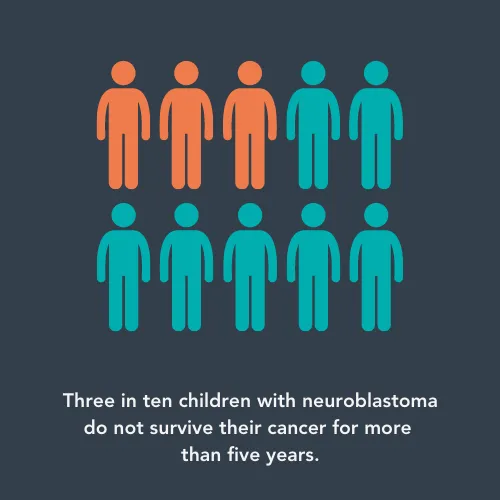

Neuroblastoma is a type of cancer that mostly affects children under the age of five. It is one of the more common childhood cancers, which means that it is sometimes easier to research than rarer cancers as more patients per year are diagnosed. Years of research have contributed to an overall five-year survival rate of around 70%. This means that, five years after diagnosis, seven out of ten children with neuroblastoma will still be alive.

This is a fantastic improvement from around 40% survival in the 1980s. However, it is below the overall survival rate for all childhood cancers combined, which is 85%. This shows that there is a need to understand more about this cancer – but do all children with neuroblastoma need new treatments?

Doctors allocate children with cancer to risk groups to help decide how intensive their treatment will need to be to fight the cancer. Neuroblastoma is usually grouped into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups.

That average 70% survival rate is very different between risk groups. Children with low-risk neuroblastoma have an amazing survival rate of over 90%. These patients can normally be treated successfully with standard treatments like radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, the same treatments might not work for high-risk patients. It turns out that overall survival rate is hiding an important fact: only half of children with high-risk neuroblastoma will still be alive after five years.

New treatments

Dr Alexander Davies, at the University of Oxford, is one of the legions of researchers working hard to improve the outlook for children with high-risk neuroblastoma. He’s working on a non-standard type of treatment called antibody immunotherapy.

Dr Alexander Davies

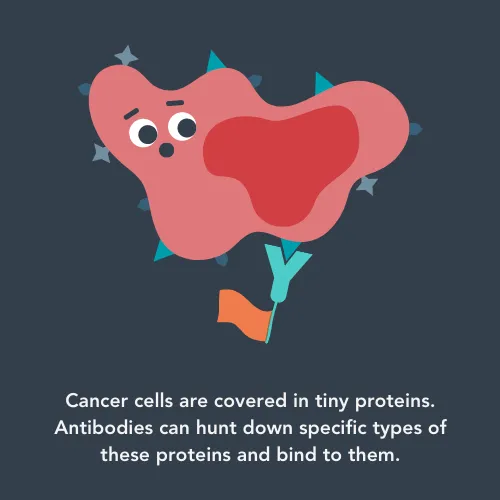

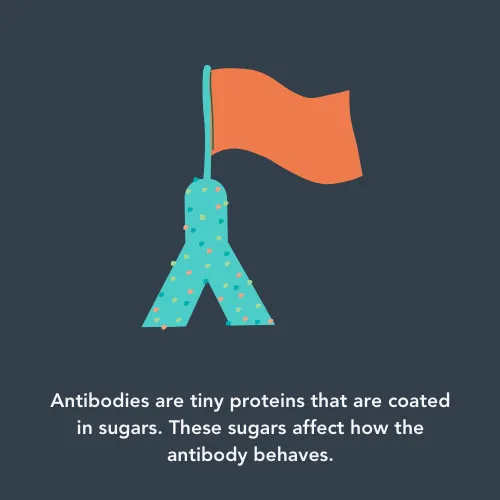

This type of treatment uses a child’s own immune system to fight cancer where the lab-made antibodies (tiny proteins that can hunt down cancer cells based on the proteins on their surfaces) trigger or help the immune system to attack the cancer cell they are bound to.

Whilst immunotherapy is targeted towards cancer cells, causing less damage to healthy cells, there are still serious side effects. The main issues for children with neuroblastoma receiving antibody immunotherapy is nerve pain and damage, which can be so bad that a child needs to stop treatment and can last years after treatment.

Alexander, funded by The Little Princess Trust, has been trying to find out why the antibodies cause these side effects, and how to prevent them. He said:

Currently, patients face the choice of effective, but excruciating, immunotherapy or finding an alternative treatment. As we get better at treating cancer, we need to pay more attention to the side effects of treatment - alleviating pain is a key part of improving treatment success and ensuring quality of life for survivors.

He is looking at a specific part of the antibodies – the sugar coating. These tiny pieces of sugar can decide how the antibody behaves when it finds a cancer cell, such as whether it attracts other immune system cells or not. Alexander believes that changing these sugars might help reduce the pain and nerve damage caused by the antibodies.

Sweet success

Once the researchers developed a way to remove the sugar from the antibodies, they were ready to test whether this caused less damage to nerve cells. To find the answer, Alexander’s team grew human nerve cells from stem cells in their lab. This meant that they could have a more accurate idea of how the modified antibody behaved in humans, rather than animals which are normally used at this stage.

Alexander said: “We are applying cutting edge antibody and human stem cell culture technology to understand what immunotherapies do to the nervous system and to bridge the gap between the lab bench and the patient bedside.

“By using stem cell technology to create human sensory nerve cells to test the new antibodies we aim to make our findings as relevant to patients as possible.”

His team found that removing most of the sugar on the antibodies is a lot less toxic for these lab-grown nerve cells. With only a couple of months remaining on their project, the researchers are now checking whether the new antibody can still lead to cancer cell death.

Getting glittery

Now Alexander’s project is reaching its end, his team has been sharing what they have been up to. They have plans to publish scientific papers, and have shared their project at conferences, where their research will reach and inspire fellow scientists. However, they also wanted to share their work with people who didn’t know about childhood cancer research, by taking part in Freeland School Science Day.

Freeland School Science Day

Talking about why his team took part in the science day, Alexander explained:

Children have a natural curiosity – the very thing that drives even the most senior scientists! They also often see things in a way that gives you a completely new perspective on your work.

His research team joined forces with Simon Rinaldi’s lab to create an exciting activity to teach children about their work. The goal was to help pupils understand how the scientists can see antibodies in the lab.

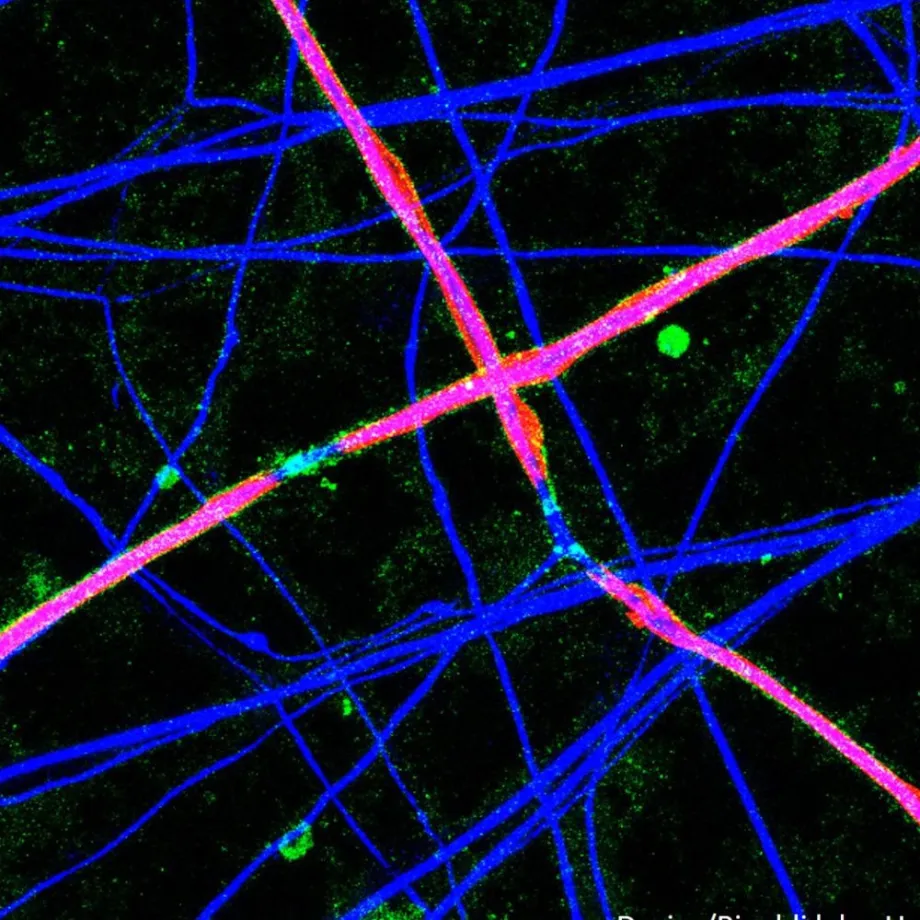

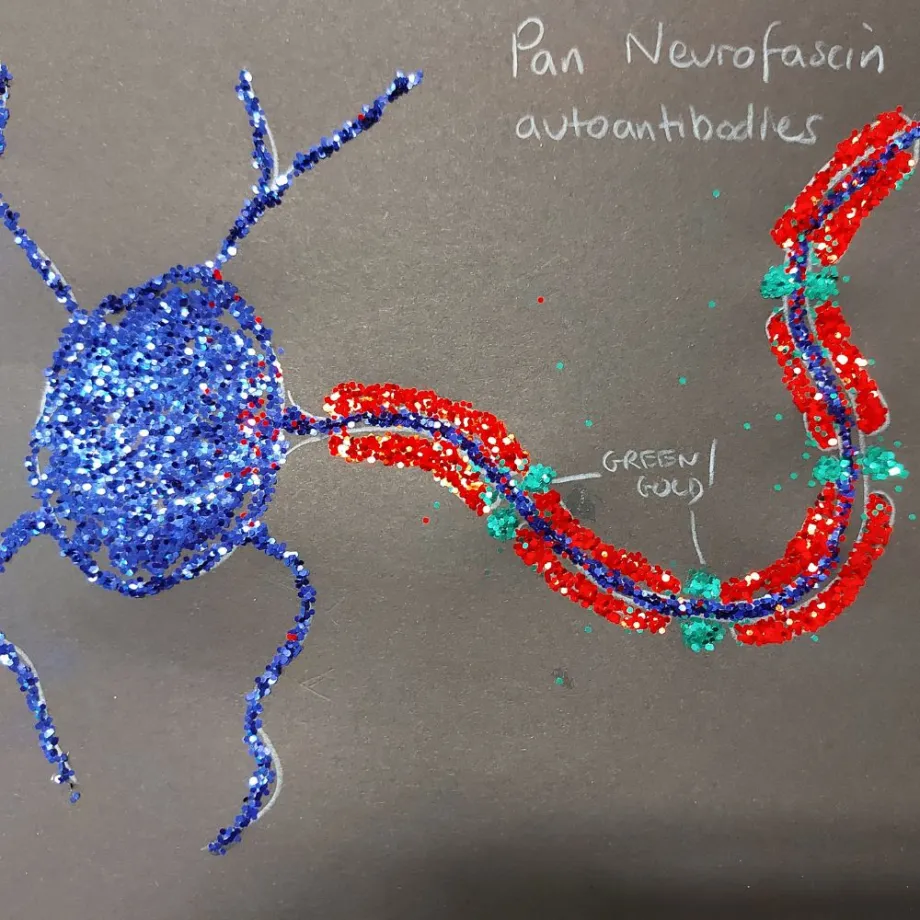

The children were shown images of real nerve cells, which they then drew out on card. They used clear glue to represent the antibodies used in the lab, which showed how they are hard to see in the lab. They then added glitter to show how researchers add tiny fluorescent probes to antibodies in the lab, allowing the antibodies to be seen through the microscope.

The nerve cells covered in fluorescently tagged antibodies.

Alexander said: “The children loved being creative with the glue and glitter – and being a bit messy in the classroom! They were also fascinated to learn about antibodies, nerves and how they work.”

Activities like this help engage children in science, building their confidence and understanding of complicated topics. By the end of the Science Day, the children understood scientific words like neuron and antibody. Perhaps one of the Freeland School pupils will be part of the next generation of childhood cancer researchers? Only time will tell…

One of the nerve cell drawings with glitter to mimic antibodies.

Science is done as part of a team. The Davies lab would like to acknowledge the work of their collaborators on this project: Dr Simon Rinaldi (University of Oxford), Professor Ben Davis (Rosalind Franklin Institute) and Dr Juliet Gray (University of Southampton).

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG