Proton beam therapy is a type of radiotherapy that uses high-energy proton beams, rather than high-energy X-rays, to treat some types of cancer, including those in children. The UK now has two specialised proton beam therapy centres for patients with cancer in Manchester and London.

So, how does proton beam therapy work? A large and complex machine shoots protons (tiny parts of the atoms that make up everything around you) directly at the tumour in the body. These protons are targeted very carefully and stop once they hit the tumour, delivering a burst of energy that attacks the tumour. As it is so specifically targeted, it is currently only used on a few types of tumours safely such as brain tumours and sarcomas.

Who can it help?

Researcher Dr Mark Gaze wants to learn more about how proton beam therapy could help children with tumours in their abdomen. Normally, these children are treated with radiotherapy, which can be effective at killing tumours, but can also cause damage to healthy organs nearby. Doctors try to balance killing as much of the cancer as possible with keeping the surrounding healthy tissue safe.

Proton beam therapy is more specific, as the beams stop a certain distance into the body, unlike normal radiotherapy beams which continue indefinitely. Proton beam therapy therefore causes a lot less harm to the healthy tissue beyond the tumour. Although some people believe proton beam therapy is the best option because it has received a lot of publicity and there are potentially fewer long term side effects, Mark said:

In medical treatments, there is rarely an 'always' or a 'never'. The answer most often is 'sometimes'.

Proton beam therapy is mostly used for tumours in areas of the body which do not change shape, like the brain. Abdominal tumours such as neuroblastoma are an example of when proton beam therapy isn’t always a clear-cut decision. The abdomen is a very variable area – it can change a lot due to breathing, gas, or a child’s position, and slight changes can mean that the carefully aimed protons end up hitting healthy tissue or missing parts of the tumour. This can cause damage to healthy tissue or failure to cure the tumour.

Mark works at the University College London Hospital, where one of the proton beam therapy centres is based. He trained as a clinical oncologist, a doctor who specialises in treating cancer with radiotherapy, and he said that whilst “most childhood cancers are curable, survivors may have to live the rest of their lives with long-term consequences of treatment. It seems that research had two aims: to increase the chances of cure, and to make cure possible with fewer late effects.”

Little Princess Trust research

Funded by the Little Princess Trust, this research has been published in multiple peer-reviewed academic journals. Mark’s team, including research fellow Dr Pei Shuen Lim, have worked out how to tell if a patient would benefit from proton beam therapy instead of standard radiotherapy.

Dr Pei Shuen Lim

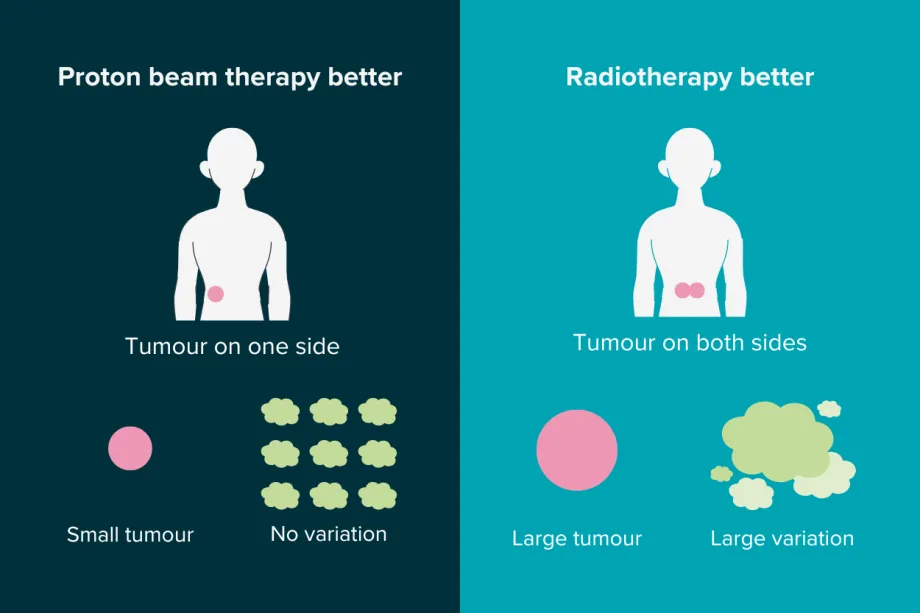

The research suggests that children with smaller tumours that are just on one side of their body could be better treated with proton beam therapy. The team also found that differences in the amount of gas in the abdomen could have a big effect on whether the protons reached the tumour, and so children with large variations in gas were better treated with normal radiotherapy. “The amount of air in a child's tummy can vary significantly from day to day” said Pei, and “this may reduce the proton dose to the tumour, or increase the proton dose to healthy tissues. Conventional radiotherapy is much less affected by air-filled spaces in the body.”

The factors that can help decide which treatment will be most effective.

Now the researchers have established that proton beam therapy could work for some children with neuroblastoma tumours in their abdomen, they have started on the next phase. For proton beam therapy to work best, doctors need better scans of the area to be treated. Mark and his team are working on creating guidance that tells doctors what scans are needed and how to make them safer with lower amounts of radiation. Mark and Pei, with the team, are also trying to set up a clinical study to see if proton beam therapy could help more neuroblastoma patients. He said that the team “hope to set up a study in which children with neuroblastoma requiring radiotherapy come to one of the two proton beam therapy centres in Manchester and London. We will carefully plan treatment with either protons or conventional radiotherapy, and deliver treatment with the type shown to be better. This will be personalised treatment. We want every child to have the best possible treatment.”

Mark and Pei believe that this work will help improve treatment for children with neuroblastoma. Both standard radiotherapy and proton beam therapy will benefit from the work done to improve guidance and, hopefully, in the upcoming clinical trial, children with neuroblastoma will soon be benefiting from this new application of proton beam therapy.

Dr Mark Gaze and Dr Pei Shuen Lim, with Dr Yen-Ch'ing Chang and Dr Jennifer Gains, in one of the proton beam therapy treatment rooms.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG