The phrase ‘survival of the fittest’ is often incorrectly attributed to Charles Darwin, who is known for transforming the way we understand evolution. Darwin actually called his idea ‘natural selection’ and refused requests to use ‘survival of the fittest’ to explain his concept. However, the phrase has stuck around because it captures the essence of the fight for survival experienced by all living organisms.

According to the theory of natural selection, there is variation between different individuals in a species and sometimes these variations or traits can be passed on to offspring. If one of these heritable traits made the animal better at surviving and reproducing, the animal would be more successful and therefore be more likely to pass that trait on to their offspring.

For example, there is a type of moth called the peppered moth. It is white with little black speckles, which help it camouflage itself against trees to avoid predators, but a few of these moths are naturally black. During the industrial revolution in the 1800s, there was so much pollution in the air that tree trunks turned black from soot. This made it really easy for birds to see the white moths, and few of them survived. The black moths did great as they were almost invisible to birds, and so happily survived and passed on their dark colour genes.

Can you see all four moths? Camouflage only works if you’re in the right environment. You can easily see the light moth on the dark background and vice versa. You can see why a dark moth would be more likely to survive and reproduce in a dark environment.

This is a great example of natural selection in action, where a trait affected which individuals survived and was then passed on to offspring, giving those offspring an advantage. Eventually, little changes like this can accumulate to completely change a species or create a new one.

Darwin’s work was all based on individual organisms competing with each other – but what if there’s also competition within organisms?

Could cells be competing?

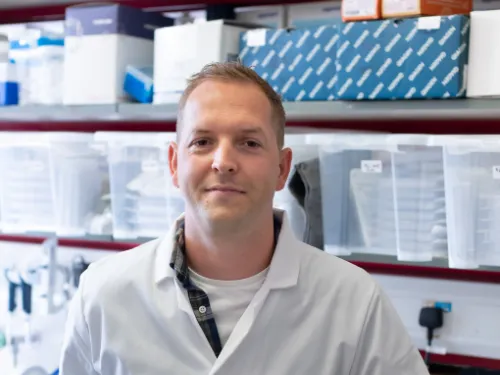

Natural selection has historically been about individuals who are fighting against each other, for survival or for mates. Until recently, researchers believed that cells in the body didn’t compete because they were all working towards the same goal of keeping you alive, and therefore couldn’t be evolving. But that’s not the case.

It turns out that cells can be brutal – from causing their competitors to commit suicide to cannibalising them for parts. It’s not the ordered society with strict rules that researchers believed. Cells can sense whether their neighbours are ‘fit’ or not and will push out or fight any ‘unfit’ competitors. It’s a little like if one of the runners on the Olympic relay running team was too slow – they would very quickly be removed from the team and replaced with a faster runner.

In a relay race, running slowly doesn’t only put you at the losing end of the race, it also puts your whole team at risk of losing. For the good of the team, the slow runner needs to be replaced with a fitter competitor.

Most organisms made up of many cells have this cell competition, suggesting that it must be an advantage that we have evolved to maintain. Researchers believe that cell competition can act as a sort-of quality control system, making sure that the very best cells are used in each tissue type. Cells keep a constant watch out for other cells that are sick or not doing their jobs properly. These are then dealt with - usually forced to die to make way for a cell that is fit.

What about cancer?

So, how does all that apply to cancer cells? There are a few answers to that, partly because there are a lot of ways in which cells can sense the fitness of their neighbours. This means it can be difficult to predict how healthy cells would react to different types of cancer cells.

Cancer starts out as a healthy cell, which is slowly transformed into a cancer cell by genetic errors. This means that cancer cells are genetically different to their neighbouring cells and gives the potential for competition with healthy cells.

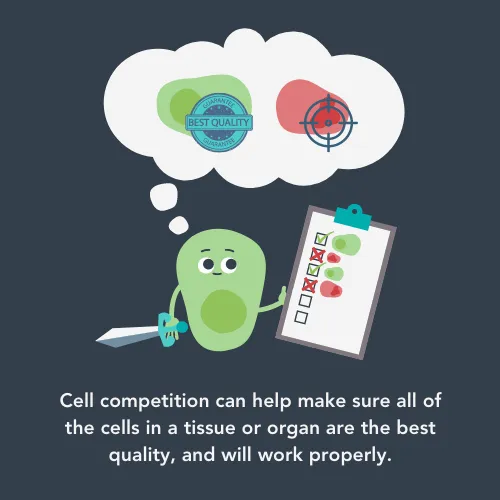

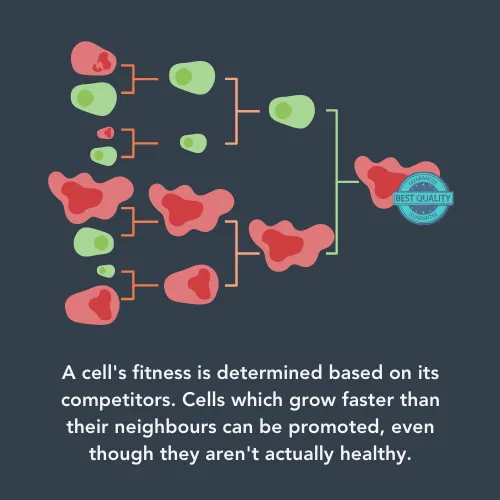

Who wins that competition depends on the type of errors the cancer cell has, and whether that makes the cell seem more or less fit. You would probably think that all cancer cells are less fit – after all, they don’t follow the rules and aren’t serving a proper purpose.

However, cells can only figure out fitness compared to other nearby cells – even an unfit cell, if surrounded by other unfit cells, would be allowed to survive. It’s also important to remember that our cells struggle to recognise cancer cells because they were once healthy cells. Therefore, they might just see a cell that is growing fast and reproducing quickly and class it as ‘super fit’.

Therefore, the cancer cell’s survival can depend how fit the cells around it are and then whether, based on the complicated hierarchy of genetics, the cancer cell is better than these neighbouring cells. For example, if the cancer cell has errors that allow it to grow and divide faster than healthy cells, it may be allowed to grow and spread at the expense of any seemingly ‘less fit’ healthy cells.

Cancer cells also have an added advantage – they can ignore signals that tell them to die. All cells have genes built in which tell them to die when they are unhealthy, old, or no longer needed. However, cancer cells often have errors in these genes, meaning they might not receive the signal or have the means to act on it. Alongside cell competition, this helps cancer cells survive despite their issues.

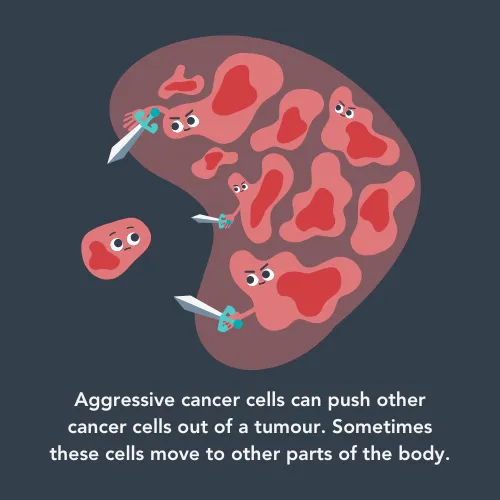

Variation between cancer cells within a tumour could also lead to competition, resulting in the more aggressive cancer cells taking over the tumour. However, less fit cancer cells aren’t always killed – sometimes they’re just pushed out of the tumour to fend for themselves. Recent research suggests that these cells, whilst not as aggressive as their competitors, can sometimes find a new home elsewhere in the body, causing new tumours.

Why it matters

Whilst the first evidence of cell competition was discovered by PhD students in 1973, the first conference on this phenomenon only just took place in February 2019. There’s a lot that researchers don’t understand yet and a lot to discover, which makes this an exciting field of research.

It seems that there aren’t really any simple answers when it comes to cell competition. This is especially true in relation to cancer. Most of the research for this blog focused mostly on adult cancer, so it would be intriguing to learn whether cells compete in the same way in childhood cancer, and whether the rules for determining cell fitness are the same. Could there be a way to take advantage of cell competition as a treatment strategy? We won’t find out without more research from the legions of committed scientists who are working hard to create a better future for children with cancer.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG