Adult cancer research has been ongoing for over a hundred years. However, childhood cancer research has only really got off the ground within the last six decades.

Despite this, researchers have managed some truly fantastic improvements in that time. Survival rates have increased from just three in ten children surviving their cancer in the 1960s to over eight in ten children today.

Over eight in 10 children now survive their cancer for five years or more.

It is estimated that there are currently over 35,000 survivors of childhood cancer in the UK. Many survivors may have undergone harsh and intensive treatments which can cause a range of long-term effects such as breathing issues or a greater risk of heart disease.

However, many survivors can and do live happy and healthy lives, achieving all sorts of amazing things. Ro Cartwright was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 1968, back when the overall survival rates were just 30% and the primary treatment was radiotherapy.

Ro Cartwright now, 55 years after her cancer diagnosis.

Since Ro was treated, survival rates and types of treatment have hugely improved. Researchers continue to work hard so that the next generation of patients has the opportunity to not just survive, but also to thrive.

I do sometimes wonder about who I would’ve been and what my life would’ve been like if I’d not had cancer but try not to dwell on that. Instead, I try to find positives if I can. My love of reading, for example, stems from time spent in hospital and I know my childhood illness has motivated me to try to live healthily because I want to do everything I can to stay well. I’ve had a lifelong love of exercise and I love spending time outdoors, especially in the mountains. In childhood I was very keen on swimming, but nowadays my main interest is running. My ambition is to run the London Marathon one day!Ro Cartwright

Survive and thrive

Now so many children survive their cancers, parents and doctors want to make sure that these young people can go on to live a full and long life. To do that, we need research into how to make toxic treatments safer, how to reduce treatment for those with low-risk cancers, how to improve supportive care to make sure children feel safe and cared for, and finding innovative treatments that can attack cancer cells in new ways.

The problem with many treatments is that they are not able to attack just the cancer cells. They are much more effective at killing cancer cells than healthy cells, but healthy cells do get caught in the crossfire.

One part of improving people’s quality of life after cancer is trying to make sure as few healthy cells are harmed as possible. Looking at research funded through CCLG, we have projects that are trying to find out who could be cured with less intensive treatment, how to make sure babies get the right amount of chemotherapy, and how to combine lower doses of two medicines to get the same effect as one toxic high-dose drug. With survivorship becoming such a big focus, research groups worldwide are working very hard to make sure each child gets a treatment that is tailored to their needs and targeted to their specific type of cancer.

Holistic cancer care

Survivorship isn’t just about the long-term physical effects of cancer. Mental health is very important for people who have gone through cancer treatment as a child – just last year our survey showed that one in three survivors experience issues with their mental health.

Survivors not only need better tailored follow-up care, including easy access to psychological support, but there are improvements that can be made whilst someone is going through treatment. Things like psychological support during treatment and supportive care that makes sure any nasty side effects, like nausea, are treated and prevented can make a huge difference to how survivors feel when they look back at their time in treatment. The impact of going through cancer in your formative years really cannot be overstated, and it is easy for experiences from that time to become lodged in a person’s brain, leading to difficulties later in life.

This is a relatively new focus in childhood cancer research, and there are not that many charities that fund this type of research. We are proud to be supporting Dr Sam Malin’s work into acceptance and commitment therapy for brain tumour survivors, alongside a number of other quality of life related projects.

Nothing about us without us

Another recent change in the world of research has been the inclusion of people with lived experience – people who have been through cancer treatment and their loved ones. Parents and survivors want to have an input into how research is conducted, and to make sure that it can have a real impact on children’s lives in the future.

Some researchers include people with lived experience on their teams, taking advice on how to engage the childhood cancer community, what is important to that community, and what is reasonable to ask of patients and families who are enrolled on research projects. However, this is still not very common, and we really want to encourage researchers to include more lived experience partners in their work.

Jack Brodie, who was diagnosed with skin cancer age 16, now helps and advises teenage and young adult cancer researcher Wendy McInally on her project.

It’s not just enough for parents and patients to get involved once a project is funded. They have valuable insights, and their experiences mean that they know which issues have the most impact on children and families going through treatment. It is important that people with lived experience are involved in deciding what gets researched. Luckily, we were part of funding a study which did just that. Last year, we announced the top ten priorities in childhood cancer. These priorities were chosen by parents, children, survivors, and the professionals who care for them.

The Children’s Priority Setting Partnership workshop attendees with the final top 10 priorities.

An interesting finding from this was that not all the priorities were about discovering a cure – six of the top priorities were focused on improving the experience of cancer care and understanding long-term effects of treatment.

This is a bit of a game changer in childhood cancer research, and lots of charities are trying to work out how to honour these priorities. It is now part of our criteria for assessing CCLG grant applications that the research project needs to address one of the top ten priorities. It is a huge step forward in knowing what the childhood cancer community needs, and we believe it will lead to more focused and relevant research that will make a real difference.

Growing need for collaboration

As we learn more about each type of cancer, researchers are finding more subtypes. Often, these subtypes of cancer need different treatments. However, how can doctors test these treatments when there are so few patients with that cancer – and that’s before you split out patients with different subtypes of the cancer.

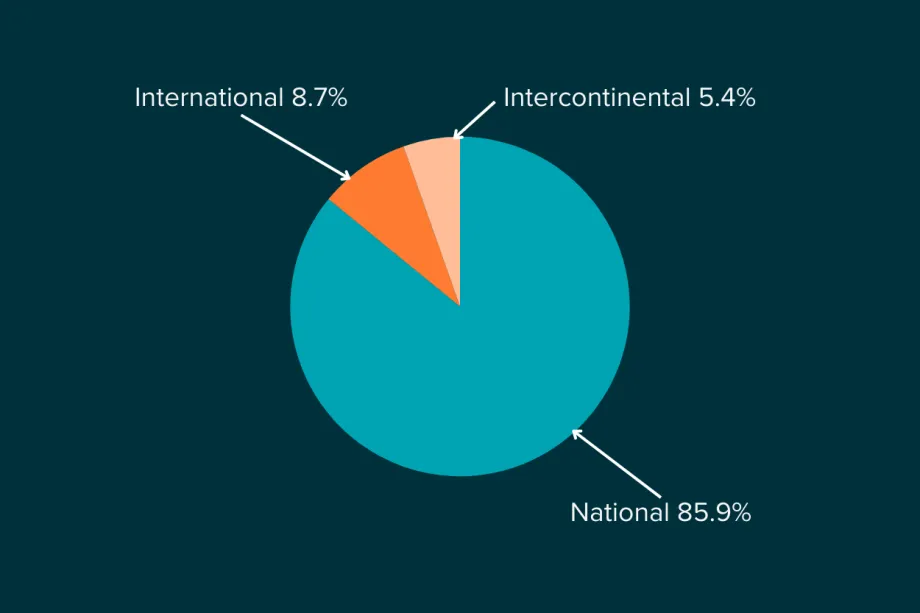

To conduct meaningful research, we need to work together. Childhood cancer is a global problem, and so we need countries to come together to address it. However, collecting data across different countries with different ethics policies and different ways of treating cancer is very difficult. There is a lot more infrastructure needed to support more international research. Between 2010 and 2020, less than 15% of clinical trials for children with cancer were international.

Most research isn't international - only 14.1% of childhood cancer clinical trials open in more than one country.

However, there are a number of international childhood cancer research projects that are ongoing, and every new project makes it a little bit easier for future researchers wanting to make a bigger impact by working internationally.

Exciting new treatments

Alongside the wider reforms happening in childhood cancer research, there are some promising and innovative treatments in the works.

CAR-T cell therapy was approved for use in patients about eight years ago, and was a breakthrough treatment for some types of leukaemia and lymphoma. Its claim to fame is that it was the first personalised version of immunotherapy, as it trained a patient’s own immune system cells to find and kill cancer cells.

Now, researchers are adapting this technology to work for other cancers, like sarcomas and brain tumours, and to improve the effectiveness and reduce side effects. If successful, these efforts could make a big difference to childhood cancer treatment.

There are also exciting and totally out of the box treatments being researched, even just within our CCLG Research Funding Network projects. Here are three of our favourites:

Dr Pouliopoulos

Dr Pouliopoulos

Delivering packaged drugs into paediatric brain tumours using ultrasound

Dr Antonios Pouliopoulos is packing chemotherapy medicines into tiny particles that can be directed into the brain by ultrasound, where they can melt and release the medicines where they are needed.

Dr Ewing

Dr Ewing

High-specificity killing of brain tumour cells using the Zika virus

Dr Rob Ewing is looking at brain cancer cells natural susceptibility to the Zika virus to find out how the virus harms cancer cells more than healthy cells, and whether doctors could use Zika virus proteins to treat childhood brain cancers.

Dr Dandapani

Dr Dandapani

‘Starving’ brain tumours to death

Dr Madhumita Dandapani is investigating how some brain tumours are dependent on certain types of amino acids, with the goal of depriving cancer cells of the nutrients they need to survive.

What does the future hold?

There is no denying that there have been truly fantastic improvements for some patients, which should absolutely be celebrated.

However, we need those improvements for children with all cancers. There are huge differences in survival rates between different cancers – for example, whilst nine in ten children survive over five years with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, just two children out of 100 would be expected to survive with a dangerous brain tumour called diffuse midline glioma.

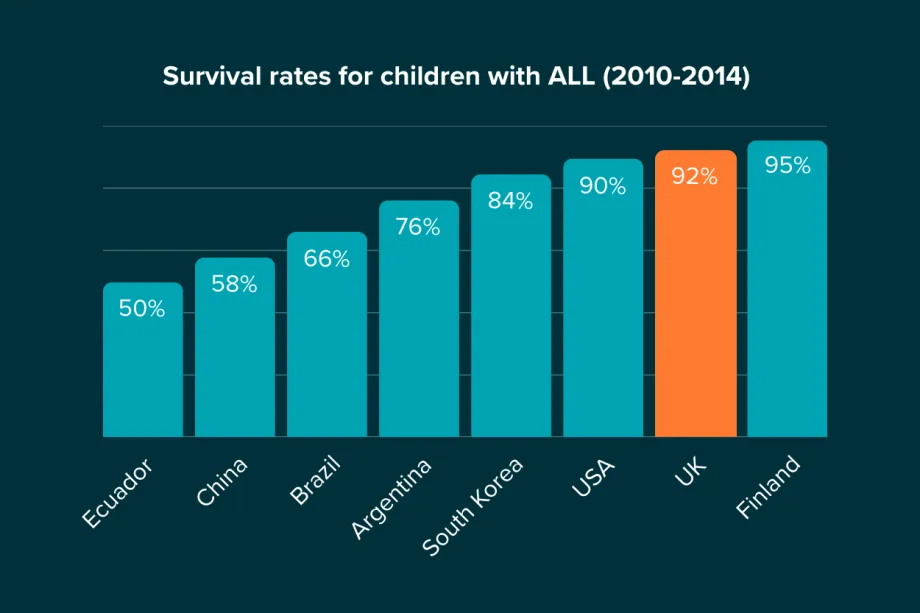

Another issue we need to face is the differences in care between different countries. The 90% survival rate for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is based on children in high-income countries like the UK and the USA. However, around 80% of children worldwide do not have access to effective and evidence-based treatment and care. In 140 countries across the world that are classed as low- or middle-income countries, there may be no data collected about childhood cancer survival or diagnosis and as few as two in ten children might survive their cancer.

In countries that do collect data about childhood cancer, the survival rate for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia can be almost half that of the UK.

Collaboration will be key to solving these issues and, as more and more children survive, we can invest further in making sure that children have long, happy and healthy lives after their cancer treatment.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG