All over the world, researchers are working hard to create a brighter future for children with cancer. In the UK and Ireland, over 100 of these researchers have been funded through CCLG.

We fund our own research, and we also support other charities to fund research through the CCLG Charity Research Funding Network. Our goal is to enable childhood cancer charities to fund the research that is important to them, but with the support of our rigorous and accredited research process and our specialist expertise. This makes sure that funding is used for high quality research that is likely to have a real impact.

But what does this impact look like? Let’s take a trip to London, where the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is based. This is the research side of the famous Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), one of Europe's biggest childhood research institutions. Let’s find out about three of the projects we have been involved in funding there…

Improving treatment decisions and outcomes in low grade glioma with Professor Darren Hargrave

Darren works on a type of brain tumour called paediatric low-grade glioma (PLGGs), which can affect any part of the brain and spine. It can be very treatable but often comes back. Patients need multiple rounds of treatment, and this can damage children's developing bodies and brains. This risk makes it tricky for doctors to know the key factors when deciding which treatments to give.

Professor Darren Hargrave

In his CCLG project, Darren wants to produce guidelines to assist doctors and families with informed treatment decisions. Guidelines would help doctors make the right choice for their patients, based on what is important to them and their families. The project is funded by a CCLG Special Named Fund called Thomas’ Fund, set up in memory of 4-year-old Thomas, who passed away from PLGG in 2015.

In order to understand which factors affect patient survival and quality of life, Darren’s team has analysed the records of over 1000 PLGG patients treated at GOSH. Around 450 of these patients have consented to sharing their tumour samples too, so the researchers should be able to link tiny changes in the tumours with different outcomes. For example, the team might find genetic or biological differences that are linked to more relapses, or to the cancer being harder to treat.

However, treatment decisions are not solely based on the facts and figures found in medical reports. The side effects patients experience during and after treatment can have a significant impact on a child’s quality of life. To capture the full scope of treatment and survivorship, Darren’s team worked with a group of PLGG patients and parents to develop questionnaires for families who had recent experience of treatment.

The research team is now busy analysing the tumour samples and collecting data about the important quality of life measures. This information will be combined to create the guidelines, and a predictive model. Darren hopes the model will be able to predict the potential outcomes of different treatment options, providing patients with the best treatments possible.

'Getting it right first time' for children with renal tumours with Dr Tanzina Chowdhury and Professor Kathy Pritchard-Jones

Every year, 1,000 children are diagnosed with kidney cancer in Europe. Whilst they can be treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, treatment doesn’t always work. Treatment carries the risk of lifelong side effects, like liver damage and heart problems. Sometimes, children cannot be cured.

Tanzina and Kathy’s project, funded by The Little Princess Trust, aimed to improve survival rates and quality of life for survivors. It had two goals, to improve diagnosis quality and to improve the healthcare service.

Professor Kathy Pritchard-Jones

To improve diagnosis, doctors needed to know more about their patients from the start. The researcher team set up an expert service that reviewed every patient's MRI and CT scans at diagnosis. The experts looked for any changes or signs that more intense treatments were needed. Nearly all the specialist treatment centres in the UK and Ireland joined the study and had access to this expert support.

Tanzina and Kathy's team also examined kidney tumour samples for any biological markers that could predict whether the cancer would be high-risk. If they could identify reliable markers, it could help doctors know which patients need more treatment from the start.

As part of improving the healthcare service, this project also supported the development of an ongoing national renal tumour advisory panel. This group of kidney cancer experts helps doctors with difficult cases and has impacted over 190 children’s treatment so far.

This project has contributed to a lot of other research and related work is still ongoing. Tanzina is also continuing her work in kidney cancer care improvement. Altogether, this project will continue to benefit children with kidney cancer long into the future.

Creating a new combination treatment for children's brain tumours with Professor John Anderson

Brain tumours can be hard to treat – especially in children. Doctors have to get toxic medicines into the brain – the most well-protected and important part of the body. However, chemotherapy can cause lasting damage to children’s developing brains because it harms healthy cells as well as cancer cells. Sadly, there often are no better options for many young patients.

John is developing a treatment that uses the immune system to specifically target brain cancer cells. Immunotherapy is an exciting new cancer treatment that can cause less damage to healthy cells - but it is mostly not available for solid tumours like brain cancer yet.

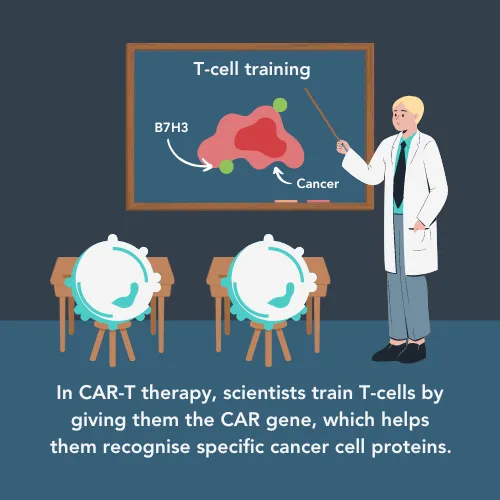

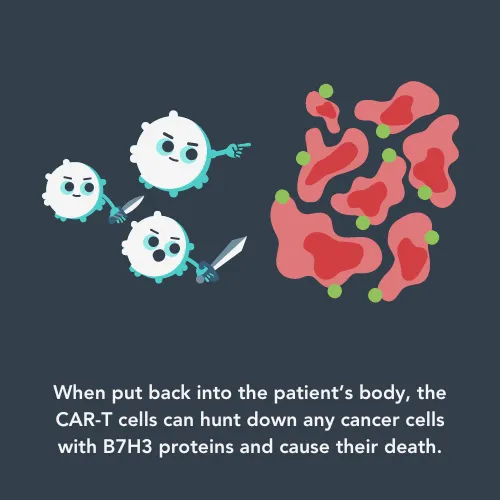

John’s team is using a type of immunotherapy called CAR-T cell therapy. In this type of treatment, doctors train a patient’s own immune cells, called T-cells, to hunt down cancer cells based on proteins on their surfaces. John's CAR-T cells can target brain cancer cells with a protein called B7H3. When the CAR-T cell encounters a cancer cell with the B7H3 protein, it activates processes to kill the cancer cell.

Researchers think that one of the reasons CAR-T therapy isn’t as effective in solid tumours is because the CAR-T cells become ‘exhausted’. So, John has designed his treatment to have an off switch, triggered by medicines called ‘immunomodulatory drugs’ (IMiDs). This allows the CAR-T cells to be switched off for short breaks to rest and recover.

In his Little Princess Trust-funded project, John is testing the combination treatment. He is looking at whether forcing the CAR-T cells to take breaks with the IMiDs allows them to come back stronger and fight cancer for longer. He hopes to find the best doses and schedules that keep the CAR-T cells fighting fit, and to make sure the combination is an effective treatment.

In the first year of their project, John’s team has been working hard to prepare the cancer cells, genetically engineered immune cells, and drugs needed. Because of their amazing work so far, the researchers have already secured funding for future clinical trials. Therefore, by the end of this project in 2026, this treatment could be offered to children with brain tumours in a Phase II clinical trial.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG