You might know that cancer is caused by something going wrong in the cell’s genetic code, the set of instructions every cell has that tells it how to behave and what makes you unique. But it’s not always clear where these errors come from.

We get our genetic code from our parents. Half of our genes come from our mother, and half from our father – which is why children don’t look like identical copies of their parents. It therefore makes sense to assume that any genetic errors that result in childhood cancer have been inherited from our parents – but this is rarely the case.

In adults, a mix of factors like pollution, UV rays from the sun, alcohol, and smoking are leading causes of cancer.

Most adult cancers are due to natural aging, environmental and lifestyle factors. For example, smoking too much and being exposed to UV rays from the sun can damage your cells’ DNA, causing cancer mutations. However, these changes can’t usually be passed on to children.

In children, it is rare to have a cancer caused by environmental factors because they have not been exposed to these factors for as long as adults have. However, there are lots of other reasons why a child will still develop a genetic error that leads to cancer. These errors can also happen at any age – from congenital errors that happen in the womb all the way through to adulthood. Now, all children with cancer are offered whole genome sequencing, to find out which errors they have.

But where do these errors come from?

Genetic errors

All of the types of error mentioned in this blog come under ‘genetic errors’, as they are all related to damaged DNA. So, I’m going to save this section for just those errors that happen on their own. These are something that scientists call ‘acquired mutations’.

DNA is made up of different combinations of four tiny proteins, called nucleotides. In total, our DNA is over 3.2 billion nucleotides long.

Every day, cells make copies of themselves to replace old cells or to support growth. Because every cell has to contain the full genetic code, which is over 3.2 billion units long, DNA is constantly being copied. If you imagine how many errors you might make if you typed up a 3.2 billion letter document, you can start to see how spontaneous genetic errors happen. Scientists believe that there are around 120,000 mistakes made every time a cell copies itself. Cells do have their own form of ‘spell check’ which can fix 99% of these errors, and there is a review process which mops up that last 1%.

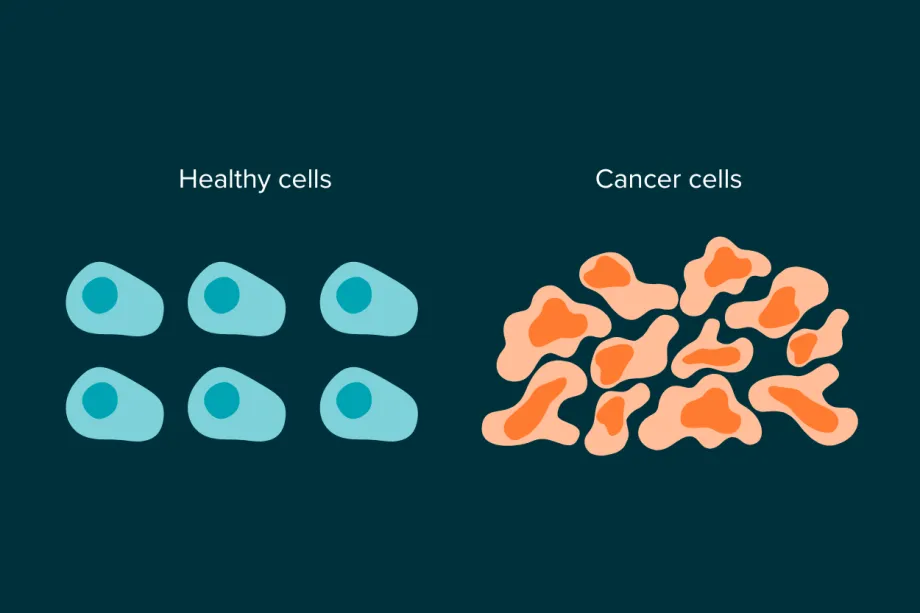

As most people don’t have cancer, this process is quite effective. Sometimes though, errors aren’t caught. These errors don’t always have a big effect on how a cell works, or lead to cancer. However, some mutations are in genes that are really important in keeping a cell healthy. It normally takes about six of these errors for a cell to become cancerous. However, each time a cell with an error copies itself, it has the chance to acquire more errors. When the errors accumulate in part of the genetic code that controls an important function, like replication, it can cause havoc inside the cell.

These changes are what lead to a cancer cell growing and replicating out of control.

Cancer cells ignore the rules that say how many times they can copy themselves, replicating over and over again.

Congenital

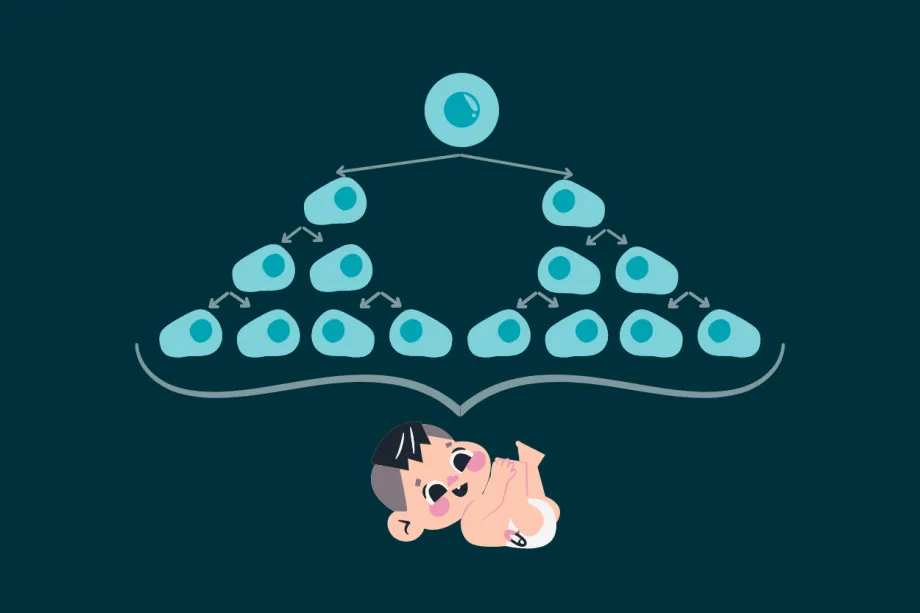

Congenital genetic errors are new errors in a baby’s DNA that happen whilst it is developing in the womb – they can happen anytime from an embryo to when a baby is born (although they are more likely early on). These errors haven’t been passed on by their parents. Most of these are acquired mutations – after all, growing from just two cells of the sperm and egg to around 26 million cells that make up a baby takes a lot of copying. And, as we know, copying is where the errors occur.

To get from a fertilised egg cell to a baby, every single cell needs to copy itself around 41 times - making millions of cells.

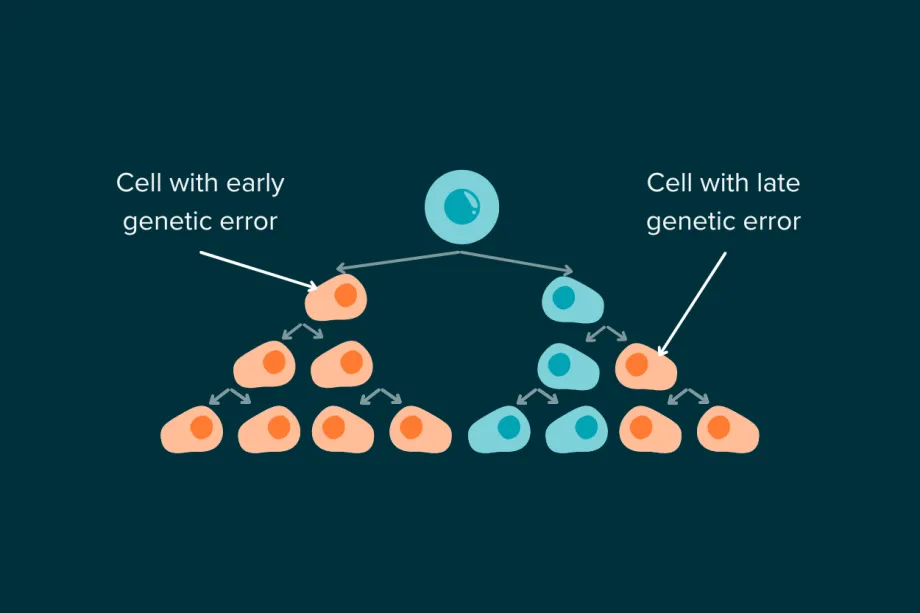

Errors that happen earlier on, in embryos or foetuses, can affect more cells. This is because cells in the early stages of pregnancy have a lot more copying to do to become organs and tissue.

If an error happens early on, all of its copies will also carry the error. If the error happens later, it will affect fewer cells.

Scientists believe there may be a relationship between environmental factors and some cancers, but it is very hard to conclusively say whether a mother being exposed to certain factors always makes childhood cancer more likely. It’s important to remember that exposure to many of these factors, like traffic pollution, are mostly out of the mother’s control and difficult to even know if they are present.

Hereditary

Researchers estimate that only around 5-10% of childhood cancer is caused, or partially caused, by genetic errors inherited from a parent.

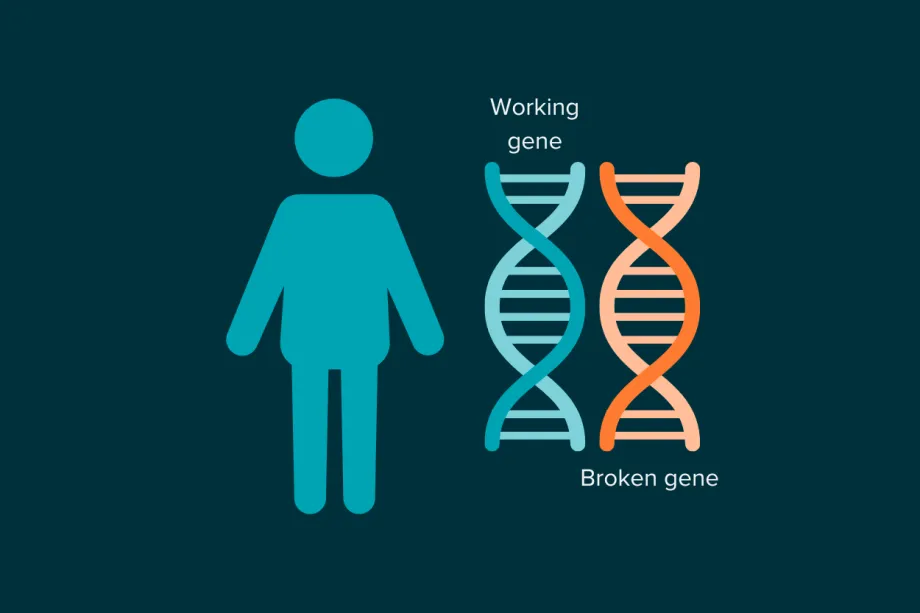

Everyone inherits two copies of every gene. One comes from their mother and another from their father.

These errors can sometimes be called a ‘cancer predisposition syndrome’ or ‘family cancer syndrome’. You can find out a bit more about these in this article.

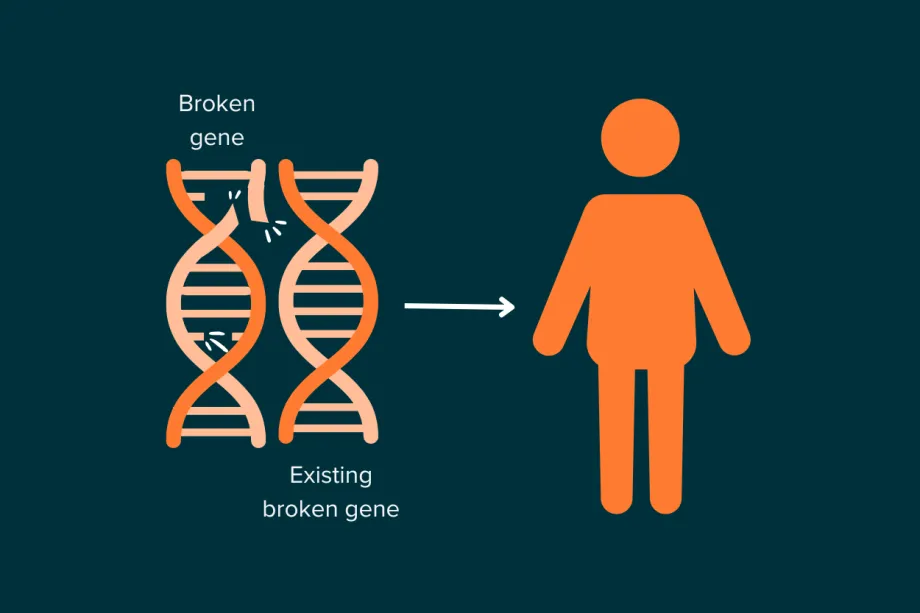

The parent might have always had the genetic error and not even know about it. Everyone inherits two copies of each gene – one from each parent. For some syndromes, as long as one copy was error-free, the parent may have had no signs of being predisposed to cancer. Or the error could be an acquired mutation in an egg or sperm cell, and so would have no chance of affecting the parent.

Sometimes, if there is one working copy of a gene, it won't be obvious that the other copy is broken.

If the other copy of the gene breaks, the person will develop cancer. Because they only had one working copy of the gene, they were always one step closer to getting cancer.

As for adults who do not have inherited genetic errors, but have acquired mutations over the years that have caused cancer, these acquired mutations are rarely able to be passed on to children. Only the DNA that is contained in egg or sperm cells forms part of a child’s genetic code. Therefore, genetic mutations in cancer cells and elsewhere in the body of the parent won’t affect their child.

The two-hit hypothesis

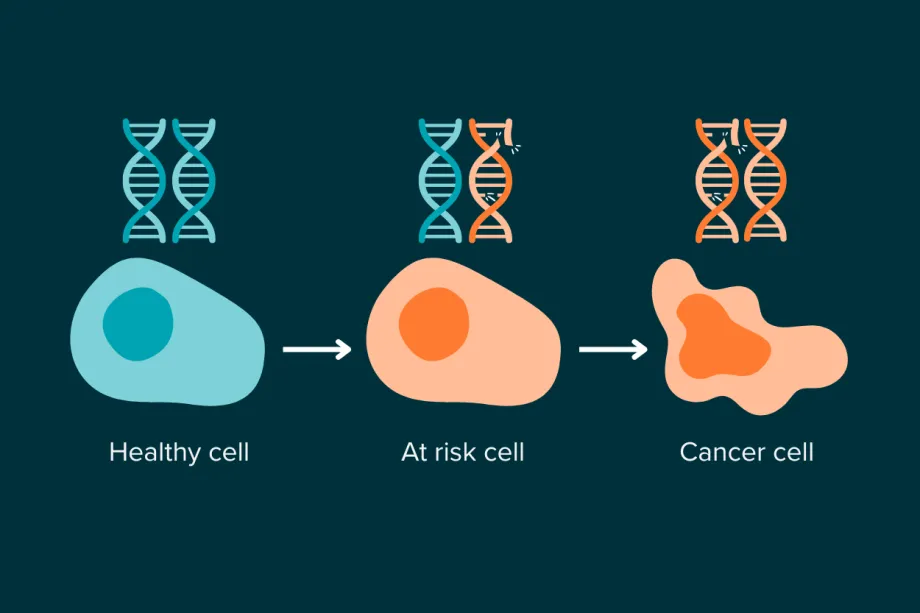

Even if a child is more at risk of developing cancer, or has a relevant genetic error, it doesn’t mean that they will develop cancer. Although there are normally a number of mutations needed to cause cancer, experts think some cancer types, such as retinoblastoma, need two ‘hits’.

A healthy cell becomes at risk after the first 'hit' - a genetic error. The at risk cell is not cancerous, but can develop cancer if there is a second 'hit', like another genetic error.

The first hit is the genetic error – whether inherited or an acquired mutation. At this point, the child does not have cancer – they are just more at risk of it. If there is a second hit later in life, such as an infection or further mutation, this is when they will develop cancer.

There’s still a lot of work being done on this, to find out what form these hits take, and which cancer types it applies to. Dr Mel Greaves, from the ‘Can we prevent childhood leukaemia?’ blog post, has done a lot of work in this area.

So, there you have it! I hope that this has helped you to understand the differences between these groups, and why not everything that is ‘genetic’ comes from your parents.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG