A tumour in the brain can begin in the brain itself (primary) or from another part of the body (secondary). This information is about primary brain tumours.

The brain sits within the skull and is part of the central nervous system which includes the spinal cord. The brain and the spinal cord are bathed in a liquid called the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and are surrounded by three layers of membrane.

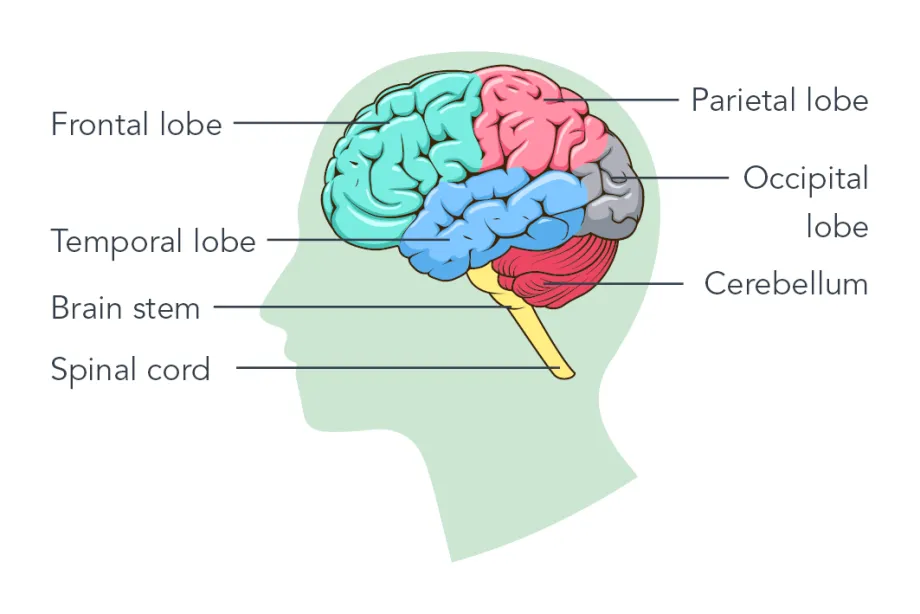

The main parts of the brain are:

- Cerebrum - the largest part of the brain and at the top of the head. It is made up of two halves (hemispheres) and is divided into lobes - the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital, as shown on the diagram. It controls thinking, learning, memory, problem solving, emotions and touch. It also helps us be aware of our body position.

- Cerebellum - the back part of the brain and controls movement, balance and coordination.

- Brain stem - connects the brain to the spinal cord. It is in the lower part of the brain just above the neck. It controls breathing, body temperature, heart rate and blood pressure, eye movements and swallowing.

These will depend on the size of the tumour, where it is and how it affects that part of the brain. A growing tumour may push the brain out of the way or block the flow of fluid in the brain. Some symptoms are caused by the pressure inside the head (intracranial pressure) being higher than it should be. Brain tumours may also cause problems with balance and walking, weakness on one side of the body, or changes in behaviour.

Some common symptoms can include:

- headaches (often worse in the morning)

- being sick (usually in the morning) or feeling sick

- fits (seizures)

- feeling irritated or disinterested in day-to-day things

- abnormal eye movements, blurring or double vision

- feeling very tired quicker than usual

- feeling extremely sleepy (drowsy) for no reason

Some of these are common even without a brain tumour, and this can cause difficulties with diagnosis.

A variety of tests and investigations may be needed to diagnose a brain tumour. Any tests and investigations that your child needs will be explained to you. Your child’s doctor will ask about the problems your child has had recently. They may look into the back of your child’s eyes to check for swelling, which can be a sign of raised pressure in the brain. They will usually check things like balance, coordination, sensation and reflexes. They will then arrange for further tests as below:

CT or MRI scans

Ordinary x-rays are not usually helpful for brain tumours. Most children will have a CT or an MRI scan, which looks in detail at the inside of the brain. A CT scan is quick but uses a lot of x-rays, so it is important to avoid using this too much. An MRI scan gives more detailed pictures, but takes much longer. Machines are noisy, and children may need an anaesthetic to help them stay still.

Blood tests

These are usually done to make sure it is safe to do an operation, and can also be used to help diagnose certain types of tumours.

Biopsy

A small operation is done (under anaesthetic) to remove a piece of the tumour. The sample is looked at in the laboratory to find out exactly what type of tumour it is. A biopsy isn’t always done as it is sometimes better to remove the whole tumour in one operation. In this case, it will be a few days before the exact type of tumour is known. Occasionally, because of the position in the brain and what the scan pictures show, your child’s doctor may start treatment without a biopsy or surgery.

Eye tests

These are useful as part of diagnosis and also for monitoring response to treatment. Tests will look at how well your child can see, including any double-vision, eye movements and blind spots.

There are different types of brain tumours and they are usually named after the type of cells they develop from. The main types are astrocytoma, ependymoma, and medulloblastoma, but there are many other, less common types. Brain tumours can be non-cancerous (benign) or cancerous (malignant).

Non-cancerous brain tumours

It is unusual for benign brain tumour cells to spread into other areas. However, they can have serious effects if they continue to grow, so it is still important to take an active approach to treatment. Sometimes, it may be difficult to remove a benign tumour, because of where it is, so other treatments may be needed.

The most common benign brain tumours are low-grade astrocytoma (also called low-grade glioma) and craniopharyngioma.

Cancerous primary brain tumours

Malignant primary brain tumours are most likely to cause problems by causing pressure and damage to the areas around them and by spreading to the normal brain tissue close by. Sometimes, they spread to other areas distant to the original tumour.

The main types of malignant tumours that affect children are high-grade gliomas, ependymomas and medulloblastomas.

Medulloblastomas are the most common malignant brain tumours found in children. They usually develop in the back of the brain (cerebellum). They may spread to other parts of the brain or into the spinal cord, and treatment must include the whole of the central nervous system.

Treatment will depend on the type of brain tumour, its size and where it is in the brain. Surgery, radiotherapy and drugs are used to treat brain tumours. Your child may have one treatment or a combination of treatments.

Surgery

Usually, a specialist surgeon will operate to remove as much of the tumour as possible. Operations can be long and often last more than six to eight hours.

Sometimes, the fluid in and around the brain does not flow freely, as a result of the tumour or brain swelling. In this case, it may be necessary to place a fine tube (shunt) to drain excess fluid from the brain and into the lining of the tummy area (abdomen). You cannot see the shunt outside of the body. Another way of treating this is to create a drainage route for the fluid to bypass the obstruction.

After the operation, your child may spend some time in an intensive care ward or high dependency unit, so nurses and doctors can keep a close eye on them.

Once the type of tumour is known, a plan to treat any tumour left behind can be made. For benign tumours, no further treatment may be needed.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy treats cancer by using high-energy radiation beams to destroy cancer cells whilst doing as little harm as possible to normal cells.

Radiotherapy is delivered carefully and accurately, and lots of preparation is required before treatment can start. Radiotherapy is given in a number of daily treatments (or fractions) for up to six weeks. Each treatment usually takes only a few minutes.

Sometimes more specialised types of radiotherapy may be used. Your child’s doctor will explain more about this.

Drug treatments

These include chemotherapy and targeted drugs. Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer drugs to destroy cancer cells. The combination of drugs and the length of treatment will depend on your child’s particular type of tumour.

Other medicines

Your child may need to take medicines for a while to reduce or control the symptoms of the brain tumour:

- steroids – reduce swelling and inflammation in the brain and can help with symptoms.

- anticonvulsants – help prevent fits, which can be a problem before or after operations on the brain. They may only be necessary for a short period.

Clinical trials

Many children have their treatment as part of a clinical research trial. Clinical trials are carried out to try to improve our understanding of the best way to treat an illness, usually by comparing the standard treatment with a new or modified version. Clinical trials mean there are now better results for curing children’s cancers compared with just a few years ago.

Your child’s medical team will talk to you about taking part in a clinical trial and will answer any questions you have. Taking part in a research trial is completely voluntary, and you’ll be given plenty of time to decide if it’s right for your child. You may decide not to take part, or you can withdraw from a trial at any stage. You will then receive the best standard treatment available.

Ependymoma II trial

CCLG has made a video about one family’s experience of deciding whether their child should take part in a trial or not. This video is about the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) ependymoma II trial. Thank you to Max’s family for taking part.

National treatment guidelines

Sometimes, clinical trials are not available for your child’s tumour. In these cases, your doctors will offer the most appropriate treatment, using guidelines which have been agreed by experts across the UK. Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) is an important organisation which helps to produce these guidelines.

This video was filmed and developed by CCLG © 2024

International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) ependymoma II trial

Once treatment has finished, the doctors will monitor your child closely with regular appointments to be sure that the cancer has not come back and there are no complications. After a while, you will not need to visit the clinic so often. If you have specific concerns about your child’s condition and treatment, it’s best to discuss them with your child’s doctor, who knows the situation in detail.

This information is about brain tumours in children, aged 0-14 years.

This information is about brain tumours in children, aged 0-14 years. You can find out more about brain tumours in teenages and young adults (aged 15-24) on our 'Brain tumours in teenagers and young adults' page.

Further resources

Better Safe Than Tumour

National awareness campaigns of symptoms of brain tumours in children and young people

The Brain Tumour Charity

Offers information and support to families, and a helpline for people living with, or affected by, brain tumours. FREE helpline: 0808 800 0004.

Brain and Spine Foundation

Support for anyone affected by neurological issues FREE helpline: 0808 808 1000

Brainbow

Rehabilitation service at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge for children based in the East of England

Child Brain Injury Trust

Information on children’s acquired brain injury and training and support for professionals including school staff FREE helpline: 0303 303 2248

Children's Brain Tumour Research Centre

Brings together leading healthcare professionals and researchers who are experts in their fields, and are all committed to improving our understanding of childhood brain tumours

The Children’s Trust Brain Injury Hub

Information and advice for families about acquired brain injury. Offers rehabilitation and education services.

The International Brain Tumour Alliance

Global network for brain tumour patient and carer groups around the world

Posterior fossa syndrome factsheet

(published by CCLG, 2025)

Resources for education

Returning to school: A teacher's guide for pupils with brain tumours, during and after treatment

(published by the Royal Marsden, 2019)

A school’s guide to supporting a pupil with cancer

(published by CCLG, 2023)

Resources for young children

Zarah Has a Brain Tumour (Young Lives vs Cancer)

Zarah Has a Brain Tumour is a story for children who have a brain tumour to read with their families. The story follows eight-year-old Zarah through her cancer diagnosis and treatment. Using bright, colourful illustrations by Allen Fatimaharan, the book helps children to understand cancer and know what to expect. It’s designed for children aged seven to 11, but might also be helpful for others who are looking for information about brain tumours and treatment that’s easy to understand.

Meet Jake (Brain Tumour Charity)

Jake is an animated 8-year-old boy who helps children with a brain tumour get answers to some of their questions. His videos provide simple and easy to understand information about life with a diagnosis, so they’re great for grown ups too.