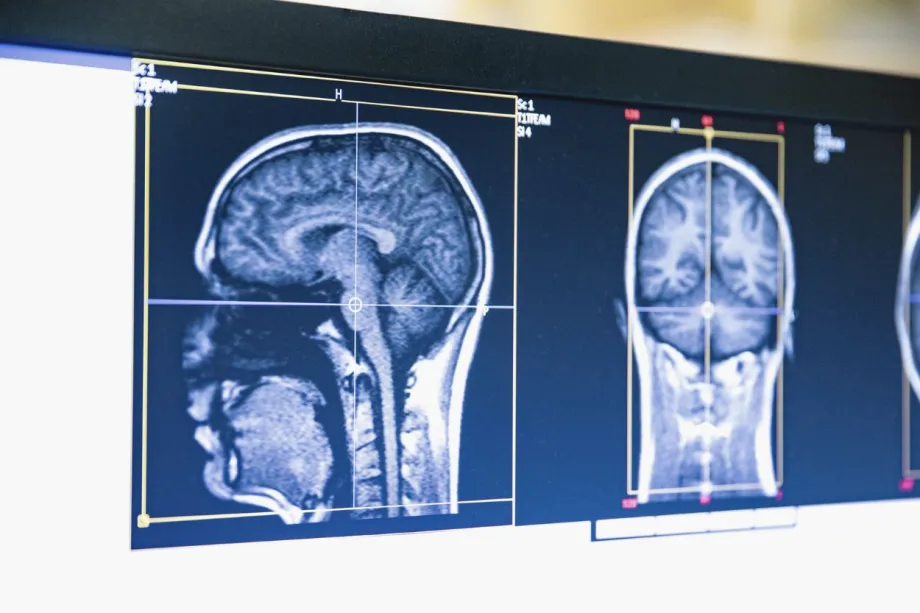

The last week of October each year is Brain Tumour Awareness Week, so let’s take a closer look at the brain and how it works! Brains are, understandably, very complicated. Whilst your brain is busy reading this, it’s also regulating your breathing, making sure the right enzymes are released to digest your food, and trying to keep your body at the correct temperature. And that’s only a few of its jobs.

As brains are so complicated, it makes sense that brain tumours are hard to treat. There’s a lot of consideration needed because the impact of cancer and treatment on the brain can be significant, with higher risks of long-term side effects.

When we look at children’s brain tumours, it’s even more difficult. Doctors still have to remove the tumour but also need to allow the child’s brain to carry on growing and developing without harming it. Brain tumours are the most common type of solid cancer in children, but still have few successful treatments. Read on to learn more about the brain, the challenges of childhood brain tumours, and to learn about a very unusual research project.

Starting with the facts

- The brain uses about 20% of the body's oxygen and energy, even though it only accounts for around 2% of your body’s weight. Researchers think that this is because the brain is constantly active and needs to be kept in a ‘ready’ state in order to have speedy reactions and processing.

- The left and right sides of the brain look pretty much the same but actually have very different roles. The left side is more computer-like, looking after your analytical thinking and maths, while the right side is more creative and looks after your imagination and artistic side. They have other functions too, and work together to make you, you.

- Did you know that the brain has its own protection? The blood-brain barrier is a network of tightly-packed cells surrounding the blood vessels that go to the brain. This is intended to only let ‘safe’ things through to the brain, like water or oxygen, but some bacteria and viruses have evolved to sneak past the blood-brain barrier. Most chemotherapy drugs can’t get through, which can be a big barrier to treating brain tumours.

- The brain doesn’t finish developing until you are in your 20s! Researchers have found that this includes the frontal lobe, which is responsible for decision-making and impulse control, and affects the connections inside your brain which make your brain more specialised. However, we don’t know exactly what effect this all has on a young person’s behaviour or choices.

- Did you know that your brain cells produce electricity – enough to power a lightbulb? One of the ways that brain cells communicate with each other is by sending electrical impulses. Some researchers have even found that giving tiny electric charges to the brain can help treat stress and improve memory – changing the electricity in brain cells can change how the brain works.

Brains are complicated

These facts show just how complex the brain is – and that’s before adding a brain tumour into the mix. Some of the unique features of the brain, like the blood brain barrier, actually make it a lot more difficult to treat brain tumours, because chemotherapy medicines can’t get to the tumour.

Children and young people’s brain tumours are even more difficult as the brain is still growing and developing so the toxic chemotherapy needed to kill cancer may cause too many problems for the patient. Even when treatment is successful, patients can be left with serious side effects such as cognitive and learning difficulties, memory loss and personality changes that can affect their daily lives.

It’s clear that we need safer and kinder treatments for childhood brain tumours. CCLG have funded 37 research projects into brain and spinal cord tumours, some in partnership with the Little Princess Trust, of which 21 are working on new or improved treatments.

An unusual project

An unusual project, funded by the Little Princess Trust in partnership with CCLG, is by Dr Stuart Smith. When his team realised that a lot of the genes associated with brain tumours were related to cancer cell’s electrical activity, he wanted to find out how electricity could help children with brain tumours.

Dr Stuart Smith

He said: "It was really exciting when we first looked at the genomic data for childhood brain tumour cells and realised that many of the key genes involved seemed to be involved with electrical processes in the cell. We then started to consider this as a potential avenue for treatments."

Electrotherapy (the use of electricity as a treatment) is already used for adults with brain or spinal cord tumours. Patients shave their heads and wear a special device most of the day, which generates small amounts of electricity to affect the brain cancer cells.

Stuart said:

Some childhood brain tumours remain incurable with very poor survival rates. We need new approaches, and changing the electrical fields within tumours is a completely new way of slowing tumour growth. However, current electrotherapy needs to be optimised for the unique nature of childhood brain tumours and made more child friendly.

This is why he started to work on some of the most common childhood brain tumours, such as high grade glioma and ependymoma, which don’t have many successful treatment options.

With Dr Ruman Rahman in the lab.

Where do you start?

The first step was for the research team, based at the University of Nottingham, to find out which proteins are part of cancer cells’ electrical activity. A type of protein called an ion channel allows tiny charged particles, called ions, into and out of the cell. This means that ion channels play a big role in a cell’s electrical activity as they can control how many of these electrically charged ions are in the cell at any one time.

The researchers narrowed it down to two ion channels, called CLIC1 and CLIC4, that they believe are overactive in a few childhood brain tumours. As the tumour cells need the electricity to grow and encroach on healthy brain tissue, blocking the ion channels could help stop brain tumours from growing.

Stuart explained:

CLIC channels serve many functions in cells, allowing cancer cells to change shape and invade into normal brain but they also have this extraordinary effect on the electrical field that exists in every living cell. By producing more CLIC channels, we think cancer cells can speed up their growth.

When his research team looked at tumour samples from patients, they found that there were often too many of these ion channels in the cancer cells, which was linked to a lower chance of survival.

A new type of electrotherapy

Stuart knew that electrotherapy in its current form would not work for children. However, there is always more than one way to do something, and his team believes that blocking the cell’s ion channels with medicines, either instead of or in addition to dosing the brain with electricity, could work.

Stuart in srugery.

They have already found a medicine that could work, and are now gathering the data that is needed in order to move the treatment into a clinical trial where it could directly help patients.

Stuart’s project will end next month, but his team have already been funded by an American cancer charity to continue their valuable work.

Stuart said:

The funding from The Little Princess Trust, in partnership with CCLG, has allowed us for the first time to clearly show that manipulating the electrical field in childhood brain tumour cells can slow their growth and invasion. The project allowed sophisticated electrical recordings of living cells, which showed the role CLIC channels have in producing the living electrical field that keeps cancer cells alive.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG