All over the world, many researchers are working tremendously hard to create a brighter future for children with cancer. In the UK and Ireland, over 100 of these researchers have been funded through CCLG.

We fund our own research, and we also support other charities to fund research through the CCLG Charity Research Funding Network. Our goal is to enable childhood cancer charities to fund the research that is important to them, with the support of our rigorous and accredited research process and our specialist expertise. This makes sure that funding is used for high quality research that is likely to have a real impact.

But what does this impact look like? Let’s take a trip to Southampton to find out about two of the projects we have been involved in funding there…

'Do National Advisory Panels improve outcomes for patients?' with Dr Jessica Bate

Doctors may not see rarer types of cancer very often. This can mean that clinical teams at a main hospital might not know the best way to treat children with rare or relapsed cancers.

This is when they need to ask for help from a National Advisory Panel (NAP), a diverse group of childhood cancer experts who volunteer their time. Doctors can ask for advice about patients with rare or more complicated cancers and the NAP can debate the best treatment options from their extensive experience.

Dr Jessica Bate

Dr Jessica Bate works at University Hospital Southampton and was funded by CCLG to investigate the impact of NAPs. With her colleague, Dr Sarah Brown, she spent four years studying the panels. She wanted to see what impact their advice had on patients, whether they helped support doctors, and what they could improve on.

Jessica said:

We looked at 920 existing referrals made to six NAPs, who have all discussed hundreds of cases. The evaluation highlighted the time and effort that NAP panel membership entails and the impact the panels have on the management of patients.

The experts helped doctors with initial treatment options and options when the cancer came back, as well as deciding how high-risk the cancer was. Jessica found that doctors followed the expert advice around 90% of the time, and the most common reason for not following advice was due to patients or families wanting different treatments.

Working with parents, patients, and panel members focus groups, Jessica and Sarah created best practice guidelines for NAPs. This included adding fields to the referral form like whether the patient or their parents were hoping for a particular result or to avoid a certain treatment.

The guidelines also set out ways the panels could improve and streamline their process. One change suggested was for NAPs to set out how their panel works and can help patients, so that doctors know whether they are the right people to ask for advice. Other improvements were making sure enough members attend meetings to give a fully debated treatment plan, giving training opportunities for junior doctors and nurses, and making sure that the doctor asking for advice has met the patient and can present their views and wishes properly.

Jessica and Sarah hope that these guidelines will allow NAPs to work more effectively, leading to improvements for children with cancer.

'Helping to develop research into antibody treatment' with Dr Alistair Easton

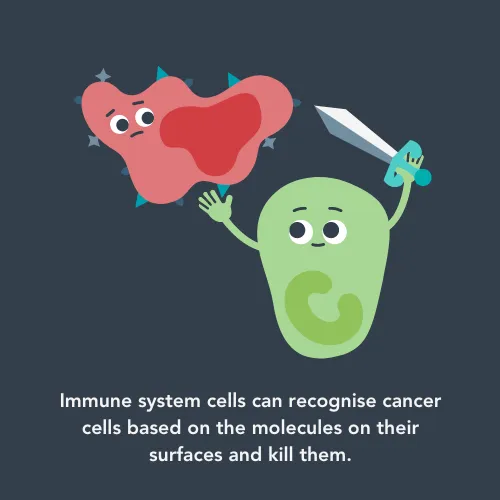

Our cells are covered with different molecules, like tiny proteins and sugars. These molecules can help cells communicate with each other and identify themselves to the immune system.

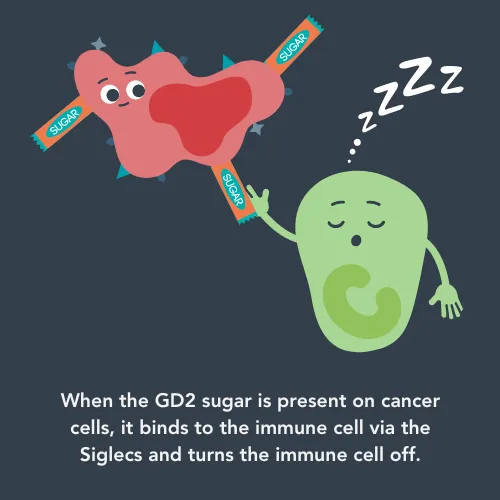

Cancer cells can have different molecules from healthy cells. For example, many aggressive childhood cancers express special sugars on their surfaces called gangliosides. One type of ganglioside is called GD2, and Alistair’s team at the University of Southampton have found that this sugar can stop the immune system cells from killing cancer cells. They believe this happens because the cancer cell’s GD2 can bind to proteins on the surface of immune system cells called Siglecs.

In his CCLG-funded project, Alistair wanted to find out whether there were any Siglecs on the immune cells found in neuroblastoma tumours. He hoped to prove whether cancer cells could bind to immune cells, and how that happens.

Alistair’s project finished in 2020 and successfully showed that Siglecs are present on immune cells within tumours. This provided evidence to support the development of treatments that target Siglecs, preventing cancer cells from turning off the immune system. He also showed which types of immune cells were present, and how these change before and after treatment.

Alistair said: "We were able to show that several different types of Siglec are found in neuroblastomas and are expressed by several different types of immune cell. Surprisingly, some immune receptors are expressed by the neuroblastoma cells themselves."

In addition, we discovered that there is huge variability in the immune system’s response to neuroblastoma and that the immune response that happens when the neuroblastoma vanishes without treatment has some unique features.

Alistair hopes further research will help identify the most effective immune responses against cancer and develop treatments to allow the immune system to fight cancer cells effectively.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG