Cancer Grand Challenges brings together a global research community to think differently and to take on cancer’s toughest challenges. They were launched in 2020 by Cancer Research UK and the National Cancer Institute (part of the National Institutes of Health, US) who wanted to address the most important unanswered questions in cancer research and covers a range of different areas such as how to stop chronically-ill cancer patients from losing too much muscle and fat, to finding out if e-cigarettes have long-term health risks.

Cancer Grand Challenges happen at a much larger scale than many other research projects. For example, a 2017 Grand Challenge project working to create a map of tumours, detailed down to the molecular activity within each cell, employs over 70 expert physicists, biologists and chemists. In the past four years, the team have produced 22 scientific research papers, created and refined a way of processing data into images that has been adopted into 85% of AstraZeneca’s drug development projects, and discovered two potential drug targets. This huge amount of work couldn’t have been possible without the funding of so many experts in their fields.

A Cancer Grand Challenge for children

While previous challenges have focused on broad discovery research to advance our understanding of cancer, such as the development of a new way to build a 3D map of a tumour, or with relevant applications to childhood cancers, such as collecting childhood cancer samples to understand the role of mutations in their development, this is the first time a Cancer Grand Challenge has been set to focus solely on the unique challenges posed by paediatric cancers. The challenge is called ‘Solid tumours in children’ and aims to find new treatments for children with solid tumours, such as brain tumours, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Wilms tumours (amongst others).

Many children with this type of cancer will have chemotherapy, based on medicines discovered decades ago, which can have serious and long-term side effects like developmental problems, new cancers later in life and heart problems. Children who relapse have even fewer options, and treatments can be even more aggressive.

Dr Kevin Litchfield, who works at the University College London Cancer Institute, said:

The minimal efficacy of current immunotherapy drugs in childhood solid tumours is really heart-breaking – we know how transformative immunotherapy can be in adult solid tumours and haematological malignancies – so it’s an upmost priority to find novel immunotherapeutic approaches that work in childhood cancers.

The Cancer Grand Challenge winners

The winning team for the ‘Solid tumours in children’ challenge is called ‘NexTGen’. It is made up of many experts across eight different research institutions within three countries and plans to create better immunotherapy options for children with sarcomas and brain tumours.

The Cancer Grand Challenges NexTGen Team.

“With our Cancer Grand Challenge, we hope to bring next-generation CAR T-cell therapies to children with solid tumors,” said team co-lead Professor Catherine Bollard, from the Children’s National Hospital in the USA. “What excites me most is the energized, passionate group of people we’ve brought together to take this challenge on. Big problems remain to be addressed, but we believe they can be solved, and that we’re the team to solve them.”

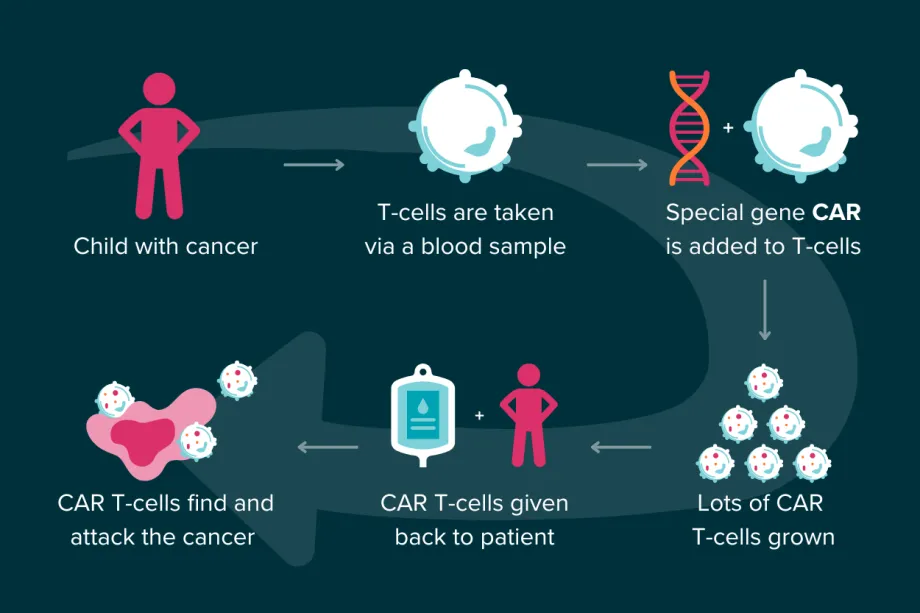

The NexTGen team will be concentrating on a type of immunotherapy treatment called CAR-T therapy. CAR-T therapy stands for ‘Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell’ therapy. T-cells are an important part of your immune system and work to identify and destroy intruders like bacteria or pathogens. T-cells are also supposed to kill cancer cells, but sometimes the cancer cells can hide from them. In CAR-T therapy, doctors take a sample of your blood and train your T-cells in it to recognise and kill the cancer cells. When the trained cells are then put back into your body, they will seek out and kill cancer cells.

It is a fantastic advance in treatment, but it only works for specific types of cancer at the moment. The NHS currently only use it for two types of cancer, and only if all other treatment has been unsuccessful. If successful, this project could allow CAR-T therapy to be used in many more types of childhood cancer.

How CAR T-cell therapy works.

NexTGen’s next move

To be able to target cancer cells with T-cells, the team will first look at ways the T-cells can identify them. Cells have tiny molecules on their surfaces, called antigens. These tiny molecules can identify what a cell is and whether it is healthy. We know a lot about what antigens mean in adult cancers, but it could be very different for childhood cancer. Once they have found the right antigens, the researchers plan to create new receptors that can target them, so that T-cells can lock on to cancer cells.

Another part of the project is to make sure the T-cells and receptors can survive inside a tumour. Tumours often create a microenvironment inside themselves, making things like the amount of blood vessels and types of immune cells very different to normal conditions inside the body. This can help make the tumour resistant to treatment.

In order to test their newly engineered T-cells, the researchers plan to create a new type of model. This model will mimic a 3D cancer tumour so that researchers can test a cancer’s reaction to different medicines. However, many models don’t include how the immune system interacts with both the tumour and the treatment, which makes it very difficult to accurately test treatments like CAR-T therapy. The NexTGen team will use computer modelling to predict how cells interact, as well as using immune cells from real patients.

Last but not least, they will begin three early clinical trials that will test different ways to make the special T-cells. This will be started early on, so that results from the trials can help the researchers decide which option to use going forward. All of this work will be carried out over the next five years.

How parents are involved

At CCLG we're always keen to see investment in childhood cancer research, and we're excited to see how this project will benefit children with cancer over the coming years. You can read a lot more about it on Cancer Grand Challenge’s website – they have a blog too!

One of the PPI representatives for this project is Scott Crowther, dad to Ben, who set up the ‘Pass the Smile for Ben’ Special Named Fund at CCLG in memory of his son. Scott said the project gives him, “hope that other families might get viable, successful, less toxic options. It also means a lot personally because doing this PPI role in Ben's name and memory helps me keep him alive in everybody's mind.”

So far, Scott has been involved in planning the patient and public involvement in the research in preparation for the Cancer Grand Challenge application. He says that they “must have done something right because the funding was granted!”

Now the project has started, Scott will be giving a parent’s perspective on the data collection and analysis work being carried out in one of the six teams located around the world. He hopes that the project has “the potential to create a truly new treatment option for kids with some of the rarer cancer types.”

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG