One of the top priorities for childhood cancer research is understanding what causes cancer and how. We know that cancer happens when the working of cells ‘goes wrong’ – and that this is normally due to an error or change in the cell’s genetic code. These genetic can happen (most commonly for childhood cancer) accidentally as the cell goes about its usual business. Our genetic code is around three billion units long and is copied around two trillion times a day. This means there are lots of opportunities for things to go wrong, like the code being copied incorrectly. In a proportion of cases, a predisposition to cancer might result from a child inheriting a faulty gene from one parent or other.

Although important more generally across all age groups, cancer can be caused by things in the environment damaging the DNA (like the carcinogens in cigarette smoke), but environmental factors are rarely the cause of childhood cancers.

Unsurprisingly, our cells have evolved to be pretty good at spotting errors and fixing them. There are lots of different ways this can happen, like enzymes that ‘proofread’ newly copied DNA and immune cells that looks out for cells that aren’t doing what they are supposed to.

Normally, a new change in just one gene isn’t enough to cause cancer in humans. Usually, around five to six genes need to be corrupted in order to cause cancer.

One of the things that make malignant rhabdoid tumours so unusual is that they are caused by just one gene failing to function normally. Malignant rhabdoid tumours (MRT) are a rare type of cancer that mostly affects very young children and usually grows in the kidneys or soft tissue, but can also arise within the brain where they are called atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumours.

What are researchers doing about it?

Professor Maureen O'Sullivan at Trinity College Dublin believes that the only way we can improve the outlook for children with MRT is by understanding more about them. Funded by CCLG and the Grace Kelly Childhood Cancer Trust, she has been working to understand how the changes in the one gene, called SMARCB1, lead to such a devastating cancer.

Professor Maureen O'Sullivan

Maureen said: “MRT is different in several ways from other cancers, because it normally occurs in very early childhood, particularly within the first year of life, and a patient might even be born with it. MRT is unusually aggressive and difficult to treat. Genetically, it’s remarkable, because it consistently shows DNA mutations in only one gene and also because about a third of patients are born with a genetic predisposition to MRT.

However, if they don’t develop the cancer by a certain age, that risk of getting MRT virtually disappears. This tells us that the genetics (or more importantly epigenetics) of really young children are somehow providing ‘fertile soil’ for this specific tumour. Therefore, my team and I really wanted to explore what was so significant about this particular gene.”

To find out more, Maureen’s team grew MRT cells, which don’t have a working copy of the SMARCB1 gene, in their lab. Using genetic engineering, they then ‘rescued’ the MRT cells by giving them a working copy of the gene. This meant that they could see what the differences were between cells that had SMARCB1 protein and those that didn’t.

What they found

The researchers’ work showed that the SMARCB1 protein, coded for by the SMARCB1 gene, is normally part of a larger complex (known as the BAF complex) of proteins that regulates how and when genes are expressed. Gene expression is complicated – there are so many processes happening inside your cells, and they need to happen in certain orders, at certain times, or in certain circumstances. Therefore, genes need to be controlled in terms of when to turn on (and be expressed) or to turn off by complexes like the BAF complex. This means that problems with the SMARCB1 gene leads to a huge number of other genes not being turned on and off correctly, causing lots of problems in the cell.

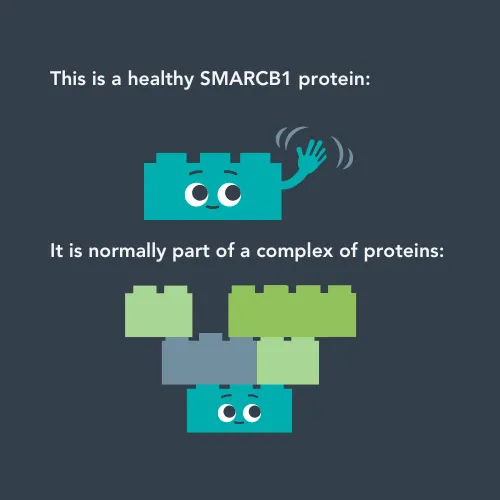

When the SMARCB1 gene works properly, it makes healthy SMARCB1 proteins. These proteins join up with other proteins to create a bigger structure called the BAF complex.

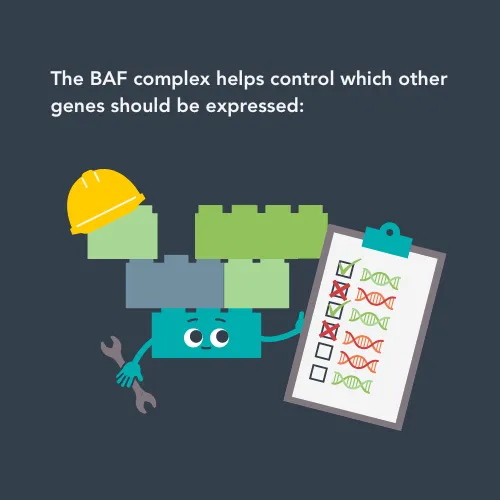

The BAF complex plays an important role in turning other genes on and off, which makes sure that cells operate properly.

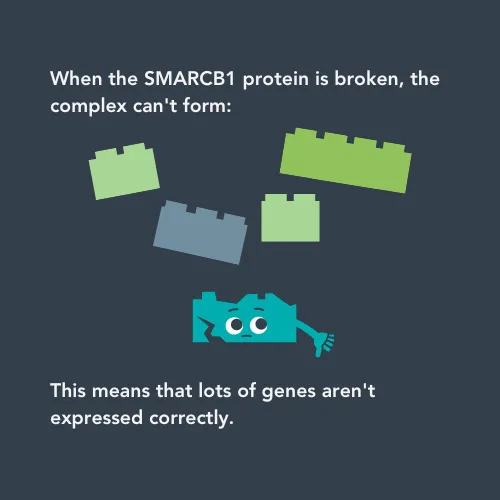

When the SMARCB1 gene isn’t working properly, the SMARCB1 protein can’t join the complex. This means lots of genes aren’t regulated properly, causing lots of problems for cells.

The team found that “the loss of the SMARCB1 protein causes DNA regulation problems at a global level, which has an impact on more than 1,300 genes. This explains how just the one gene being inactivated can have such a powerful effect without any additional genes actually being mutated.”

Another part of Maureen’s project has been trying to find what type of cell MRT starts in for the first time. The cancer can occur in lots of parts of the body – whilst it is normally in the kidneys, it can grow in any soft tissue, and can arise even in the brain (although it is known by different names in different parts of the body).

She said:

“Knowing what type of cell the SMARCB1 error first occurs in is important, especially for developing targeted chemotherapy treatments. It is also of great academic interest to find the likely cell of origin as MRT can occur in so many locations.”

Maureen found a primitive type of cell that they believe is the origin of MRT. These cells are a bit like stem cells and can specialise into other cell types like fat cells or connective tissue cells. Her team showed that the primitive cells had problems with DNA regulation, which led to them not maturing properly and instead becoming cancerous.

This project has now finished, but the impact of the team’s work continues. After publishing the results, research teams from Toronto and Dublin got in touch to collaborate on MRT research. This shows that this work has had an impact and will continue to drive progress forward for this rare and aggressive cancer.

Maureen said:

As with many ultra-rare cancers, there has been too little attention given to malignant rhabdoid tumours - even despite the poor patient outcomes. This means that any insights from our work could potentially have a big impact on our understanding of it and eventually for patients.

"My group focuses mainly on improving the understanding of malignant rhabdoid tumours, however we do also collaborate with a group here in Dublin who have expertise in targeting treatment resistance in cancer cells. That work takes a more pharmacological approach to investigating MRT and could be very important for the successful treatment of this cancer.”

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG