One of the problems researchers face when trying to develop new treatments for brain tumours is that the brain is very picky about what it will let in. Blood vessels in the brain are surrounded by the blood-brain barrier. This barrier stops lots of pathogens, like viruses and bacteria, from getting into your brain, but it also means that some medicines can’t get to where they are needed.

Another problem is that it’s hard to measure how well a medicine or drug has been absorbed into the brain. Previously, researchers looked at whether a person survived longer after treatment to decide whether the drugs were being absorbed into the brain. The problem was that, if the person’s survival didn’t improve, there was no way to tell whether that was because the drug couldn’t get to where it was needed or because the brain tumour was resistant to the drug.

Dr Ruman Rahman's research

In 2016, Dr Ruman Rahman applied to CCLG for funding from The Little Princess Trust to study a new way of seeing whether drugs were killing cancer left over after brain surgery. His research team at the University of Nottingham had developed a biodegradable paste that could be put around where the tumour was before surgery. One of the most important things to show with his research was whether the drugs that were mixed into the paste absorbed into the surrounding brain tissue properly. Now, after four years of study (and a few COVID-19 related disruptions), the team at the University of Nottingham are ready to share their findings.

Dr Ruman Rahman

After checking how well six chemotherapy drugs moved through a sample of brain tissue, Ruman’s team found that carboplatin and dasatanib were the best at getting into brain tissue. Now that they had found the drugs that they wanted to test, it was time for more hard work and some very sophisticated machinery.

What is '3D-orbiSIMS'?

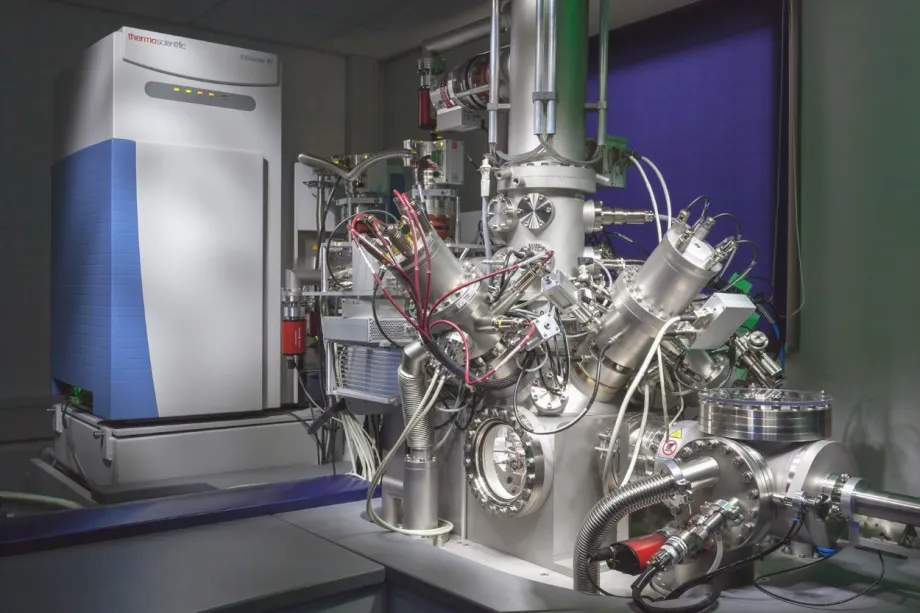

The 3D-orbiSIMS is a secondary ion mass spectrometer owned by the University of Nottingham. In fact, they are the first UK university to have one of these. It shoots a beam of charged atoms (ions) at a sample and then looks at the ions that are forced off the sample because of the beam. It’s sort of like analysing the dust on a table to see what the table is made of, but much smaller and much more complicated. Ruman and his team used the 3D-orbiSIMS to find out how far their drugs had travelled into brain tissue. To do this, they applied their drug-loaded paste to a sample of brain tissue and then immediately froze the brain tissue and cut it into thin slices, so it could be analysed by the 3D-orbiSIMS. They also looked at how far drugs travelled into a sample brain tissue when the sample was left in a bath of the drug (this was to show the affects of medicines that act on the whole body).

3D-orbiSIMS machine

One of the problems the researchers faced was that “the 3D-orbiSIMS instrument is so powerful, that it could detect lots of ions, most of which were from the brain, not the drugs”, Ruman explained. Luckily, they were able to teach the 3D-orbiSIMS how to show only the results from the drugs being tested.

They found that with the 3D-orbiSIMS they could see that the drugs went at least 2mm into the brain tissue in both tests. This showed that this new method of tracking drug movement within the brain works for locally applied medicines like the paste as well as drugs that affect the whole body. Tracking drugs using 3D-orbiSIMS will give a much more realistic view of how medicines move in the brain, because previous methods using radioactive or fluorescent tags make the drug molecules heavier and less mobile.

Ruman hopes that these findings will help show which drugs could be better for treating brain tumours, and therefore get them into clinical trials sooner. All of the data his team worked on will be available to other researchers so that they can use this knowledge to design future studies about brain tumour treatments. He hopes that researchers will start using and expanding on his new method within the next two years, and that this study will have an effect for patients within the next five years.

What's next?

In his next project, Ruman and his team say they “will not only assess whether the drugs are safe to use and how effective they are, but also provide direct evidence of where the delivered drugs have reached in the brain.”

The Little Princess Trust, in partnership with CCLG, has awarded Ruman’s next project the Innovation grant, which funds research at the cutting edge of young people's cancer research. Brain cancer scientists from the School of Medicine have teamed up with colleagues from Pharmacy at the University of Nottingham to help develop the biodegradable paste that began this study. The 3D-orbiSIMS will also be used in the new project, allowing the team to track how the drugs from the paste are absorbed.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG