Hospitals can be big scary places, and they can be particularly hard to navigate when you are thrown into the world of cancer care after a shock diagnosis. Knowing what to expect, and what your child is entitled to, can be difficult.

The World Health Organisation has developed a rapid assessment checklist called ‘Children’s rights in hospital’, based on the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to make sure children’s rights are protected in hospitals. The checks go through seven key rights and cover how hospitals should be assessing them.

In this blog, we’ll go through a whistlestop tour of these rights. We’ll look at the elements that are important for children with cancer, and see how these are being assessed, improved, and managed. Read on to find out more!

The right to quality services

In the UK, all children with cancer are treated at Principal Treatment Centres, which specialise in treating childhood cancer. This means that children are getting expert care that is designed for young people. All of these hospitals will also take part in research to some extent, whether working on their own projects or working with clinical trials to bring the best new treatments to patients.

An important part of developing and maintaining quality services is training. In December, CCLG launched a new free training course, designed for people new to working with children and young people with cancer. This will help improve cancer care knowledge across the UK, train overseas cancer professionals, and give people the tools they need to excel in caring for people with cancer.

We also have researchers working hard to improve treatment guidelines and find the best treatments for children with cancer.

Professor Gareth Veal

Professor Gareth Veal

Optimising drug treatment for childhood cancer patients

Professor Gareth Veal used a technique called therapeutic drug monitoring to make sure over 150 babies received safe and effective amounts of chemotherapy, and developed guidelines to improve care for very young children going forward.

Dr Jess Morgan

Dr Jess Morgan

Are regular blood and bone marrow tests helpful after childhood leukaemia?

Dr Jess Morgan is looking at whether follow-up tests are able to detect relapsed leukaemia before a child shows symptoms, and whether this increases their survival. As follow-up tests cause significant anxiety for patients and families, it is important to make sure they are beneficial. This project could help standardise and improve follow-up care.

Professor Juliet Gray

Professor Juliet Gray

Developing a kinder and more effective immunotherapy for neuroblastoma

Professor Juliet Gray wants to develop a safer and more effective type of immunotherapy for children with neuroblastoma. She is modifying a current immunotherapy so that it targets cancer cells better, without causing nerve damage and pain. She hopes that her new treatment will lead to fewer side effects and more children being cured.

The right to equality and non-discrimination

A key part of ensuring equality, equity and non-discrimination is to continually assess problems, so that you can address any issues that arise. Whilst the NHS has policies in place to ensure equality and prevent discrimination, it also is constantly trying to improve.

The NHS Cancer Experience of Care Improvement Collaborative program assesses patients’ feedback annually, and aims to make improvements to patients’ experiences of cancer care.

Over the past year, CCLG Chief Nurse Jeanette Hawkins has been working on a project as part of this program to find out what support children with autism and learning difficulties need in order to cope with X-rays better.

Jeanette said:

We want every child and young person to be assessed prior to an x-ray to make sure any additional needs are met and communicated properly. The goal is to make sure children, young people, and their caregivers don’t experience unnecessary distress from a procedure that is a frequent and common part of cancer care.

Find out more about her quality improvement project in a previous blog post.

The right to play and learning

Most people know that there are teachers in hospitals who try to keep sick children up to date with their schooling. This not only makes sure that patients don’t end up at a disadvantage at school because of their illness, it also provides a much-needed sense of routine and familiarity.

You may not have heard of hospital play specialists, which have been recommended on children’s wards by The Department of Health and Social Security since the late 1970s. Their job isn’t just about the children having fun. Play can help distract children from unpleasant procedures, or make them feel more confident in the strange hospital environment. It can also be a way for them to process their thoughts and feelings about negative experiences, making them more resilient.

Penelope Hart-Spencer with a patient.

Penelope Hart-Spencer, a health play specialist at The Christie Hospital, told us:

As health play specialists, we use a wide variety of age-appropriate play resources to help children make sense of their diagnosis and treatment pathways. We use role play and imaginative play with action figures and dolls to demonstrate what happens during clinical procedures such as scans and blood tests. We use therapeutic and specialised play techniques to explore thoughts and feelings and help children to learn about the different clinical procedures they require.

Being playful with clinical instruments, such as turning a syringe into a water gun, or playing in a clinical environment such as a CT scanner room, desensitises children to the equipment and allows them to explore and become familiar and less fearful.

The right to safety and environment

Play is also part of children’s right to an appropriate environment, for example, making sure that waiting areas are child friendly and there are play areas. Luckily, most of the Principal Treatment Centres that look after children with cancer are dedicated children’s hospitals and are therefore designed to meet their needs. In the few that are not exclusive to children, there are excellent dedicated children’s cancer wards. Hospitals usually also allow a parent to stay with their child, which can help children feel safer and more comfortable.

Hospitals are also always trying to improve and give children and families lots of opportunities to give feedback about the care they have received. This can highlight whether there are issues like inadequate food for children or carers, poor accessibility, or if improvements are needed in the ward’s cleaning.

The right to information and participation

Whilst parents lead on most of the decisions during a child’s cancer treatment, it is important that the patient is able to understand what is happening and why. Hospitals should be able to provide age-appropriate information for children, train their staff in how best to talk to young patients, and give children and families plenty of opportunities to ask questions.

Understanding what will happen, for example, during treatment or a procedure like an X-ray, can make the experience less overwhelming and scary for a child. This means they will likely cope better with any uncomfortable situations, because they know why it is happening and when it will end.

Secondly, whilst a child cannot legally consent to tests and procedures, they can usually still assent to them if given age-appropriate information. This isn’t legally binding like consent is, but it means that they are agreeing to take part. This can change how a child feels about their treatment, both whilst it’s happening and when they look back on it.

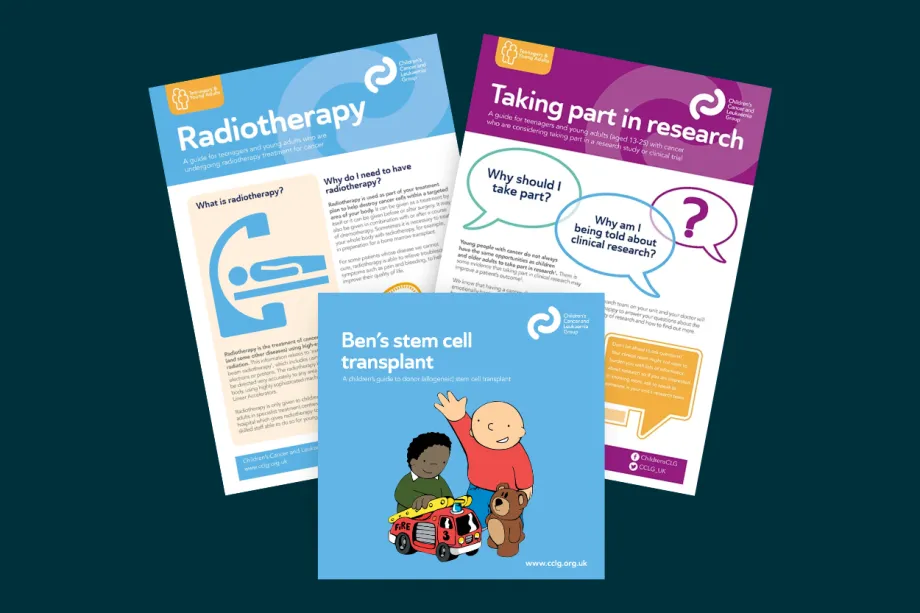

We produce a range of leaflets and factsheets, such as ‘Ben’s stem cell transplant’, which doctors and parents can use to help children understand their treatment and what it means. We also produce information for teenagers and young adults.

The right to protection

Providing accessible information is also an important part of making sure young people are protected. Asking for assent or informed consent (where able) ensures patients aren’t being pressured into a situation that is not to their benefit.

In terms of research, protection starts well before the stage of asking children to agree to tests or take part in a clinical trial. All research that involves people has to be approved by an ethics committee. The committee’s job is to ensure that anyone participating in the clinical trial is safe, that the planned research is worthwhile, and that there is enough scientific background to show that there is a potential benefit to patients.

The right to pain management and palliative care

Cancer care is not just about the treatments that kill cancer cells, like chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgery. There’s a lot more to a child than their cancer. It’s really important to manage their side effects, symptoms, mental health and welfare needs alongside cancer treatment.

Palliative care is often thought of as end of life care – but this is not always the case. Instead, its main goal is to help children with their physical and mental symptoms and improve quality of life for patients and families. The World Health Organisation recommend that palliative care starts as soon as a child is diagnosed with an illness.

However, the negative connotations that come with palliative care can make this distressing to patients and families, as they may feel that this means their child won’t get better.

Supportive care is very similar to palliative care, and some places use palliative care and supportive care interchangeably. It included preventing or managing side effects, managing pain, and making sure that children have the best life possible during and after treatment.

Most childhood cancer research focuses on new treatments, or understanding how cancer develops. However, one in three children who have died with cancer die because of the side effects of the treatment – not the actual cancer. Supportive care could help change this, but it is a very under-researched and under-resourced field.

This year, we were delighted to support Candlelighters in launching The Candlelighter’s Supportive Care Centre. The new centre will allow dedicated, expert research that could make a huge difference for children with cancer.

Why children’s rights matter

Children with cancer often have to stay in hospital for long periods of time which means the environment and services within each hospital play an important part of their cancer experience. Whilst we can’t change a diagnosis, we can make sure children’s rights are protected. Children with cancer and their families will therefore feel more supported and cared for during their hospital experience, which will likely have a positive impact on their emotional wellbeing, both during and after treatment.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG