The term ‘childhood cancer research’ covers a wide range of the cancer journey, from how cancer starts in human cells to how long-term side effects of having had cancer as a child affect survivors many years later. When you start looking at childhood cancer research, not only is there medical jargon to understand. but also lots of different terms for the research projects themselves.

Generally, scientists don’t mean to be confusing. It’s just that, to other researchers or doctors in their field, using more complicated medical terms is the easiest way to explain a certain idea. For example, it’s quicker to say ‘refractory cancer’ than ‘cancer that has not improved with treatment’.

In recent years, there has been a big push for scientists to write ‘lay abstracts’, which are summaries of their projects that are written for anyone without a scientific or medical background. All of CCLG’s researchers write a lay abstract when they apply for funding. These are reviewed by our parent and patient interest group, which is made up of people who have experience of childhood cancer such as ex-patients and parents, and the feedback is shared with the researchers. We also continue to work with researchers throughout their projects to make sure their findings are shared in a way that’s accessible to everyone.

It’s quite difficult to switch from the hyper-focused and super detailed terminology needed for scientific papers and reports, to clear and simple language. But researchers really do want to make the effort, and value feedback. One of our researchers recently said:

The feedback was really eye opening. From the questions asked by the group, it was evident I had not made clear, in terms accessible to all, what it was we were trying to achieve. Having received this feedback, I now approach writing these sections in a different way. I have returned to this feedback time again to learn from it, and I also actively engage with parent and patient interest groups to ask for feedback prior to submitting grant applications.

What are the types of research?

One of the purposes of this blog is to ‘de-mystify’ science, so everyone can engage with it and become excited by the possibilities that research brings. So, I wanted to share with you some of the most common types of childhood cancer research, what they are, and give you some examples from our research projects.

Review

A ‘review’ involves reading all current published research on a particular topic, assessing the evidence and combining it to form a recommendation for healthcare professionals to use in clinical practice. This is normally one of the fastest project types, taking up to two years to complete.

Dr Jess Morgan works at the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at the University of York - a research centre that specialises in reviews. She is working on a review of whether blood and bone-marrow tests are helpful in diagnosing leukaemia relapses before symptoms are noticeable. It’s a systematic review, which means she will only include research papers that match strict criteria, such as being from certain locations or including specific data. Jess hopes her findings will help improve and standardise the follow-up care for children with leukaemia across the UK. Read more here.

Dr Jess Morgan

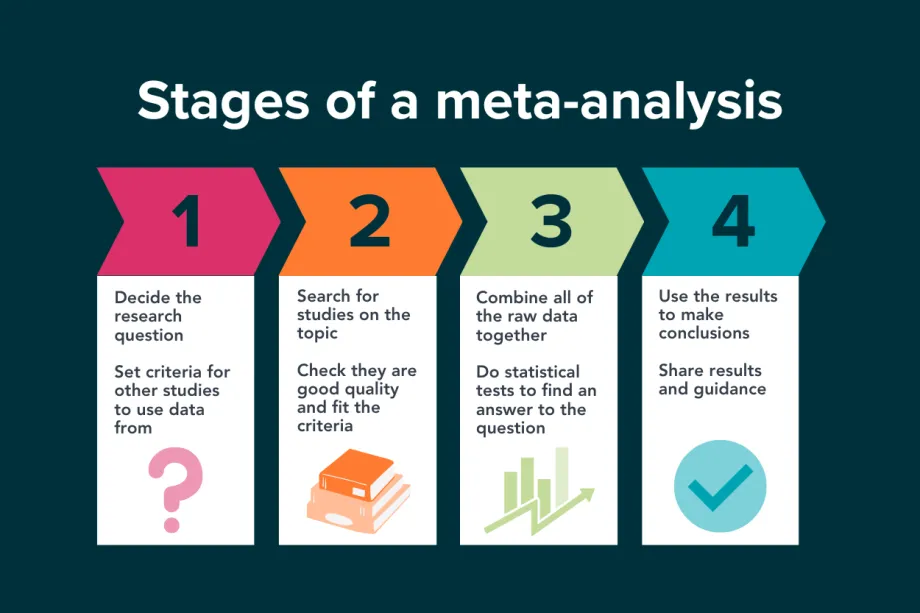

Meta-analysis

This involves taking the raw data from several existing relevant research papers, and doing statistical tests on them to find out what the overall results are. For example, this can help give researchers a clearer idea of the effects of a new medicine if there are lots of competing studies with different results. This type of project can take around two years, depending on what else it includes.

Dr Jess Morgan has completed a meta-analysis on whether follow-up scans, like X-rays or CT scans, improve the chance of diagnosing cancer that has come back after treatment. This project contains a systematic review to gather all of the relevant studies, and then Jess has done a meta-analysis which combines all of the data and results from the studies to create one big sample. She has then looked at the data in the sample to see whether different factors, like the age of the child or the type of cancer, mean that scans are more helpful or less helpful. She found that there wasn’t a significant difference to a child’s survival if they had follow-up scans or had relapses caught by showing symptoms, but there were exceptions and a lot of incomplete data. Read more here.

Qualitative

This type of study helps researchers understand people’s thoughts and feelings about things. This can help shape the information given to patients, parents, and doctors as a child goes through treatment. Qualitative projects take around two years.

Professor Linda Sharp, at Newcastle University, worked on a project that used qualitative methods to help promote the importance of physical activity for childhood cancer survivors. She has conducted in-depth interviews with childhood cancer survivors and parents to find out what they think about exercise and what is preventing them from doing it. Using this information, and with help from survivors and parents in workshops, she is now designing an intervention that will help childhood cancer survivors get active. Read more here.

Professor Linda Sharp

Translational

This term applies to any project that aims to get research from ‘bench to bedside’; taking findings from other projects and turning them into results which directly benefit patients. For example, this might be taking a project’s finding that a specific gene impacts tumour growth, and then building a treatment which targets this gene. This type of research is very diverse, so there is a big range of timescales, from around one to six years.

Dr Francis Mussai has created a new treatment that he hopes to take into clinical trials, and therefore to patients, soon. His ‘antibody smart-bomb’ primes the patient’s immune system so it can attack the cells that turn off other immunotherapy treatments and which stop the body using its natural defences against cancer cells. As the smart-bomb is already used to treat some patients with blood cancers, Francis and his team at University of Birmingham hope that it could be moved into a clinical setting quickly. Read more here.

Dr Francis Mussai

Non-clinical

This is a diverse group of projects that don’t directly involve patients and can also be called a few different names like basic science and fundamental research. They might be looking to uncover how cancer develops genetically, understand how cancer cells in a lab react to different medicines, or to investigate patient samples as case studies. If they are done before a clinical trial, the project might be called ‘pre-clinical’. These projects can take anywhere from one to six years.

In 2020, Dr Anestis Tsakiridis at the University of Sheffield completed a project that aimed to find out which type of cell causes childhood brain tumours. After identifying a type of stem cell that the team believes leads to other cancers, like neuroblastoma, they managed to develop a way of growing these cells in the lab so that future research can study the way these cells turn into cancer. Using the same methods, Anestis hopes to be able to find out how normal stem cells develop into brain cancer, and also to find out whether he can use the same methods to study adult brain tumours. Read more here.

Clinical trial

A trial is the first time a researcher uses humans to test their idea, so there are a lot of ethical approvals and evidence needed. Trials have four phases, and one research project might contain multiple phases or be testing multiple new treatments. You can find out more about the clinical trial process in CCLG’s Contact magazine. These tend to take around six or seven years per phase.

Early phase trial

This covers phases 1 and 2, which look to find out what the safe dosage of a new medicine is and whether the medicine can attack tumours as intended. These phases use very small groups of patients, and patients are often only asked to join when they have no other treatment options available.

Dr Carmela De Santo is running a Phase 2 clinical trial which is testing a new treatment for relapsed cancer, refractory cancer, and for rare immune conditions that can occur alongside childhood cancer. Both of these groups of children are very difficult to treat and there may not be many treatment options. Carmela’s team believe that all of these conditions could be treated by attacking specific immune cells, which have grown out of control and stop the immune system from properly attacking cancer cells. The team at the University of Birmingham are still recruiting patients for their study, which will test whether an existing medicine that targets these immune cells can improve a child’s chance of survival. Read more here.

Dr Carmela De Santo

Phase 3 trial

Phase 3 trials are all about finding out whether the new drug or treatment is better than current treatment options. They use big groups of patients and normally compare the outcomes of two groups of patients – one treated with the current best treatment and the other with the proposed new drug or treatment. If the trial shows the new treatment is better, and is approved by regulators, it will then become the new standard treatment for patients.

Also in Birmingham, Professor Keith Wheatley is running the largest Phase 3 clinical trial for liver cancer in children and young adults. This trial is so large that it works across 13 countries and is funded on a yearly basis rather than one funder paying for the entire project. The trial is testing six different treatment plans, such as new drug combinations and whether patients with less aggressive cancer could receive less treatment without affecting the chance of killing their cancer. The trial is ongoing, so we don’t have any results yet. Read more here.

Phase 4 trial

Phase 4 trials are also sometimes called post-marketing surveillance and monitor patients to make sure there are no long-term side effects or problems. It’s important to find out whether there are any side effects that weren’t noticed during the earlier clinical trial phases, and check that the treatment continues to work as intended further down the line. These trials include the biggest group of patients yet. We haven’t funded any Phase 4 trials yet, but who’s to say what the future holds?

What else do you need to know?

There are other types of research out there, and lots of other scientific words to describe them, but these are some of the main projects you’ll encounter.

It’s also worth remembering that a research project can be more than one type – for example, Jess’s project on scans includes a review and a meta-analysis, or Francis’ antibody ‘smart-bomb’ could also be considered pre-clinical as he hopes to move the treatment into a clinical trial next.

There you go – consider research project types ‘de-mystified’! If you have any questions about this blog (or any others) please feel free to tweet me @EllieW_CCLG

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG