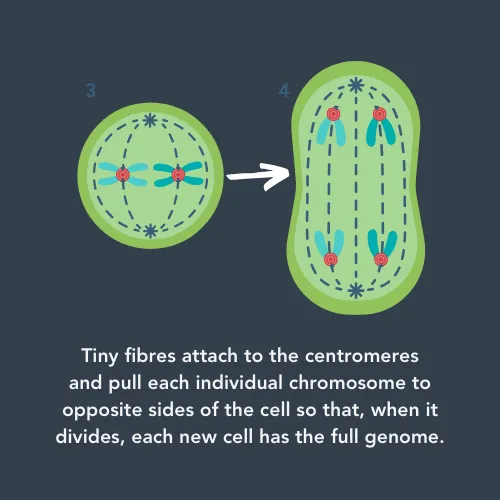

One of these repetitive regions of DNA is called the ‘centromere’. Whilst it doesn’t code for any proteins, it has a vital role in cell division. When cells divide into two new cells, they need to make sure each cell has a copy of the full genome. First, they copy all their DNA, and then wind it up into pairs of chromosomes for safekeeping. These pairs are connected by the centromere, which the cell grabs hold of and uses to pull half of each pair to opposite sides of the cell. This means that, when the cell is split across the middle, each new cell has all the chromosomes.

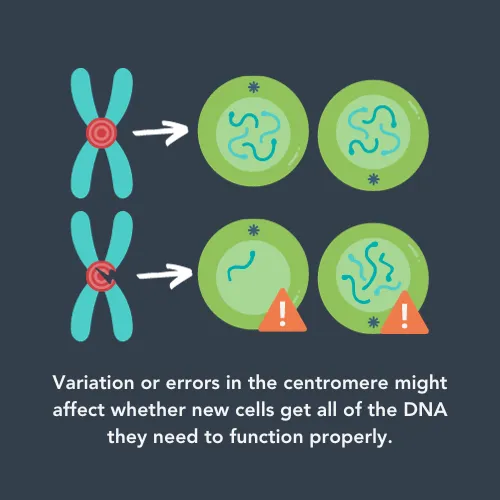

If there are errors in the centromeres, it could affect how much DNA each cell gets. This could lead to the new cells not working properly. For cancer cells, this could affect how aggressive they are or whether they respond to treatment.

Dr Sarra Ryan, based at Newcastle University, is working on a Little Princess Trust funded project to understand how centromere regions differ in childhood cancer cells.

However, whilst technology is now advanced enough to sequence genomic dark matter, it is very expensive and cannot look at differences between people. Therefore, Sarra has had to develop a more efficient way to read the repetitive centromere sequences and to compare them with other childhood cancer samples. Sarra said:

“We are only beginning to understand certain parts of DNA. Previous studies have often focussed on DNA as one long string of letters that is similar in all cells of the human body. However, there have been gaps in the string where the DNA sequence was unknown, yet we know that some of these parts of our genome are essential for the successful transfer of DNA in a dividing cell. Recent studies have shown that there is sequence variability between cells in these challenging parts of DNA.

This research project is focused on the identification of DNA sequence changes that are driving either the development of cancer, therapy response or survival outcome in certain types of childhood cancer. Any newly identified mutations will improve our understanding of disease development and could help diagnose cancer more effectively or treat patients more successfully.

One year’s progress

In the first year of her project, Sarra developed computer libraries of sections of repeating DNA that are found in the human genome. Using these, she can measure the length of the centromeres in cell samples. She said:

"We have proven that our methods can identify DNA sequence variation within ‘genomic dark matter’ between people from different ethnicities. This demonstrated the accuracy of our approach by using individuals who we know have DNA sequence variation.

Next, we will apply these approaches to thousands of childhood cancer patients, to explore DNA sequence variation that may initiate or promote cancer development.

Sarra’s project will finish in 2025, and she has a lot to do. By looking at childhood cancer samples over the coming year, Sarra hopes to see whether different amounts of variation in the centromere can be linked to different patient outcomes. Sarra said:

“Current knowledge of ‘genomic dark matter’ is very limited, so this project has the potential to have an impact on the future management and treatment of childhood cancer patients. This year, we hope to present our work and some of the novel computational methods that have enabled us to analyse ‘dark matter’ at the CCLG Annual Conference. It is an excellent opportunity to discuss the output and potential impact of our research with clinicians and academics.”

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG