Sometimes, processes that we see in the world also apply to cancer, like evolution. Just like with animals, if a cancer cell is very good at surviving, then it is more likely spread. Over time, this can lead to cancer being able to resist treatment or grow back after treatment.

The key thing required for evolution is diversity – there have to be differences between cancer cells in how they survive, respond to treatment, or behave. This variability can help cancer cells survive and adapt, but it also makes doctors jobs much harder. Cancer can be a lot less predictable when there’s lots of diversity, and this makes it harder to treat.

A very variable cancer

Neuroblastoma is a type of childhood cancer that grows from early types of nerve cells, affecting mostly children under five years old. It is known to have lots of ‘clinical variability’, meaning that it can be very different between patients, and using the same treatment can produce completely different results. The cancer cells might have different genetics, different proteins inside, and even may have grown from different types of cells. Then, there is the added challenge of evolution – how the diverse group of neuroblastoma cells vary over time, for example becoming resistant to treatment.

This may make it really difficult to treat some high-risk cancer types, and also to develop treatments for them, as there are so many variations. Even if doctors had a way of knowing everything about the cancer cells, they may not be able to find research that showed them how their young patient would react to a certain treatment.

Research to improve outcomes

Working at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, Dr Alejandra Bruna has a plan to uncover exactly how neuroblastoma cells change over time.

Dr Alejandra Bruna

She believes that cancer cells have a trait called ‘phenotypic plasticity’. This means that they can change how they look or behave in response to external factors, like cancer treatments, without having physical changes in their DNA sequence to cope with each different situation.

Phenotypic plasticity can lead to changes in the way a cell can read and use their genetic code, which can help them survive treatments.

A cell’s response to a situation, such as responding to chemotherapy by becoming resistant to that treatment, isn’t part of the genetic code. However, Alejandra’s current work is based on the idea that there is a way for cancer cells to pass on their ability to respond in a variety of ways. Cancer cells which are more able to respond effectively are more likely to survive, and so the adaptation which allows the cell to respond in lots of different ways gets more and more common. This means that there will be more and more cancer cells that are not only resistant to a treatment, but have the ability to become resistant to any future treatments too.

Currently, Alejandra’s team don’t know whether the adaptation for phenotypic plasticity is passed on through changes to the DNA sequence, or through a process called ‘epigenetic memory’. This is a natural process where molecules attach to different places on the DNA strand, turning genes on or off. When a cancer cell divides, its DNA is copied to create new cells. During this process, these epigenetic molecules are copied as well. So, if a gene was turned off by one of these molecules in one cell, that same change will be copied and passed on to the new cells.

Because neuroblastoma cells can come from different types of healthy cell, they can all have different DNA sequences to start with. Alejandra believes that the addition of phenotypic plasticity to that can explain how so many variants of neuroblastoma arise.

She said: "Neuroblastoma tumours are made of different cells. I think you could use the analogy of a community or a village made of cells – they have distinctive functions but all work together to promote their survival and adapt to external and internal changes.

Having different cells with different genetics, and ways of using their genetic codes, is an evolutionary advantage for cancer. The more diversity, the more likely that one of these cells will, by chance, already be a little bit more able to survive treatment.

"In addition, this variability can be acquired by cancer cells. This means that a change in their environment will cause changes in these cells to protect them, similar to how we get tanned when we are exposed to the sun or have a temperature when exposed to a virus."

Understanding the effect of evolution

In her project, funded by The Little Princess Trust in partnership with CCLG, she is working on models of neuroblastoma that are created from real patient’s cancer samples. These models will mimic a patient’s cancer throughout the cancer journey, from diagnosis to relapse. This will let Alejandra and her team look at the impact of different cancer cell variations on treatment response and disease progression.

She said: "There is evidence that relapsed neuroblastoma cell genetics can be different to the initial tumour, which suggests that cancer cells can evolve like animals do, where the fittest cells survive and spread. However, this is not always the case.

"We are currently investigating phenotypic diversity, mainly based on biological properties such as proliferation, the expression of cell surface markers and the ability to self-renew. To provide evidence that this phenotypic diversity is fundamental for neuroblastoma cancer cells to evolve, and identify whether plasticity is responsible for such diversity, we are using single cell tagging approaches linked to multi parametric sequencing platforms.

"These initial studies will help pave the way toward the identification of biomarkers of plasticity, which could be used as prognosis markers and/or to derived new treatment strategies to block evolution."

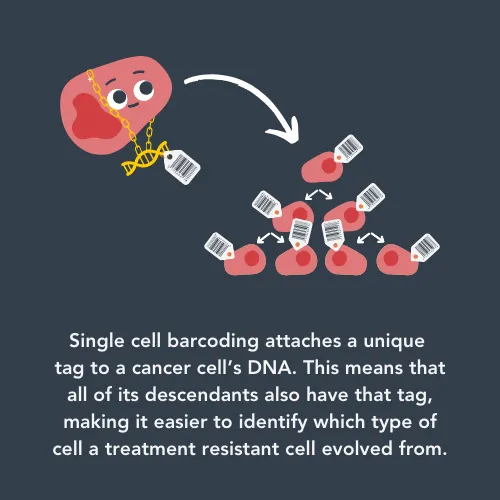

Alejandra is using a cutting-edge technique called single-cell barcoding. This is a way of inserting a unique DNA sequence into a neuroblastoma cell so that all of the cells have a unique identifier which can be traced. The research team can then look at the cells phenotypic behaviour over time and study how they evolved with treatment.

She said: "We are really excited about the innovative technology we are using to track and trace cells within an evolving tumour. It will open the door to the new discoveries and new ideas needed to better understand how cancer cells adapt to treatment, resist treatment and regrow. This is vital because treatment options are scarce for relapsed neuroblastoma and the outcomes are dismal. The use of these approaches which include single cell sequencing technologies, allows us to look at the unexplored territories of tumour evolution at an unprecedented level."

This project has another year to go, which is when all of the results will come together to form a coherent picture of the evolution of neuroblastoma.

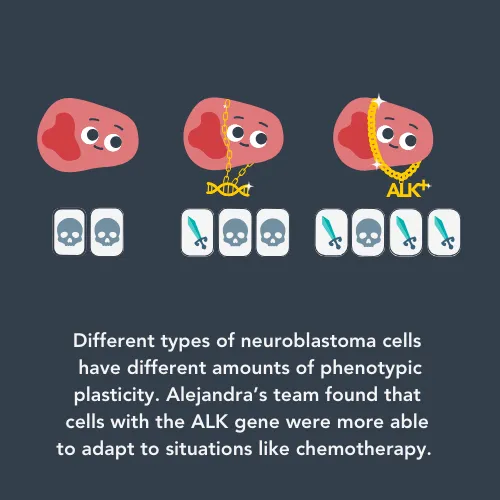

So far, the researchers have found that neuroblastoma cells have an innate ability to adapt to their surroundings in a cancer subtype- and treatment-specific manner. The amount that the cancer cell can vary without DNA changes can depend on what type the initial neuroblastoma cell was. Therefore, knowing what type of cell the neuroblastoma first came from could help researchers predict treatment response.

One interesting finding is related to a genetic mutation that some neuroblastoma cells have in a gene called ALK. The ALK gene is supposed to be turned off before a child is born, but in some cancers it fuses with other genes and turns itself on.

Alejandra’s team found that ALK+ neuroblastoma cells are a lot better at adapting to different situations than cells without the ALK gene. The higher amount of phenotypic plasticity could explain why some patients with ALK+ neuroblastoma relapse, even after being given chemotherapy that is designed to turn the ALK gene off. Alejandra will continue working on this, and hopes to find ways to identify patients whose cancer will progress and new treatment strategies to help them.

Helping patients

Part of this project’s final aim is to investigate different combinations of existing neuroblastoma treatments to target the cells that are driving treatment resistance and relapse. Alejandra’s team will analyse the data from tracking the evolution of neuroblastoma and integrate it with high-throughput drug screening and specialist computer programmes to predict potential treatments, based on the specific changes that are contributing to relapse. This could be a completely new way to treat neuroblastoma.

If this project is successful, Alejandra and her team hope to conduct similar research into other types of cancer.

She said:

Our immediate next step is to identify our new non-genetic markers of phenotypic plasticity in patients and see if we can link these markers with prognosis and outcome. We eventually hope to translate our discoveries into smarter and kinder treatment options and strategies for children with cancer to improve their chance of survival and quality of life.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG