Clinical trials are where researchers get to see their results come to life. The treatments they are working on in the lab are finally tested on humans to find out whether their work could change the way patients are treated. A researcher might have worked on a treatment for many years before gathering enough evidence to support a clinical trial, where it will be tested in large groups of patients.

In research, scientists want to be working on groups that are as large as possible. Bigger groups in cancer research can help make sure the results are trustworthy, for example giving a clearer picture of what treatments do and don't work. If they are working in the lab, this might mean a big group of cancer samples, or in clinical trials it might mean a big group of patients. However, it can be difficult to gather a big enough group, which can limit progress.

There are many types of childhood cancer, however, some are rarer than others. For example, in 2021 there were only 91 cases of kidney cancer in UK children under the age of 15. Those 91 cases can then be broken down by tumour type, such as Wilms tumour or clear cell sarcoma. A trial investigating Wilms tumour might then split patients into groups based on their subtype of cancer, leading to even smaller groups of patients. You can find out why small groups of patients make it harder to do research in our tissue banking blog.

Getting a big enough group to research is particularly a problem in rare childhood cancers. For example, only around 15 children are diagnosed with a type of brain and spinal cord cancer called atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumour (ATRT) per year in the UK. The rarity of ATRT makes it very difficult to study, so scientists aren’t currently sure exactly how common it is. However, running clinical trials internationally means that researchers can work with many more patients. These big trials are rare but exciting opportunities. Not only can new treatments be tested, but lots of cancer samples and data are collected. This means much larger patient groups than researchers can find outside clinical trials, giving them more data to work on.

Working alongside the ATRT clinical trial

Dr Daniel Williamson, from Newcastle University, has been working on ATRT brain and spinal tumours for nearly 20 years.

Funded by CCLG Special Named Funds - the Joel Prince Starlight Fund and Our Buoy Hugo’s Fund - he is working with NHS consultant, and Professor of Paediatric Neuro-Oncology, Professor Simon Bailey, to analyse cancer samples collected through a clinical trial for ATRT.

Simon, on the left, with Daniel.

Daniel said: “The comparative rarity of this tumour is certainly one of the major challenges - we require a certain number of patients to make a study meaningful. That’s why the most exciting part of this project is the fact that it is running alongside the international ATRT trial.

“The trial asks whether it is better to treat patients with radiotherapy or high-dose chemotherapy, with the aim of sparing young children long-term effects associated with treatment. This is the highest level of study we could have hoped for and has been decades in the making.

“Whilst this is a clinical study, it also provides an excellent opportunity to study the tumour samples collected by the trial throughout treatment. My project will ensure that UK patients enrolled on this trial will have their tumours analysed using state-of-the-art techniques.”

Genetic changes in cells

In his project, Daniel is using a process called molecular profiling to look for genetic changes that control which genes are turned on in ATRT cells.

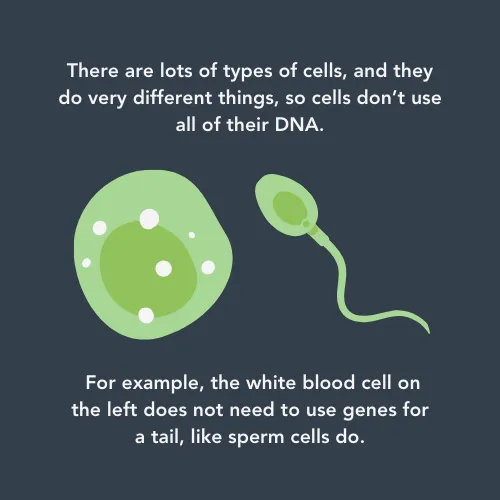

When we talk about genetic changes, we often mean errors or mutations that have changed the sequence of DNA. However, there are other ways that a cell’s DNA can be changed, for example, by affecting the way the DNA sequence is translated into proteins. Daniel is particularly interested in a type of genetic change called DNA methylation.

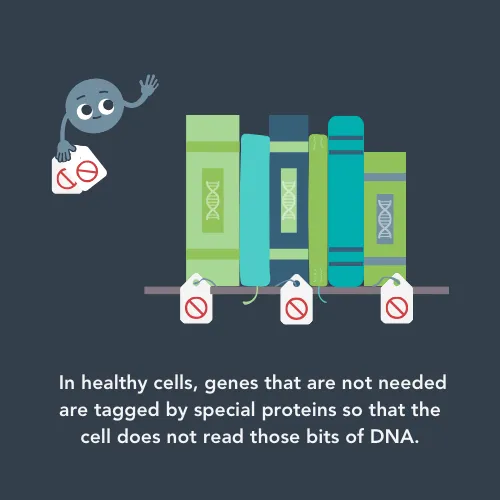

To understand DNA methylation, it’s important to understand that every cell contains all your DNA – not just the bits that a cell needs to do its job. For example, brain cells need very different genes active than skin cells do. DNA methylation is a process where a tiny chemical tag is attached to a bit of DNA that isn’t needed in that cell. This turns off that gene to make sure that a cell only has what it needs to do its job - and that it can’t get confused by incorrect genes being active.

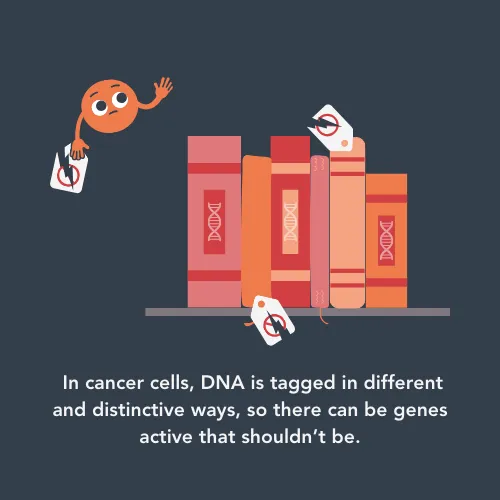

This happens all over your body but it doesn’t work properly in cancer cells. Researchers think that this is because the proteins that attach and remove the chemical tags are out of balance.

In his previous work, Daniel’s team found that they can look at the DNA methylation patterns in ATRT cells and sort the cancer cells into three different groups. These groups appear to have different chances of survival and different responses to treatment, but Daniel wasn’t able to test this fully until the start of this project due to the lack of samples for this rare cancer.

If he can confirm his theory using the clinical trial samples, it would be an exciting development in ATRT treatment. He could create a ‘prognostic model’, an algorithm which would tell doctors how well their patients would respond to treatment based on their DNA methylation patterns.

He said:

For young cancer patients with ATRT, the potential benefit of this work is the very real prospect of, in the future, tailoring treatment to your individual needs. To deliver only the therapy deemed to be necessary, potentially avoiding unnecessary treatments and any damaging long-term effects. Alternatively, when treatment is predicted to be ineffective, to be able to direct patients towards new targeted therapies.

What’s happened so far?

Daniel has just finished the first year of his project. Whilst waiting for the clinical trial to open fully, and to receive the new cancer samples from enrolled patients, he has recruited and trained a new team member. Rose Bailey has now been working with Daniel since October 2023 and will be key to processing samples from the clinical trial.

Daniel said: “So far, we have trained a new technician to handle tissue samples, analyse genetic data, and manage databases. She will use these new skills to proactively manage the movement and processing of samples during the SIOPE ATRT01 trial.

“It’s quite complicated – there are some existing systems in place and some we have had to create with her to ensure that all the sample work for the trial runs smoothly.”

Rose Bailey, the new Research Technician on Daniel’s project.

Whilst the cancer samples from the clinical trial will be key, Daniel is keen to include even more data in his prognostic model to make it more accurate.

Over the past year, he has added more information about ATRT patients to the study, to hopefully ensure the model works for lots of different types of patients. He has also been looking at ways to increase the DNA methylation data included in the model. This has led to a collaboration with another researcher which nearly doubled the amount of data used in the study so far.

Finally, Daniel also has been going through all of the ATRT samples collected in recent years. This means that both old and current patients will have access to high-end genetic analysis – a first for many patients with ATRT.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG