There’s a lot of buzz these days about immunotherapy, a treatment that uses a patient’s own immune system to fight their cancer. However, this type of treatment has existed for quite a while – the first FDA-approved immunotherapy treatment for cancer was released in 1986!

A lot of the excitement about immunotherapy is down to the revolutionary CAR-T therapy, which was approved for use in 2017. CAR-T therapy stands for ‘Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell’ therapy and can be used to treat some types of blood cancer.

In CAR-T therapy, doctors take a sample of your blood and train some of your own immune cells, called T-cells, to recognise and kill cancer cells. When the trained cells are put back into your body, they find and kill cancer cells.

CAR-T therapy is a fantastic advance in treatment, but it only works for specific types of cancer. The NHS currently only use it for two types of cancer, and only if all other treatments have been unsuccessful. Whilst there is ongoing research to find out whether CAR-T therapy could work for other cancers, like in the NextGen Grand Challenge project, researchers are also working on finding other types of immunotherapy.

A new type of immunotherapy

Dr Jonathan Fisher, at University College London, works on osteosarcoma, which is a type of bone cancer. It affects mostly teenagers and can need intensive treatment such as chemotherapy or even amputation. Despite this, the cancer becomes untreatable in around half of patients.

Dr Jonathan Fisher

Immunotherapy can work where other treatments haven’t and can have fewer side effects, which makes it a tempting option for osteosarcoma patients. However, CAR-T therapy doesn’t work for osteosarcoma, because the engineered immune cells struggle to get to the cancer cells and kill them.

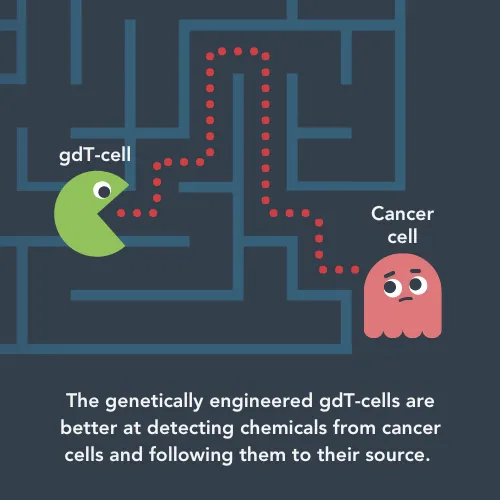

Jonathan is using a different cell as the base for his new immunotherapy. These are called gamma-delta T-cells (gdT-cells). This type of T-cell is found in more places in the body, whereas the cells CAR-T therapy uses are mainly found in the blood.

He said:

Cancer that starts in the bone or spreads to the bone is often resistant to chemotherapy. Immunotherapy uses a different approach and we now understand more about how to harness its power.

"Conventional CAR-T cells usually have to be made from a patient’s own immune cells, which is expensive and takes time. Gamma delta T cells can be safely taken from a healthy donor and given to patients. Therefore, treatments using gdT cells can be prepared beforehand in batches, reducing cost and time to delivery."

Funded by The Little Princess Trust, Jonathan is engineering gdT-cells to form an efficient new immunotherapy for osteosarcoma. Whilst normal gdT-cells are good at fighting infections and rogue cells, they need improvements to be a reliable and effective cancer treatment.

So far, the Fisher lab has made a gdT-cell that can ‘sniff out’ chemicals released by cancer cells. The cells can follow these chemicals to the tumour. In this project, Jonathan is focusing on osteosarcoma, but the same approach could work for other cancers if there are chemical trials the gdT-cells can follow.

When the gdT-cells get to the tumour they need to kill cancer cells and survive long enough to keep finding cancer cells to kill. They can only kill cells that are covered in antibodies – tiny proteins your immune system uses to flag up problems. Other types of immune cells normally make these antibodies, but Jonathan’s team has engineered the cells to produce their own anti-cancer antibodies.

So, their immunotherapy treatment can now find and kill cancer cells due to their antibodies – but for how long?

Jonathan said:

There’s no point giving someone anti-cancer immune cells if the cells don’t survive long enough to attack the tumour. Gamma-delta T cells rely on external support to survive when they’re grown in the lab, meaning they would die when given to a patient. We got around this by making them produce their own survival signals, keeping the cells healthy to attack the disease.

Forcing the gdT-cells to produce these extra molecules has an additional benefit – it recruits other types of immune cells in the fight against cancer. With CAR-T therapy, the engineered T-cells are the only thing trying to kill the cancer. In Jonathan’s new immunotherapy, the extra molecules can activate ‘natural killer cells’ to help eradicate the cancer.

Jonathan has recently published a paper about the new type of immunotherapy, which has been shared by 26 news outlets and garnered a lot of positive attention.

He said: “This paper represents an entirely different approach to immunotherapy, using gdT cells as a multimodal payload delivery system rather than just anti-cancer cells.

"Our LPT funding helped us prolong the life of our gdT cells and also show how they work using better 3D models of bone cancer. Our approach was much more effective than conventional CAR-T in mouse models of osteosarcoma. We hope that this will provide a foundation to target cancer that begins in, or spreads to the bones."

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG