Over 200 years ago, an English doctor called Percivall Pott was the first scientist to show that a cancer may be caused by an environmental trigger. He saw that a specific type of cancer was common amongst young chimney sweeps. Realising that there was a link between exposure to soot and the cancer, he lobbied the government for rules to stop young children from becoming chimney sweeps, and to make sure employers provided protective clothing.

This is how most research begins – with an observation. Whilst scientific thinking and methods have advanced significantly, this basic idea hasn’t changed much. For example, researchers might wonder whether a phenomenon they have seen, such as the way cancer behaves, could be investigated to find a new way to treat cancer. So, what has changed through the years?

The 1800s

Whilst we have evidence that cancer has plagued humans since before records began, the 1800s are when scientists started working to understand how childhood cancer behaves and how to prevent it. Here are some examples.

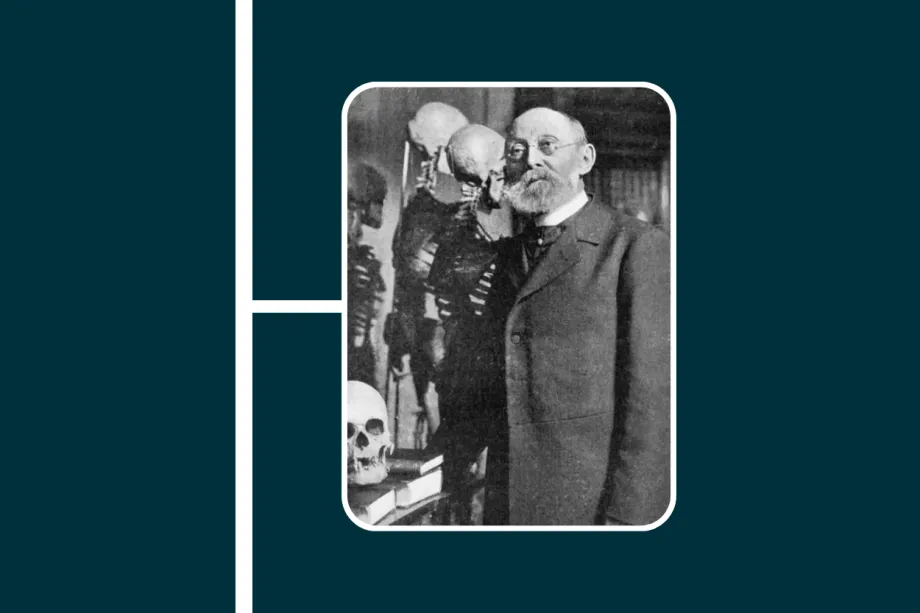

Dr Rudolf Virchow was the first to notice the large amount of white blood cells in the blood of cancer patients, which he named ‘leukaemia’.

Dr Rudolf Virchow

Hilário de Gouvêa, a Brazilian doctor, discovered the possibility of cancer predisposition syndromes. His account of a childhood eye cancer survivor, who fathered seven children, of which two children suffered from the same disease, is thought to be the first known evidence of cancer risk being passed on from a parent to their children.

We will all have likely heard of Marie Curie. She is a well-known scientist who discovered the radioactive elements called radium and polonium. She worked with her husband, Pierre Curie, to understand the way that these elements worked and their potential use in cancer treatments.

Professor Marie Curie

The Curies' discovery that these radioactive elements could destroy cancer cells was then used in early forms of radiotherapy, now one of the main treatments for cancer. Sadly, she did not realise that her constant exposure to radiation was damaging her health and she died in 1934.

The 1900s

This is the century of progress and firsts – the first time cancer is treated with radiation, the first time genetics are thought to play a role in cancer, and the first experiments showing that chemicals can cause cancer. But what really changed in the 1900s is the way doctors thought about childhood cancers.

From the start of the 1900s to as late as 1970, it was thought that the most you could do for children with cancer was to keep them as comfortable as possible whilst their cancer progressed. Dr Jan Kohler, a consultant paediatric oncologist who works with CCLG, said “I always remember reading my paediatric textbook at medical school in the early 1970s that said ‘children’s cancers were almost invariably fatal, although some could be managed for a few months’.”

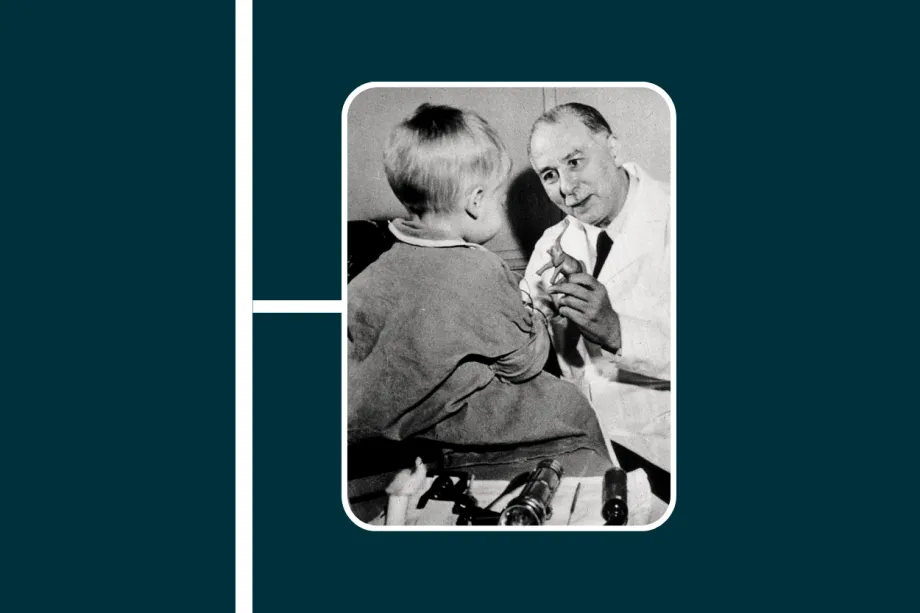

In 1947, Dr Sidney Farber was the first doctor to achieve a partial remission of leukaemia. Whilst the cancer did eventually return, it was the first step towards modern treatments. In the 1960s, doctors started to work on ways to diagnose leukaemia, as well as finding new chemotherapy medicines and deciding the ultimate goal: complete remission.

Dr Sidney Farber

Before 1970, researchers worked on overcoming obstacles such as doctors who opposed chemotherapy and didn’t trust clinical trials because they wanted to decide how to treat their patients themselves. At this point, fewer than three in ten children survived cancer. There were no specialist cancer doctors and nurses, no specific training, no specialist hospitals, and most children with cancer were treated by their GP.

This all changed in 1977, when UK Children’s Cancer Study Group (UKCCSG) was formed. This group was the forerunner to CCLG and aimed to set up clinical trials and collect data to advance our understanding of childhood cancer. This year saw the start of UKCCSG’s first clinical trial and the first recruitment drive for children’s cancer specialists.

By the 1980s, UKCCSG had trials running in five different types of childhood cancers, over half of children with cancer were treated at UKCCSG specialist centres, and there were training programmes for doctors and nurses working with children with cancer. In this decade, there was also a switch from the ‘cure at all costs’ mindset to considering what side effects treatment causes and how to improve the experience for a child with cancer.

The 1990s was a time of new medicines, combinations and ideas. Doctors developed treatment options for specific types of cancer and started to combine chemotherapy drugs to cure many more children. This was also when scientists started thinking about the child’s quality of life, both during and after treatment. In 1998, researchers in the US and Canada launched a study to monitor the long-term effects of childhood cancer treatment.

The 2000s

At the start of the 21st century, the first human genome was ‘mapped’ – meaning every gene in a person’s DNA was able to be identified and analysed. This was a huge accomplishment, which paved the way for whole genome sequencing tests. Doctors can use the results of the test to find out more about a child’s cancer type and what treatments would work best.

Following on from the concerns in the 1990s about long-term side effects, or ‘late effects’, the research into late effects on life expectancy and quality of life continued – and are still ongoing. For example, in 2007, a clinical trial found that aggressive chemotherapy had no added benefit for children with intermediate-risk neuroblastoma, so the amount of intense treatment they had could be reduced. This had the potential to improve the quality of life for many children treated for neuroblastoma.

The 2010s

In 2016, researchers found that survivors of childhood cancer were living longer and staying healthier. They put this down to the increasing awareness of the side effects of harsh chemotherapy and the development of newer, kinder treatments. They found that 50% more survivors who were treated in the 1990s were alive than those treated in the 1970s. They expected this trend to continue, so it would be interesting to know how much further our understanding of late effects has come.

CAR-T therapy was first approved in 2017, marking a huge shift in the way childhood cancer was treated. This was the first ‘gene therapy’ for cancer – a way to engineer a patient’s own cells to fight cancer. Doctors take a patient’s own white blood cells, which normally fight infections and find and kill broken cells, and equip them so that they can recognise the cancer cells within the child’s body and fight them. It is a fantastic advancement, using a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer.

Most research now focuses on kinder treatments, more targeted treatments, addressing late effects, and searching for effective treatments for cancers with low survival rates.

Our researchers now.

We have seen huge progress from the early days of scientific discovery in the 1800s, to the ‘cure at all costs’ approach during the 20th century, through to the personalised medicines of today where patients can have a targeted treatment plan for their specific cancer type. Our researchers are continuing to help change the future for children with cancer.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG