September is Childhood Cancer Awareness Month and this year our theme is ‘Research’. We want to raise awareness of the importance of childhood cancer research, and how it can improve the future for children with cancer.

Last week, I spoke to Scott Crowther to find out what it’s like getting involved in research as a parent. Scott and his wife Sarah’s youngest son Ben died in June 2019 only a year after being diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma. Scott now volunteers as a member of the CCLG Patient and Public Involvement Group and spends his time advising on research projects as a patient advocate.

Scott with his wife Sarah and three sons (left to right: Sarah, Ben, James, Scott, and Harry)

Why did you want to get involved in childhood cancer research?

When Ben was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma, a cancer we had never heard of and couldn't even pronounce, we did a load of Google research and contacted other parents whose child had been diagnosed with the same cancer.

We found that the chemotherapy drugs Ben was treated with were first developed over 40 years ago. It was hugely frustrating and upsetting that there were no better options for our son.

So, when Ben died a year later, Sarah and I were already doing quite a bit of fundraising through friends, family and our community. We had to decide what to do with that money.

Ben Crowther

It’s a no-brainer that we need more research to understand the disease so that we can develop new treatments for it. We wanted to do what we could. Some of that is by fundraising for research through our Special Named Fund called ‘Pass The Smile For Ben’, but I also realised I might be able to help somehow with the research projects themselves.

How did you start getting involved?

I went to a CCLG conference in London with Sarah after Ben died. We met Ashley, CCLG’s CEO, and he introduced me to Susie Aldiss. She was working on what has become the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership, setting the top ten research questions for childhood cancer. They invited me to be a parent advocate on that research project.

When I walked into the first meeting, it was a big team. One of them was an oncologist who treated Ben and had 40 years of experience in the medical world.

The Priority Setting Partnership team, with the final top 10 childhood cancer research priorities

I sat there thinking ‘Why am I here? How am I possibly going to give anything of value to a room full of professionals with 200 years of collective medical experience, and people from charities who fund research?’ But, within about 15 minutes of my introduction, people were asking me questions and for my opinion.

I realised that I had the one thing they didn't have, which was lived experience. They don't understand that, despite in some cases treating families themselves. They've still not walked in our shoes. They don't quite understand what it's like.

Did you have any experience with this before?

I had no experience at all to start with, but I think I've worked on eight projects now!

My day job is at the University of Warwick, where I build collaborative research projects and apply for funding. It was that experience and skills that I thought might be useful within the medical research world.

It must help to have those transferable skills and a basis to start from.

I think so. I met a Canadian advocate who says that, if you look at the parents who are representatives on these projects, we're all intelligent skilled people with expertise in our fields. It just happens to not usually be medical or lab-based. We may have had a terrible journey, but we can relay that into the project in intelligent ways - we're not just token representatives.

How do people with lived experience contribute to research?

There are three things that I think are key. Number one is to give our children a voice within the project so that scientists understand the needs of the children, and why the work they're doing is important.

Visiting scientists in Portland (USA) to share Ben’s story

The second is to help with the information given to families for clinical trials. Families get given a lot of information when their child starts a trial, and it needs to be clear. We help draft that and even suggest videos or translations into other languages – things that wouldn't necessarily occur to the scientists.

I'm also particularly passionate about explaining science to the public. I don’t want people to just hear there's a scientist in a lab somewhere who spent 10 years developing something and look at this great new medicine they've developed. I want to explain all the amazing research I've learned about.

What else do you do to influence and advocate in research?

I started to talk to scientists who don't work in rhabdomyosarcoma, saying that I think they should consider it as there are not enough scientists researching this type of cancer today. There is funding available, but there aren't enough scientists in the field to apply for it.

I'm pleased to say that my conversations with scientists have been successful! One of the new CCLG-funded projects is with a researcher called Dr Darrell Green who's doing a rhabdomyosarcoma project for the first time, having previously worked on bone sarcoma.

I saw a press release about the work Darrell had done to get a new bone sarcoma drug into trial, and I thought it was fantastic.

I approached him as a parent and said, ‘I think this is an underserved area, why not consider doing it?’ He agreed, and he's now got a funded project.

You're now working on international projects and attending scientific conferences - what's that like as a parent?

At the conferences, you're in a room with scientists for multiple days. You get quality time with them, and there's the opportunity to ask for a lot more detail. I've learned a lot about cancer research science from conferences, and about what researchers want to know that makes a difference to them.

The most impactful thing to tell them about is our kids. I've told them about Ben and other kids we know too, and about their experiences while they're on treatment. Like trying to swallow tablets or lack of sleep or having horrible nasal gastro tubes fitted. A lot of the scientists don't see this because they work in a lab doing experiments rather than with patients.

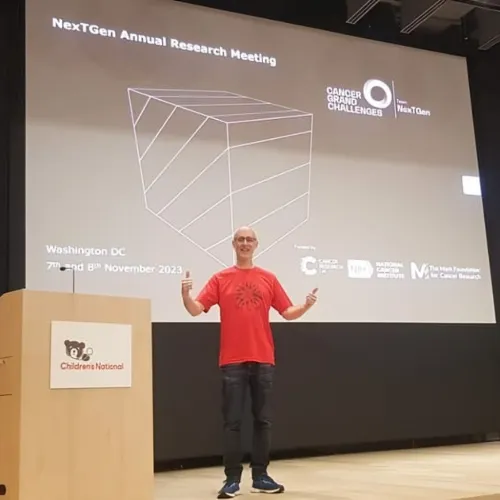

Sharing the importance of parent and patient involvement at an international meeting.

Hopefully, this all leaves an impact on the people that we meet, and they will carry on realising how important their work is.

Have you faced any challenges while advocating for cancer research, and how have you overcome them?

One challenge is the emotional side of talking about my son, Ben. I'm happy to do it, despite it upsetting me. One of the hardest things is looking around the room and seeing that half the people in the room are also in tears. I do usually say at the end that I didn't come here to upset anybody, but this is the reality of our lives.

The second thing is that I've developed some anxieties since the experiences we went through. The idea of standing up in front of a room of people is hugely anxiety-inducing now, whereas I wouldn't have had that problem before. When you combine talking about my son together with standing up in front of 60 people, that's quite a hard concoction to confront.

I don't want anybody else reading this to think that they have to go and stand up in front of people though. They don't - as a patient advocate, there is never any pressure for you to do that. They can just go to a meeting, give their opinion, and that's it.

I decided it's good for me and I feel somebody has to do it. This sort of thing is fulfilling because it helps us keep Ben's name alive. It helps us to know we're doing something positive to help and gives us a purpose.

Are there any moments where you felt like your contributions made a difference for the project?

A lot of it is little touch points rather than moments where you can say ‘I influenced that specific thing’. There'll usually be a small group of patient representatives too, and so it's collective thinking. We all put ideas in, and work on them as a team.

The NexTGen project’s patient advocate team.

However, after a presentation in San Francisco recently, I had loads of emails from the people at the company thanking me for telling the story and helping them understand why what they're doing is important. The company hadn’t worked on children’s drugs before, so it was a whole new area for them. I was the first patient advocate for childhood cancer that they met. They were very driven anyway, but they feel even more driven now.

What advice would you give to researchers on effectively collaborating with parents and families?

Get a family and at least one representative involved with your lab now, before you even develop the idea for a project. I think researchers are missing opportunities to get family input at the birth of an idea.

It would mean that their project will ultimately be relevant to families. For example, if you were going to invent a new drug to treat rhabdomyosarcoma, but you told me that the tablets were large I'd say there's no point. You're never going to get a five-year-old child to take a tablet of that size. That seems like a really small thing, but it's really important. You'd be surprised how that sort of thing isn't thought about by the scientists at the beginning.

Would you recommend PPI work to other people with experience of childhood cancer?

Without a doubt. It isn't for everybody, but we need more family representatives. For one thing, more women do this sort of volunteering work than men - other men are doing it, but not that many. Also, I would say 98% of the PPI people I've met are white. That means we've got poor representation of ethnicity across all the projects. We need more people from different backgrounds to get involved.

You can contact a research project that's got a patient representative or advocate on it and speak to them if you want to find out more about it. Or you can contact me through CCLG. There’s also the CCLG Patient and Public Involvement Group, which advises on new CCLG research projects.

I appreciate it's not for everybody. There can be difficult conversations and things to learn about. It can be quite emotional. But I think the ability to give back and the hope that you are helping create a new treatment outweighs any of the difficult stuff.

It's still difficult, but it's worth it. My hope is that while I'm still here on this planet, we will find another treatment for rhabdomyosarcoma to really help children. I don't know if it'll be from my projects, but I'm optimistic that something will happen.

Scott camping with Ben.

You can support research into rhabdomyosarcoma by donating to Pass The Smile For Ben, the CCLG Special Named Fund set up by Scott and Sarah.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG