You’d be forgiven for thinking that researchers and scientists must have always been academic and loved school. But that’s not always the case - there are lots of ways that people start their science career!

Last week I caught up with Dr Jessica Taylor, who started working in science years after leaving school, to see how she got into childhood cancer research, why she made such a big career change, and what she’s working on now. Here’s what she said…

Could you tell me a little bit about yourself?

My name is Jessica Taylor. I'm a postdoc at CRUK Cambridge Institute, and I work in the Gilbertson Lab, which predominantly focuses on paediatric brain tumours as well as the development of cancer in embryogenesis and why we get cancer.

Dr Jessica Taylor

I work mostly on a subtype of medulloblastoma called WNT which is highly curative and very rare. My biggest question is how we can improve the quality of life that these patients have after having had cancer. I'm working on designing new therapeutics and also repurposing existing ones that could make kinder treatments for these children, so that they don't have to live with the consequences of cancer treatment. I also work on a project that could help children get diagnosed sooner, so they can have less aggressive treatment.

Were you always interested in science and cancer research?

Not at all. I probably stopped caring about school when I was about 15, so I only did a couple of months of my AS levels before I dropped out.

I started working in hospitality when I was about 12 or 13, and absolutely loved it. I didn't want to do anything else. By the time I was 21, I was working in quite a large pub and running the functions, running the back room, and just doing everything but science really.

When I told my chemistry teacher that I was doing my PhD years later, I think I gave her a heart attack! The only reason I took triple science was because I really liked this guy, and I didn't have any other classes with him. Mrs Phillips, my chemistry teacher, I think she knew it!

What made you change career?

In 2008, we weren't making much money in the pub. I was in my mid-twenties and everyone else was finishing university. I'd never even been and I would get asked all the time – ‘Oh, so what are you studying? Why are you here?’ It started to get to me a little bit, and I felt like I didn't really know what I was doing. Could I imagine myself here in 20 years, still stood behind a bar?

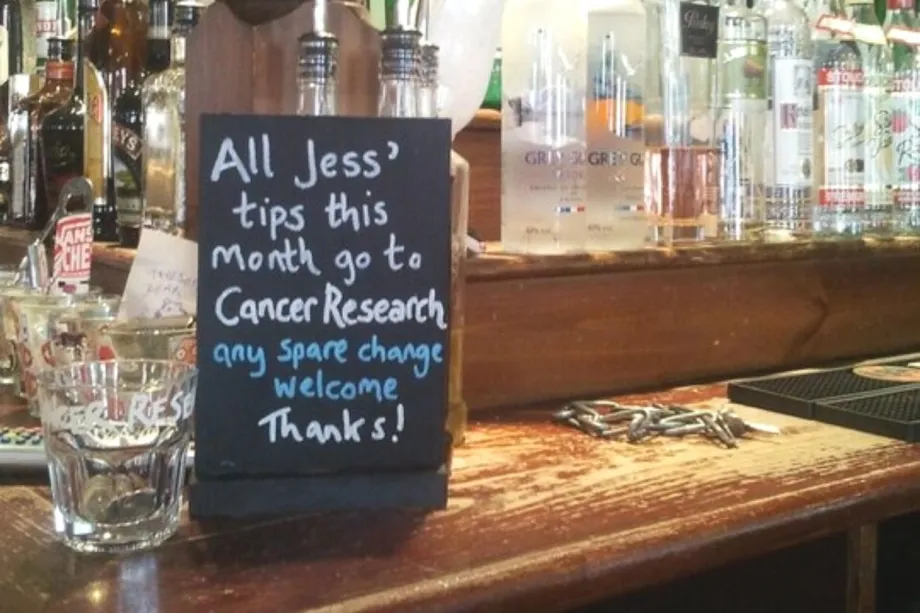

Jessica donated her tips to cancer research whilst working at the bar.

I realised that I wanted to see what else there was out there, did some research and thought I could be an environmental health officer, because that would use my knowledge of running a bar.

I did need a degree, but I found Salford University and they were completely okay with me not having any A-levels. I could do a foundation year with biology, chemistry, maths and statistics instead.

I hadn't written anything with a pen apart from ‘1 x burger’ for six years, so I really didn’t know how I was going to do it. But it was great - I absolutely loved the chemistry lectures and I even got accused of cheating in math because I got everything right.

All of the lecturers were so inspiring, and I realised I didn’t actually want to be an environmental health officer and I’d rather find out more about biochemistry.

That sounds so interesting! How did that lead to working in cancer research?

We did an industrial year, where you go and work in a lab for a year, and I went to AstraZeneca. It was an exciting time to be there, and I absolutely loved it.

They were moving forward with one of the fastest drugs to go through every step of the drug discovery ever. You could see this ovarian cancer drug going from initial biochemical assays to being used for a patient already and then see their CT scan - you could tell it was working. Even though I wasn't in the oncology department, being in that environment was really inspiring.

Around the same time, my family were struggling with having the BRCA1 gene. My auntie was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and my nana with her third primary cancer. She has been sick since 1986, the year before I was born, and she’s struggled a lot with the side effects of her treatment. The radiotherapy burnt so much of her tissue that she had to have her voice box removed and I have never heard her voice.

Jessica's dad and grandma.

She's still alive now but she's had four primary cancers. She's been very poorly for a long time, but it's all the side effects of the treatment rather than the cancer itself. So, when I finished my degree, I wanted to do a PhD in cancer.

That sounds difficult for you and your family. I imagine it provided a lot of the motivation you needed to go through university as a mature student. How easy was it for you to become a researcher so many years after leaving school?

I think it was tricky in some ways, but I don't think it was because of coming back. It was more not knowing what I was doing, just from my background more than anything, and not having the right people to talk to, or not wanting to ask questions and risk sounding stupid.

At the time, I didn't know anyone who'd done a PhD or why, I didn't know the route and what was supposed to happen. It was tricky in that sense, to not have that background.

AstraZeneca showed me that you don't need a PhD necessarily to be a scientist. That industrial year gave me a lot more knowledge about what I was doing and what paths there were. But it also told me that I didn't want to work in industry because I didn’t want to be a little cog in a big machine. I wanted to focus on what I found exciting, which is why I did end up doing a PhD.

What is the best thing about working in childhood cancer research?

I think the best thing for me is that everyone is so motivated. When you hear how people talk about their research and the impact it's going to have, it's a huge difference.

Childhood cancer is also really fascinating because it's so different from adult cancer. Childhood cancer can be caused from just one little thing happening, which then cascades. Knowing how close the difference is between normality and a potentially devastating disease is really frightening, but it's so interesting. I want to know why that happens and how we could potentially stop it from happening or reverse it.

What are you working on at the minute?

At the moment, we're looking at making diagnostic probes for medulloblastoma through a project with The Brain Tumour Charity.

There are four main subtypes of medulloblastoma, and all of them have very different proteins on the surface of the tumour cells. I'm looking at which proteins are highly expressed on the cells of each subtype, so we can make multiple probes that binds to those proteins and are visible on PET scans. This could diagnose the subtype of medulloblastoma based on which probes you can see attached on the scans. This could help before major surgery, or so doctors can keep watching the tumour as it's going through treatment to make sure it is successful.

In the WNT subtype of medulloblastoma, there's no correlation between gross resection, where they take as much as possible of the tumour, and survival - it's the chemotherapy and the radiotherapy that are curing the tumour.

If we can diagnose which type of tumour it is before surgery, then we could tell the surgeon to only take what's damaging the brain’s structure and causing the inflammation. Then hopefully that'll avoid long term damage for patients.

That sounds useful – and a very different way of improving treatment to your project funded through us! In your Little Princess Trust project, you are using antihistamines which are already used worldwide for allergies. Why is this important?

If you have a new drug, it can take up to 15 years for it to reach patients, and it's very expensive to make sure it is safe. So, when you want to be helping the children who are sick now, it's a lot more beneficial to use existing medicines.

In my project, I’m seeing whether antihistamines can kill medulloblastoma cells by overloading lysosomes. Lysosomes essentially do all the recycling in a cell, like getting rid of the bits that the cell doesn't need. But if the lysosome bursts, the cell has to kill itself. A group in Denmark showed that cancer cells have a more fragile lysosomal membrane in cancer cells. This means you can more easily burst lysosomes in cancer cells.

There's a whole huge class of drugs that will do this, including loratadine that you take for allergies. When I did the initial pilot experiments back in 2018, we showed a very small, but reasonable, increase in survival in an adult glioblastoma cancer model with loratadine. I wanted to try the same idea for childhood cancer, and I was initially doing a lot of these experiments with Prozac as well as loratadine.

From a parent’s perspective with a young child, being told that they've got a brain tumour and then that we also want to put them on Prozac – it felt like a lot. Whereas, if I can get it to work with the loratadine, and it's a common medicine that feels safer.

So far, we have seen another increase in survival when loratadine is given to mice with medulloblastoma. However, we’re not sure if the loratadine is killing the cancer cells or whether it’s making the mice hungry, which makes them tolerate treatment better.

I've done all the pharmacokinetics of the drug and we can see that there is loratadine in the brain tumour - it's definitely getting through. But loratadine shouldn't get into your brain normally. It’s really interesting, but it's not actively causing cell death in the tumour from what I can tell.

What’s next for this work?

In Denmark, all medicines needed to be prescribed until recently, which means there’s a lot of data they can use to assess which medicines might help with different diseases. They did this huge study and found that the only medicine people took that correlated with breast cancer survival were antihistamines that people were taking for their allergies. So, we know it works for some types of cancer.

I’m thinking that maybe the loratadine is doing something with the immune system, seeing as the antihistamine helps fight tumours where there are immune cells, like breast cancer, but doesn’t for those which don’t have active immune cells, like medulloblastoma. I'm trying to now see if we can stimulate the immune system somehow to make loratadine work better. I just really want to find out exactly what is happening and why!

One thing I’ve noticed with researchers I talk to is that they’re always so driven and curious – which you definitely are! Do you ever miss your old job in hospitality?

I did miss it a lot when I moved to Cambridge - I was looking for shift work in a bar just to make friends. Then I met my partner instead! He is a brewer and we have two bars and a brewery now. So, I get to have all the fun of hospitality work with none of the closing up at two in the morning!

Sounds perfect! So, for our last question - is it ever too late to become a researcher?

I think it's never too late to see if it's for you. Age or background shouldn’t stop you from trying it. Research is very demanding in terms of time though and, if you really want to go for it and do well, it's a lot of commitment. If you really love it though, it doesn't feel like commitment.

I think the best way to see if you do love it is to do things like an internship or a placement. There are loads of different things you can do and people are always happy to show you around.

People will let you do that if you ask - I never really understood that until I came to Cambridge. You can just email people and say, can I come and work with you for the week? It was always ingrained in me that in that world you can't just like push your way in like that.

Jessica and her grandma at her PhD graduation in Manchester.

I never even thought of doing that when I was a student - I would have been terrified of emailing a researcher!

We get emails asking, can I come and do a project in your lab? Can I come here? I've got some funding - can I come and do this? Or can I just come and see what your lab's like? And if you ask enough people, someone will say yes.

My best tip is don't email principal investigators, the boss of the lab, because they don't read our emails, never mind anyone else's email! But a lot of postdocs and PhD students are really keen on sharing their research with schools or people who want to get into science.

I think if people are interested in children's cancer research, there're so many great labs in the UK. So just contact us!

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG