On Saturday 4 February, it is World Cancer Day. The theme for this year is ‘Close the care gap’. It focuses on the need to remove the differences in cancer treatment between countries so that all cancer patients can get the best treatments and care regardless of where they live. As the World Cancer Day website says, “Where you live shouldn’t determine if you live.”

What are the differences for children with cancer?

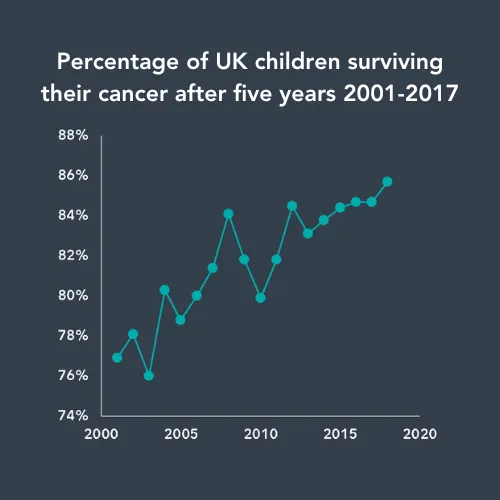

In many high-income countries, around eight in ten children survive their cancer. The doctors treating these children are able to use the latest medicines and equipment to deliver quicker diagnoses, more effective treatments, and have access to specialist training to help improve their medical knowledge and skills within paediatric oncology.

However, around 80% of children worldwide do not have access to these treatments or resources. In low- or middle-income countries (which used to be referred to as developing countries), as few as two in ten children might survive their cancer. This is due to many factors; late diagnosis, cost of treatments, or the right medicines aren’t even available – only around 30% of low- or middle-income countries (LMIC) have good access to anti-cancer medicines.

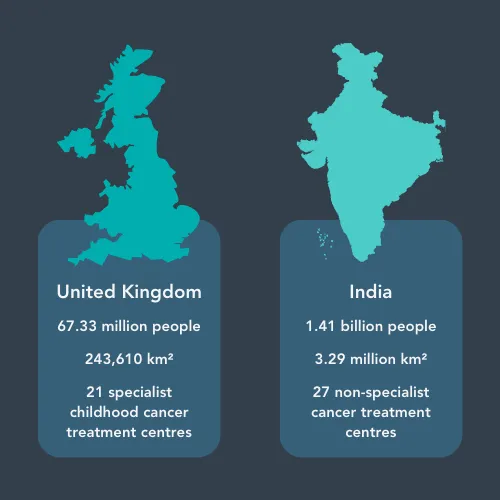

In the UK, there are 21 specialist childhood cancer treatment centres – that’s around one centre per 250,000 people. In India, a country that is over 1250 times larger than the UK, there is only around one general cancer centre per 52 million people.

How is data gathered to show the differences?

The first step to assessing the childhood cancer care gap is gathering data. Many LMIC don’t have cancer databases (called registries) which record the number of patient cases, what treatments they had and whether the treatments were successful. Having this information would help show where more work was needed – for example, if the data showed poor outcomes for children with leukaemia, researchers would know to focus on finding out why.

As the UK has a cancer registry, there is reliable and comprehensive data about how many children are diagnosed with cancer each year, whether their treatment was successful, what type of cancer they had, and much more.

However, registries can only show the number of children who are actually diagnosed with cancer. There are a lot of steps that happen before diagnosis is reached. For example, the child first goes to see a local medic or to hospital, which is not always easy when hospital appointments cost money and may be far from home. Next, the child sees a healthcare professional who refers them to a doctor capable of recognising and diagnosing cancer.

Diagnosing cancer is not always straightforward. In the UK, where there are fewer barriers to accessing healthcare, it’s estimated that one GP will see around three to four cases of childhood cancer in their entire career. In total, one GP practice will see around one case of childhood cancer every two years. Also, some cancer symptoms, like tiredness or recurring infection, can be so vague that they are attributed to other more common illnesses. This shows how difficult it is to recognise cancer straightaway, even in high-income countries.

Will more money help?

Funding is needed to address the global challenges in treating childhood cancer. However, it’s not just a question of more money, it’s also a question of correct allocation of funding. Currently, only 6% of childhood cancer research funding globally goes into improving health services.

For many LMIC, research into new medicines will have little effect on their ability to help children – not only do they still not have reliable access to current older treatments, they don’t have the facilities to properly deliver treatments. Hospitals can be lacking the supportive care that helps to make harsh treatments tolerable, access to emergency departments, or the intensive care beds needed for high-risk treatments. These countries desperately need investment into their healthcare infrastructure in order to improve outcomes.

Can treatment be given differently?

There are ways in which the number of children being successfully treated could be increased, without being too expensive. Treatment de-escalation means giving less chemotherapy and is often used in high-income countries to try to reduce the number of side effects of cancer treatments. This means there is evidence that giving lower amounts of chemotherapy than is standard can still treat many of the children who are currently left untreated in LMIC. This would need a relatively small investment of funding that could lead to fantastic increases in survival. Lower intensity treatment also reduces the need for facilities like supportive care and intensive care beds.

There’s a lot that goes into treating a child with cancer. There are obvious costs, like medicines and equipment, but also less obvious ones. For example, without intensive care beds, some treatments are too high risk and could cause further illness.

Sharing more about cancer

Unfortunately, there are a lot of barriers in treating children with cancer in LMIC. Knowledge about childhood cancer in general population can be scarce - some languages don’t even have a word for cancer.

This lack of awareness contributes to a problem that is almost unique to these countries – treatment abandonment. This is when a child doesn’t start or finish a course of treatment that could cure their cancer. There are lots of reasons this might happen - sometimes families don’t fully understand the disease their child has, are scared by the side effects of cancer treatments, or want to try alternative non-medical therapies. Other reasons include being unable to afford treatments and their associated costs, not knowing about aid programs, and there not being adequate care offered.

This shows the need for country-specific information about childhood cancer that is sensitive to local cultures and is accessible in multiple languages.

Teaching local medics how to treat children with cancer

CCLG’s Global Child Cancer group is one of many organisations trying to improve access to cancer training for local healthcare professionals. They have run multiple training workshops for nurses across India and Pakistan which cover all aspects of childhood cancer care from diagnosis to end-of-life care. For many attendees, these workshops were the first formal training for childhood cancer care, showing the importance of training initiatives like these.

Attendees at Global Child Cancer's first Foundation Oncology Skills Workshop for Paediatric Nurses.

How is change happening?

We know that there is still a mountain to climb. But it is possible, and there are many groups trying to improve childhood cancer care globally. Here are some of the organisations fighting to help children in LMIC:

World Health Organisation (WHO): In 2018, WHO launched the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer with the goal of bringing the global survival rate for childhood cancer up so that six out of every ten children diagnosed with cancer survive. The initiative focuses on creating childhood cancer centres with excellent networks that can deliver proper cancer care, ensuring that patients can access care without money problems, creating realistic diagnosis and care plans, and setting up databases to allow for evaluation and monitoring.

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital: St Jude’s joined forces with WHO in 2021 to announce the Global Platform for Access to Childhood Cancer Medicines. The platform aims to ensure that children with cancer can receive high quality cancer medicines without supply issues. They will do this by providing end-to-end support, including developing treatment protocols and building databases to monitor care.

International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP): In 1990, SIOP launched the Global Health Network. It aims to ensure all children and young people have access to appropriate care that is suitable to their circumstances, to help national children’s cancer services become self-sustaining, and improve end of life care globally. There are 14 sub-groups all focused on specific issues that will help achieve the Global Health Network’s vision.

World Child Cancer: Founded in 2007, the charity has four main objectives to address the global inequality in childhood cancer care. They aim to improve treatment accessibility and availability, support families to make the cancer journey easier, work with communities and healthcare workers to ensure earlier diagnosis of cancer, and advocate for children with cancer globally.

CCLG: The Children & Young People's Cancer Association: Alongside our other work, we support research projects aiming to improve childhood cancer care in countries like Uganda and Tanzania. Many of our professional members are part of our Global Child Cancer group. The group have run training workshops for cancer care professionals and produced leaflets for parents and families caring for children with cancer in eight languages to support those going through the cancer journey.

A patient being treated at Muhimbili National Hospital in Tanzania.

It is possible to significantly improve the global survival rates. If we can ‘close the care gap’, it could help nearly 150,000 children with cancer in LMIC per year. Not only would this save lives, but could also have untold benefits to society at large - who knows who these children could grow up to be?

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG