All over the world, many researchers are working tremendously hard to create a brighter future for children with cancer. In the UK and Ireland, over 100 of these researchers have been funded through CCLG.

We fund our own research, and we also support other charities to fund research through the CCLG Charity Research Funding Network. Our goal is to enable childhood cancer charities to fund the research that is important to them, but with the support of our rigorous and accredited research process and our specialist expertise. This makes sure that funding is used for high quality research that is likely to have a real impact.

But what does this impact look like? Let’s take a trip to Manchester to find out about two of the projects we have been involved in funding there…

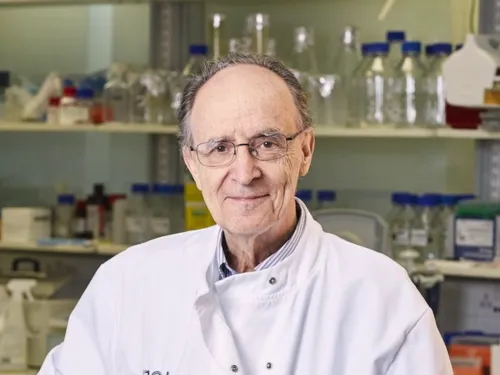

Improving bone marrow transplant for patients with high-risk leukaemia with Professor Rob Wynn

One treatment used for children with leukaemia is a stem cell transplant, which gives a patient new healthy stem cells from a donor. Stem cells are made by your bone marrow (the spongy bit found in the middle of some bones) and can develop into different types of healthy blood cells. This treatment can help a child recover from radiotherapy and chemotherapy and make sure they have enough blood and immune cells, or even reset the immune system so that it remembers to attack the leukaemia cells.

Professor Rob Wynn

Rob is a consultant for children with blood cancer at Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, where he has been working to improve treatment for his patients. He noticed that a particular type of stem cell transplant which comes from donated umbilical cords was more effective for patients, and even discovered a way to make the transplant more effective.

It turned out that giving patients another type of blood cell called granulocytes soon after the cord blood transplant triggered the donated stem cells to make many more T-cells, a type of immune cell. This is important because more T-cells means more cells fighting leukaemia.

Rob and his team set up a clinical trial to learn more about this treatment, with the hope of offering it to more patients. However, the researchers weren’t sure why the granulocytes made transplants more effective, and why the new donated T-cells didn’t attack the patient’s own cells as well as the leukaemia (this is called graft vs host disease).

The Little Princess Trust funded a project that runs alongside Rob’s trial to find out exactly how the science behind the treatment worked. Rob’s research team is looking at the specific types of immune cells being boosted, and why. He believes that the reason why T-cells increase after a child is given the granulocytes is because the T-cells are trying to attack the granulocytes as if they were an infection.

Rob’s project finishes this year, and he hopes to understand exactly how the granulocytes help, why they don’t make T-cells attack a patient’s healthy cells, and whether they can recreate and improve this effect in the lab.

Rob said:

Although transplant has been used for over 50 years to cure blood cancers, actually very little is understood about what the donor T-cells attack, and how they do not cause graft versus host disease. This is a programme of research to try and better understand this graft versus leukaemia, and whether we can use it in other cancers as well.

Studying the genetics of leukaemia to find new treatments with Dr Stefan Meyer

In 2017, Stefan started work on a leukaemia research project that he hoped would lead to a safer and more effective treatment for children with leukaemia.

His project was funded by the Toti Worboys Fund, a CCLG Special Named Fund set up in memory of Thomas ‘Toti’ Worboys. Toti passed away in July 2014, less than a day after being diagnosed with leukaemia. Since then, his family have been tirelessly raising funds to support research like Stefan’s.

Dr Stefan Meyer and team with the Worboys family when they visited his lab in 2018.

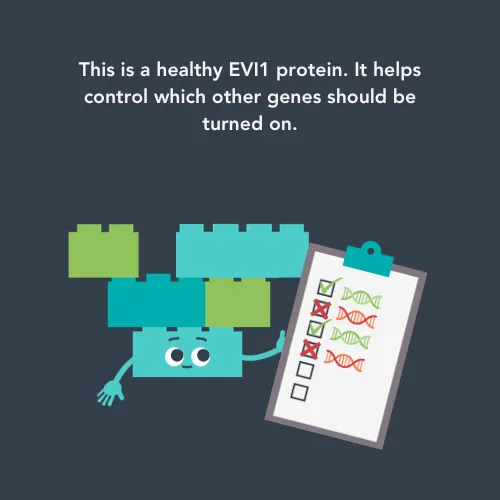

Stefan was investigating a protein called EVI1, which some cancer cells can have too much of. This is important, because EVI1 controls what else goes on in blood cells such as what other genes are turned on or off.

EVI1 is present in some healthy cells too, where it can help maintain the balance between different types of blood cells and ensure that these cells develop properly. Different types of cells need different genes active, so the EVI1 protein can turn a lot of different genes on and off. Whilst this is all important in healthy cells, this amount of power can be dangerous when things go wrong.

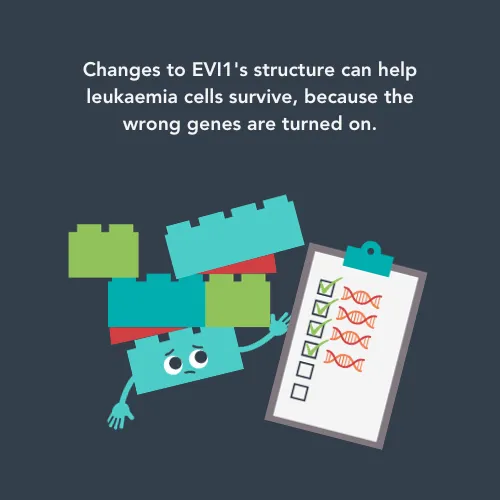

When there are too many EVI1 proteins, such as in leukaemia cells, it can lead to big changes in the way the cancer cell behaves because it impacts so many other processes. For example, the protein can give leukaemia cells advantages that help them resist treatment and grow more. Whilst EVI1 is a well-known issue in a type of cancer called myeloid leukaemia, Stefan wanted to see whether too many EVI1 proteins were also causing problems for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, and what made them cause these problems.

The way proteins behave is partly based on tiny changes to their structure, so Stefan wanted to investigate what changes EVI1 proteins had. His team looked at EVI1 proteins found in patient cancer samples, and conducted tests to find out exactly where on the protein the changes were and what effect they had.

The team found two places that had changes on the EVI1 proteins which affected leukaemia cell survival.

One of the changes meant that some leukaemia cells were even better at copying themselves, which could make the child’s leukaemia worse. Another change stopped EVI1 from keeping the cancer cell in check and made it worse at regulating the cell when a patient was having chemotherapy. This change allows the cancer cell to grow out of control and means that, during chemotherapy, the cancer cell has even fewer limits imposed on it.

Stefan’s CCLG-funded project ended in September 2020, and he is still working on a way to attack leukaemia cells through the EVI1 protein. He published a paper last year on how EVI1 interacts with other proteins, suggesting that changes to EVI1’s structure or the proteins it interacts with could be targeted by new treatments. Attacking leukaemia in this way would mean that EVI1 is no longer able to help the leukaemia cells survive, whilst being potentially safer for healthy cells.

Toti Worboys’ dad Nick wrote an article for Contact magazine about meeting Stefan, where he said:

The most impressive aspect for me is the quality of the brilliant people working at the cutting edge of medical science to crack cancer. The war is being won, slowly but surely. This creates great hope for the future.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG