So far on this blog we’ve covered the ways cancer is different to healthy cells, targeted therapies, and much more. But here’s a new concept: models.

In cancer research, ‘models’ can be naturally existing or artificially created such as single cancer cells, fruit flies with genetic mutations, or other more complicated organisms. The models share features with human cancers, which can help scientists understand more about how the cancer works and to predict which medicines might fight it.

Using cancer cell models

‘Cell lines’ can be grown for many standard types of childhood cancers. They are a type of model consisting of cancer cells grown from tumour biopsies, which let scientists grow lots of cancer cells in the lab more easily. As we learn more about cancer through advances in genetic and molecular analysis, we are finding new subtypes of cancer. To have a better idea of how these subtypes behave and how doctors should treat them, new models such as cell lines are needed.

Professor Karim Malik is working on Wilms tumour, a type of kidney cancer that affects young children. There are many subtypes of Wilms tumour which all look and behave differently – and they each need different treatments. Karim said that “some subtypes display good responses to current treatments but there are still aggressive tumour types that are difficult to treat.”

There are several factors which can affect which subtype a Wilms tumour is. Understanding these factors can help doctors predict how well the cancer will respond to treatment or helps them to select which treatment to use. In other cancers, like neuroblastoma, one of these factors is a protein called MYCN. Having too much of it can make the cancer more likely to spread through the body, and less likely to respond to treatment. Based on research showing that there can be lots of MYCN protein in Wilms tumours, Karim believes that it is causing similar effects in children with Wilms tumours.

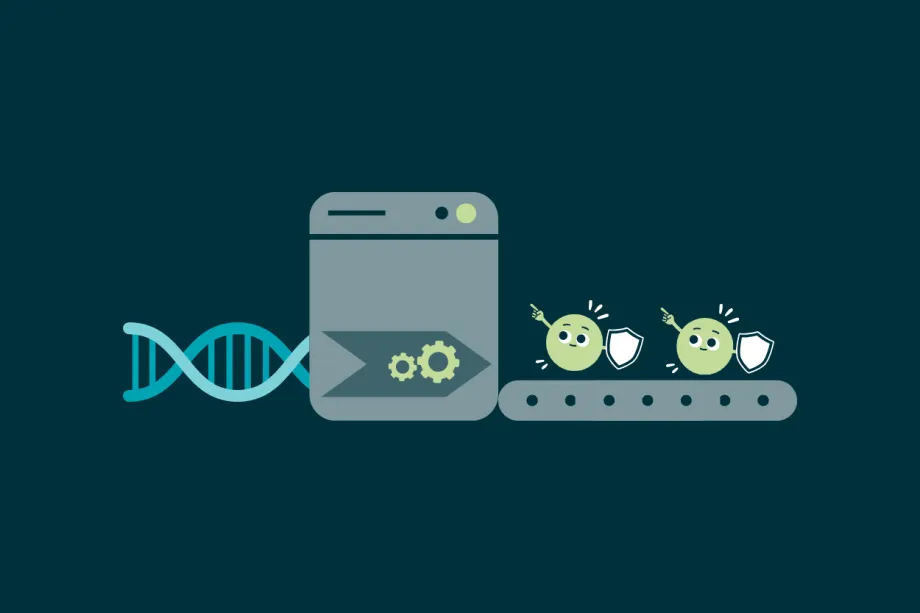

Healthy cells make proteins that can stop tumours from growing.

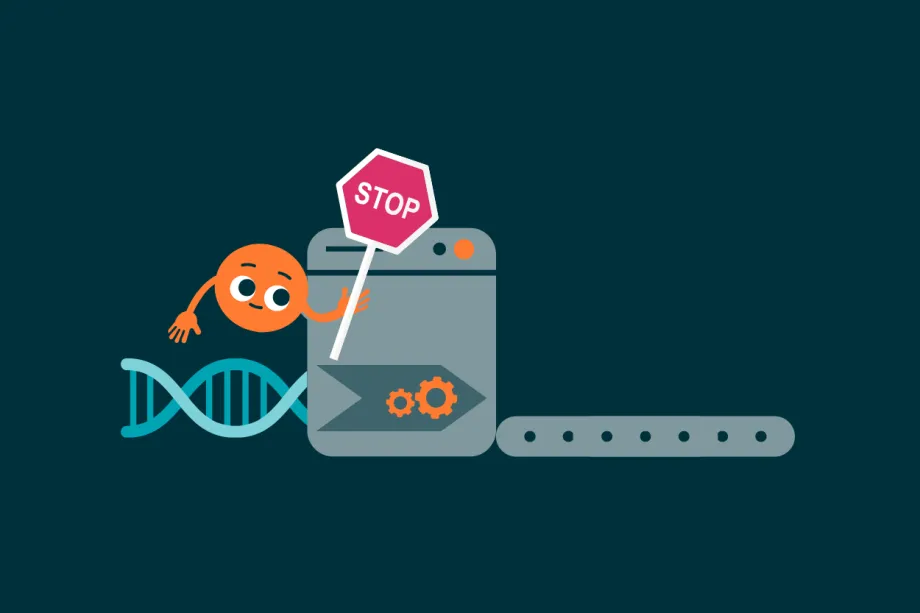

MYCN is an important protein in healthy cells. However, in cancer cells, it can make cells stop producing tumour suppressor proteins, which means a cell more likely to grow out of control and become cancerous.

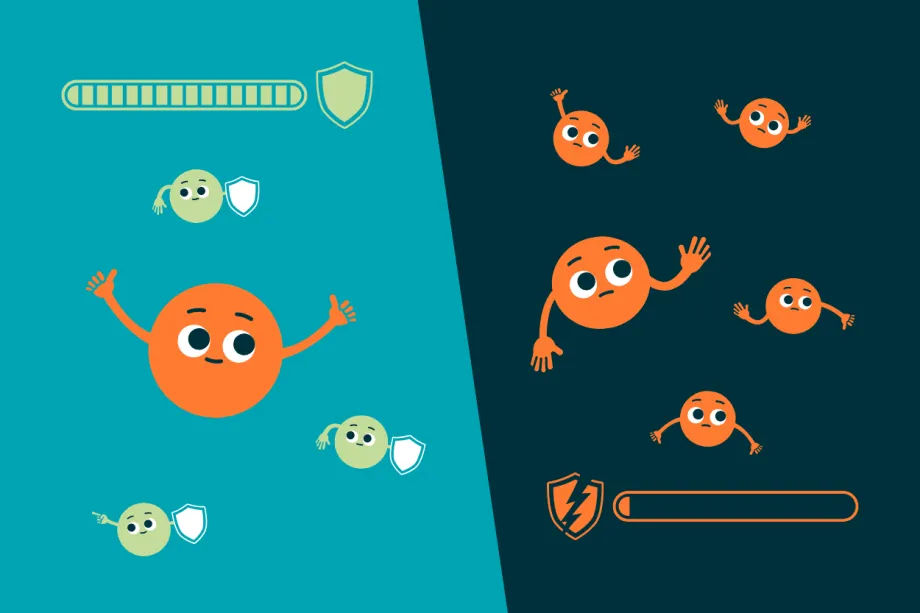

When there aren’t many MYCN proteins, healthy cells produce tumour suppressor proteins. This helps protect the cells from becoming cancerous. In cancer cells, there are too many MYCN proteins. This makes the cancer grow more and be harder to treat.

In MYCN-driven cancer cells, there are far too many MYCN proteins. These stop the production of tumour suppressor proteins, allowing the cancer to grow and spread through the body. Sadly, this makes MYCN-driven cancers even harder to treat.

MYCN in Wilms tumour

To learn more about MYCN’s role in Wilms tumours, Karim’s team at the University of Bristol have created a new cancer cell model from patient tumour samples for MYCN-driven Wilms tumour. They used the model to look at the differences between Wilms cells with normal amounts of MYCN and the model cells which have extra copies of the protein.

The model cells helped show that MYCN plays an important role in how Wilms tumour cells grow. The team found that the protein was present in places where it wouldn’t normally appear, and that it changed which other proteins were also present in the cancer cells. This reduces the number of other proteins that help stop the cell from becoming cancerous. Whilst other research had suggested that MYCN is an important factor to consider in Wilms tumour, this project provided direct evidence that it is vital in understanding and treating some types of Wilms tumour.

To validate their findings, Karim and his team used medicines, which aimed to reduce the amount of MYCN protein present, to investigate how Wilms tumour cells coped when there was less MYCN available. He found that it slowed down the spread of tumour cells, saying:

Although the MYCN gene has been proven to directly cause neuroblastoma, there was no comparable evidence for Wilms tumours. My lab’s molecular biology experiments proved that MYCN is required for Wilms tumours to grow.

"Scientists have made great progress designing new drugs that interfere with MYCN, and so our work will open new therapeutic options for patients with poor prognosis Wilms' tumour. We hope that our study will be able to impact patients in 5-10 years."

What’s next for Karim’s team?

The researchers still have lots of work to do. From their tests, the team found a potential treatment MYCN-driven Wilms tumour which went on to form a Little Princess Trust funded research project. They also want to create new, more complex, genetically engineered models for MYCN-driven Wilms tumours to help future research.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG