We all know that we need to eat to survive. However, we also know there are specific things that we need to eat in order to get the nutrients for our bodies to grow and repair.

For example, sailors living off a diet of just salted meat and non-perishables in the 1600-1700s developed a disease called scurvy. It was a nasty disease which was deadly for many sailors – even wiping out entire ship crews. It turned out that this was all caused by a lack of vitamin C in their rather unappetising diet, and the introduction of citrus fruit rations on ships saved many thousands of lives.

This is a great example of how our bodies have specific needs and, if they’re not met, things can go badly wrong. It turns out that cancer cells are no different. In fact, because cancer cells grow and divide much faster than other cells, they need more nutrients than healthy cells.

Cancer cells have genetic mutations, which are changes to the instructions that tell them what to do and how to behave. These mutations allow the cancer to grow and divide faster. Sometimes the mutations make it so the cancer cell is too dependent on a specific nutrient in order to survive.

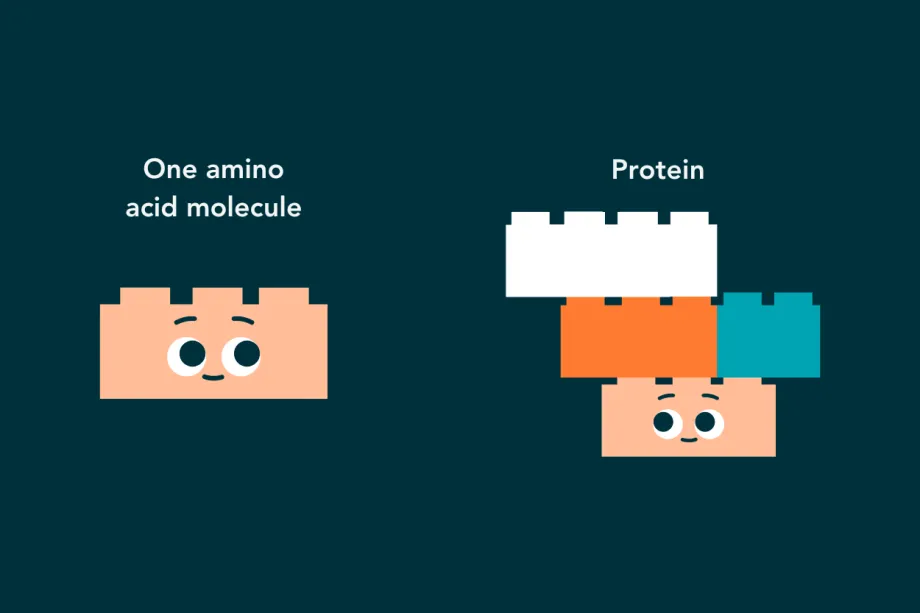

One of the main nutrients that cancer cells need are amino acids. There are 20 different types of amino acids, which are used to make all of the proteins a cell needs to survive and replicate. Healthy cells need these too and can sometimes make and recycle them from other amino acids – but cancer cells often can’t make new amino acids so are completely reliant on getting this nutrient through the diet. Sometimes, these cancer cells even stockpile amino acids to stop immune cells, which also need the same nutrients, from working properly and attacking the tumour.

Amino acid molecules are used like building blocks to make the proteins needed for cell survival.

Why does it matter?

Our sailor story shows that not getting the right nutrients can be deadly. This has a practical application when it comes to cancer - if doctors can take away an amino acid that cancer cells rely on, it could kill the cancer cell. And, because healthy cells can make their own amino acids, it shouldn’t affect healthy cells as much and could be a kinder treatment with fewer side effects. Stopping tumour cells stockpiling amino acids could also help the immune system fight cancer better.

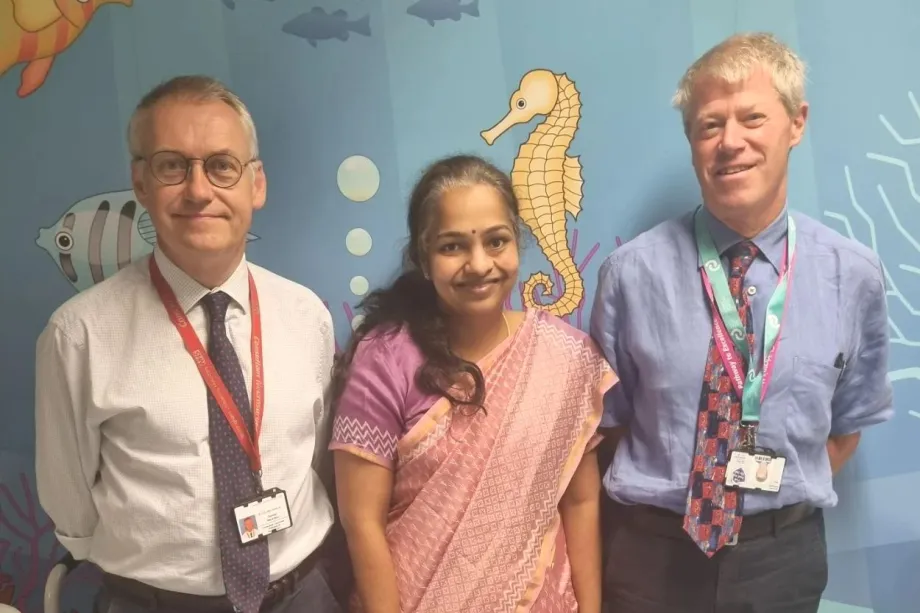

Funded by the Little Princess Trust, in partnership with CCLG, Dr Madhumita Dandapani has spent three years researching how to starve brain tumour cells. She knew that there must be differences in the ways they use some amino acids – it was just a matter of tracking down which ones.

Dr Madhumita Dandapani

Madhumita said: “We know that cancer cells divide faster than normal cells, and that this process of doubling requires a lot of energy and uses a lot of key nutrients. Cancer cells also sometimes have errors that mean they can’t build or recycle certain amino acids. My research is focused on finding ways of starving cancer cells of these key nutrients that normal cells can recycle and cancer cells cannot.

“We initially screened all available information on all of the genes that are part of making or recycling amino acids, across all the different brain tumour types. My team now have a shortlist of amino acid pathways that are altered in each type of tumour, and we are studying these in more detail.”

What do brain tumour cells need?

This project is the first time that certain childhood brain tumours, like ependymoma and glioma, have been shown to rely on arginine, a type of amino acid.

Cells can get arginine from two places – either by absorbing it through the diet or by recycling other amino acids to build it. However, Madhumita has found that these brain tumour cells have mutations that stop them from recycling arginine, meaning that the cells can only rely on absorbing it through the diet.

Cells can sometimes recycle other amino acids to make the one they need. However, cancer cells don't always have the right equipment for recycling amino acids, leaving them vulnerable.

What's next?

As cancer cells can’t make their own arginine, but healthy cells can, treatments that prevent all cells from absorbing the amino acid should have a much bigger impact on cancer cells. It could also help the immune cells around the tumour to function better.

Madhumita said:

Targeting amino acids that are crucial for tumour survival and that normal cells can make themselves, could potentially be a kinder treatment. We need to do further research to be sure, but these treatments are likely to have fewer, or different, side effects than standard chemotherapy.

She also found evidence that ependymoma cancer cells were over-reliant on two other amino acids, and that high-grade glioma cells relied on an amino acid called tryptophan and further work is ongoing to understand how we can target these to develop new treatments. However, both ependymoma and paediatric high-grade glioma brain tumours turned out to have problems recycling arginine.

Madhumita said: “I think that we’re only five to seven years away from developing a clinical trial for this treatment, based on similar research.

My team has identified two amino acid vulnerabilities each in paediatric high-grade glioma and ependymoma. We are now in discussions with drug developers to see whether we can test drugs in the lab to see how good they are at controlling tumour growth.”

Madhumita and her colleagues, Donald Macarthur and Richard Grundy.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG