When medicines are approved for use in the UK, it is often for a specific purpose. They will have undergone extensive testing and clinical trials, which can take 10 years or more, so we know they are safe to use in people.

A lot of the medicines used to treat children and young people are used ‘off-licence’. This means that the medicine is licensed to be used differently, for example, in adult cancer. This is the case even for commonly used medicines like vincristine and doxorubicin.

Although they are not officially licensed for use in children and young people, there is a huge amount of research into how effective these medicines are against cancer. You can be assured that if your child was treated with an off-licence chemotherapy, they had the best treatment available for their cancer at the time.

It’s quite common for drugs licensed for adults to be used for other ages. However, there is another type of off-licence medicine – those being used for something completely different to their initial purpose. For example, amitriptyline is licensed as an antidepressant but is also used to treat chronic pain and migraines.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence lists over 1700 drugs on its website. There is an amazing variety, from standard medicines such as ibuprofen to very specific drugs like wasp venom extract, which is used in patients with severe allergic reactions. So, wouldn’t it make sense that one of these 1700 drugs could also help young people with cancer?

Repurposing medicines for Ewing sarcoma

In 2021, Dr Robin Rumney and Professor Dariusz Gorecki began their Little Princess Trust-funded project at the University of Portsmouth into whether a diabetes medicine could reduce the growth of Ewing sarcoma cancer cells.

Ewing sarcoma is the second most common type of bone cancer for young people and can have very different survival rates depending on how it behaves. When the cancer is just in one bone, seven out of ten patients survive for five years or more. However, if the cancer has spread to other areas, the survival rate is less than 30%.

Cancer is not static – there are many thousands of cells growing, dying, interacting with the immune system and the treatment, and gathering genetic mutations. Sometimes, this leads to changes happening in the tumour that make it more likely to spread.

One of these changes results in a lot more of a molecule called DPP-4, which researchers have linked to increased cancer growth and more chance of spreading. However, DPP-4 also causes problems for people with diabetes by disrupting insulin production.

Robin said: “Gliptins have been made to treat diabetes by blocking DPP-4’s function. Because DPP-4 is also present in Ewing sarcoma, I wanted to test whether these drugs might be effective for Ewing sarcoma.

It takes roughly 10 years to make a new drug from scratch, and the necessary clinical trials cost hundreds of millions of pounds. I think that drug repurposing is a better option. Not just because of cost, but time as well. New drugs spend a long time in clinical trials to test their safety, but repurposing uses drugs which we already know are safe.

Dariusz added: “We also already know what the side effects are. Therefore, it's easier to spot side effects when the drug is repurposed for new patients.”

Testing the theory

In Robin and Dariusz’s project, they looked at how common DPP-4 and other cancer-interacting molecules like neuropeptide Y (NPY) are in Ewing sarcoma tumours. They also wanted to confirm whether these molecules were associated with certain cells to see whether immune cells were helping Ewing sarcoma tumours grow.

Finally, they planned to investigate how gliptins affect Ewing sarcoma cells in the lab, and whether this could form part of a new cancer treatment.

Dariusz and Robin used two different ‘cell lines’ for their research. These are lab-grown Ewing sarcoma cells that have been taken from a patient and stabilised so that they can be copied repeatedly as research demands.

However, the two cell lines come from two different patients with differences between their cancers, so they can behave differently. For example, the researchers found that NPY and DPP-4 were sometimes found at different levels in each cell line.

Luckily, a gliptin drug called linagliptin was able to affect both types of cancer cell. Robin explained:

We found that linagliptin reduced the viability of cancer cells in two different Ewing sarcoma cell lines and two different conditions. The fact that gliptins worked on both cell lines shows that the treatment is more likely to apply to Ewing sarcoma as a whole, rather than just one subtype.

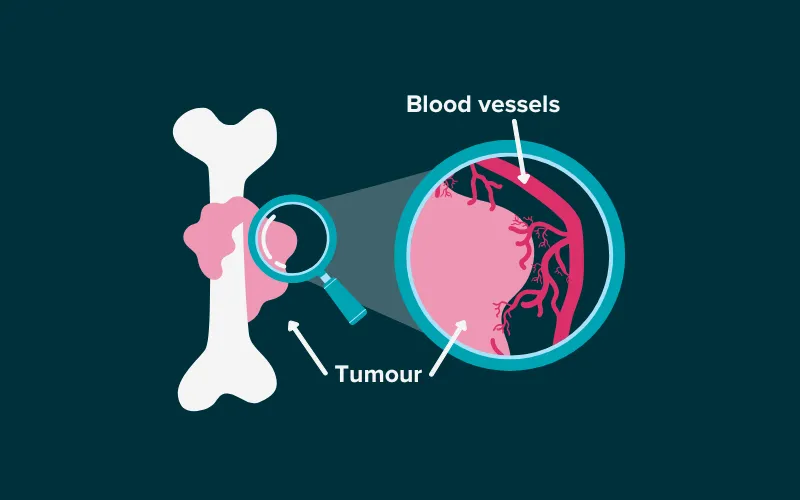

“If you imagine a tumour as a lump or a mass with few blood vessels carrying oxygen inside, it makes sense that the interior of that tumour is generally going to have less oxygen available than the surface. That means we have these different conditions for cells to live in, which are high oxygen and low oxygen, relatively speaking. We've demonstrated that the drug works in both high and low-oxygen environments.”

Blood vessels carry oxygen to the surface of the tumour, but struggle to get oxygen into the core of the tumour, creating low- and high-oxygen environments.

He added: “I am still cautious about our results because we used cells grown in a petri dish, which is not the same as an actual tumour. The effects of the linagliptin are also quite small, so we’re only seeing roughly 10% of cancer cells being killed off.”

For a repurposed medicine like linagliptin, which is known to be safe for many patients as it is routinely used for diabetes, a small effect is still exciting for Ewing sarcoma researchers. As less investment is needed to make linagliptin available for children with cancer, and it is already known to be safe, it could be used in combination with existing treatments.

An unexpected finding

This project also had an unexpected finding – that a common way to grow cancer cells in the lab could impact research results. In order to grow cancer cells, researchers mix up a cocktail of ingredients that provide the cells with nutrients and the other things they need to survive. Dariusz and Robin found that one of these ingredients, a liquid called foetal bovine serum (FBS), was full of NPY proteins – one of the proteins they were trying to stop the cancer cells from using. If this had gone unnoticed, it could have had a big effect on their results, making it harder to know whether treatments were working on Ewing sarcoma cells.

Robin said: “We had some really strange effects early on when we changed one batch of FBS to another.

We did some research and, to our surprise, FBS is loaded with NPY. I thought there might be some, but the amount surprised me. If you're trying to inhibit a molecule but it’s actually in the liquid you’re growing cells in, it's going to get in the way of uncovering the facts.

“I think people will have to take this on board with their future research because otherwise they might be working on something in the FBS and not something that's been released by the cancer cells.”

Dariusz added: “It's important because we are trying to standardise conditions for our experiments and, at the same time, we are using highly variable additives like FBS to grow cancer cells.”

“Researchers should be aware that they need to test whether the critical ingredient they are researching is already present in the FBS.”

What’s next?

Now based at the University of Southampton, Robin plans to continue his work on Ewing sarcoma. Not only does he have plans for future work on gliptins, but he will also work on the data generated from this project about immune cells in Ewing sarcoma.

He said: “I certainly hope we can continue with the gliptins because there are promising results there. It'd be interesting to look at human tissue sections, where we could study the factors inside immune cells and Ewing sarcoma cells. Testing the treatment in animal models is important too, such as investigating whether a mouse with Ewing sarcoma responds to gliptin treatment.”

Dariusz added:

There are drugs that can kill 99.9% of cancer cells - but the 0.1% of cells that survive are resistant to any known treatments. I'm not saying that gliptins will kill these cells, but this kind of drug may be able to because it uses completely different mechanisms than mainstream drugs. It's important that we have a spectrum of drugs that can eliminate cancer cells through different mechanisms. It is also particularly important to have drugs that have very few side effects, such as gliptins, because we can quite safely add them to other treatments. So, a combination therapy could be effective.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG